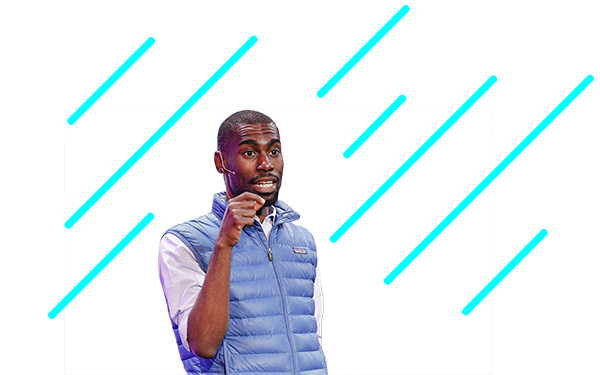

The 74 Interview: DeRay Mckesson, Baltimore Mayoral Candidate and Black Lives Matter Leader

See previous 74 interviews: Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, Newark superintendent Cami Anderson, L.A. mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. (See the complete archive)

Updated April 28, 2016

DeRay McKesson came in sixth in the Democratic primary, earning about 3,000 votes of the roughly 125,000 cast. He said on Twitter the day after the election that he is "not sure what comes next."

(Baltimore) — DeRay Mckesson, activist, educator, and now candidate for mayor of his native Baltimore, rose to prominence in the wake of the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown, raising consciousness about issues of race and injustice on Twitter and working to reform police practices and the criminal justice system.

That work, he said, doesn’t really change when the goal shifts to improving schools and educational outcomes for all of the country’s children.

“Protest at its root is about telling the truth in public,” he said. “That commitment doesn’t change. The context changes, but the commitment doesn’t. The truth is that there are systems and structures that are not equitable, that are not just, but can be, and that’s our work.”

His own childhood was rocky. Both of his parents were addicted to drugs, he said, and his mother left the family when Mckesson was three. He moved around a lot, spending his early elementary years in the Baltimore City Schools before moving to a Catholic school for a few years and finishing out his schooling in Baltimore County public schools.

There’s a “host of things” that have to be done to make things more just and equitable for all kids, Mckesson said, but he’s particularly focused on the years before a child enters the K-12 system.

He’s a big fan of voluntary home visiting programs. A trained professional, usually a nurse or social worker, visits first-time, low-income parents, often when a woman is pregnant, to help with everything from child-rearing advice to health screenings to connections with other social services.

“There’s so many parents who have a whole lot of love, but they just don’t know [how to parent.] What do you do if there’s not somebody there to teach you? The whole city benefits from parents having skills, especially early,” he said.

The programs have a wide array of supporters, from early learning advocates to law enforcement. Studies of some of the best-designed programs show gains in test scores, reduced childhood injuries and emergency room visits, less reliance among participating families on welfare programs and other desirable outcomes that also save taxpayers money long term. But they aren’t well known and in many places, demand outpaces supply.

“What is so frustrating about this stuff is we know the answer. It’s not a question of what the answers are. We know them. It’s a question of what’s the commitment,” he said.

If he prevails in a crowded field of Democrats, Mckesson, 30, pledges that in his first 100 days as mayor he would expand Baltimore’s pre-K program to enroll all low-income 3- and 4-year-olds. About 85 percent of that group are already enrolled, he said, but there are about 500 to 600 young children who should be in programs but aren’t.

(Related The 74: Baltimore’s Next Mayor: 13 Democrats Who Want the Job, and What School Challenges Await Them)

One of the problems in Baltimore, he said, is that parents are unwilling to enroll children outside of a neighborhood school if local options are full, and they don’t like to use public transportation to get kids to preschool.

Maryland law requires schools to offer preschool but doesn’t fund it, Mckesson said. “The city and the school system need to press forward for dedicated funding, even if it’s from philanthropic partners or private industry, while we work to fix the formula,” he said.

He’s also focused on what happens to folks after they leave Baltimore’s public schools. About 40 percent of the city’s adult population is not functionally literate, he said. (Good statistics on adult illiteracy are hard to come by, but 16 percent of adults in Baltimore lacked “basic prose literacy skills” in 2003, according to federal statistics. That was down from 24 percent in 1992.)

“Literally, this is not working,” he said of the lack of a broad literacy strategy or easily accessible resources for adult learners. People are taking the GED and not passing, he said, or they’re studying at community colleges with dismal graduation rates. The graduation rate at Baltimore City Community College is 5 percent.

“The focus on K-12 at best might hold us steady, but it won’t address the generation of people who are not functional,” he said. “So we think about the bookends, making sure there’s a strategy for those, because those are the pieces that often get left behind only because there’s a whole apparatus for K-12.”

That’s not to say, of course, that he doesn’t care about K-12.

After college at Bowdoin, a selective liberal arts school in Maine, he joined Teach for America and taught sixth grade math in New York City, during which time he was also a United Federation of Teachers chapter leader.

His education career has been the wellspring for some of the weird rumors that have circulated since he launched his campaign in early February: that he’s funded by the Illuminati (a secret cult of the rich and powerful) or billionaire liberal George Soros or outerwear maker Patagonia (manufacturer of his ever-present blue puffy vest), that he’s a TFA plant, and that he wants to privatize public schools.

“TFA is an imperfect organization, blah blah blah, but the reality is that my entire education career is not reduced to any one experience,” he said. (He’s also worked at the Harlem Children’s Zone, opened an after-school program in Baltimore for middle-schoolers, and worked in the human capital departments of both the Baltimore City and Minneapolis schools.) “I did all those things, and no one was like THE thing.”

In reality, he thinks that Baltimore’s current charter system, with the city schools as authorizer and unionized teachers, is a good model.

And he’s not a fan of mayoral control, at least the idea that it’s some sort of end-all savior for floundering urban schools. In Baltimore, the mayor and governor jointly select the city’s school board that then appoints the superintendent who controls day-to-day operations. Other candidates have said they’ll go to the state legislature to change the law and give the mayor greater control.

“There are some places where there is mayoral control and it works, there are some places where it doesn’t. In and of itself, it is not the solution. I’m trying to figure out what’s right for kids,” he said. “People are up here fighting about mayoral control today, that’s not going to change a kid’s life.”

That view — what’s good for kids, what’s going to change lives today — is what led him to quit his job in Minneapolis, launching his arrival in the public consciousness and ultimately mayoral politics.

“I’m a national expert on human capital in school systems, that was my thing. But Mike Brown will never know a college professor. Tamir Rice will never know a high school teacher,” he said, referring to the 18-year-old Missouri high school graduate killed by police and the 12-year-old boy from Cleveland who was shot and killed by cops the same year. Their deaths ignited the Black Lives Matter movement.

(Related The 74: A Year After Ferguson, St. Louis Parents Fight to Escape Michael Brown’s Terrible High School)

“My work shifted,” Mckesson added. “Now I’m interested in what role can I be in to put in place the concrete things that will change people’s lives.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)