The $40 Million Question Now Looming Over New Jersey’s Top Teachers Union

Commentary: Will the New Jersey Education Association learn from its president’s failed gubernatorial run?

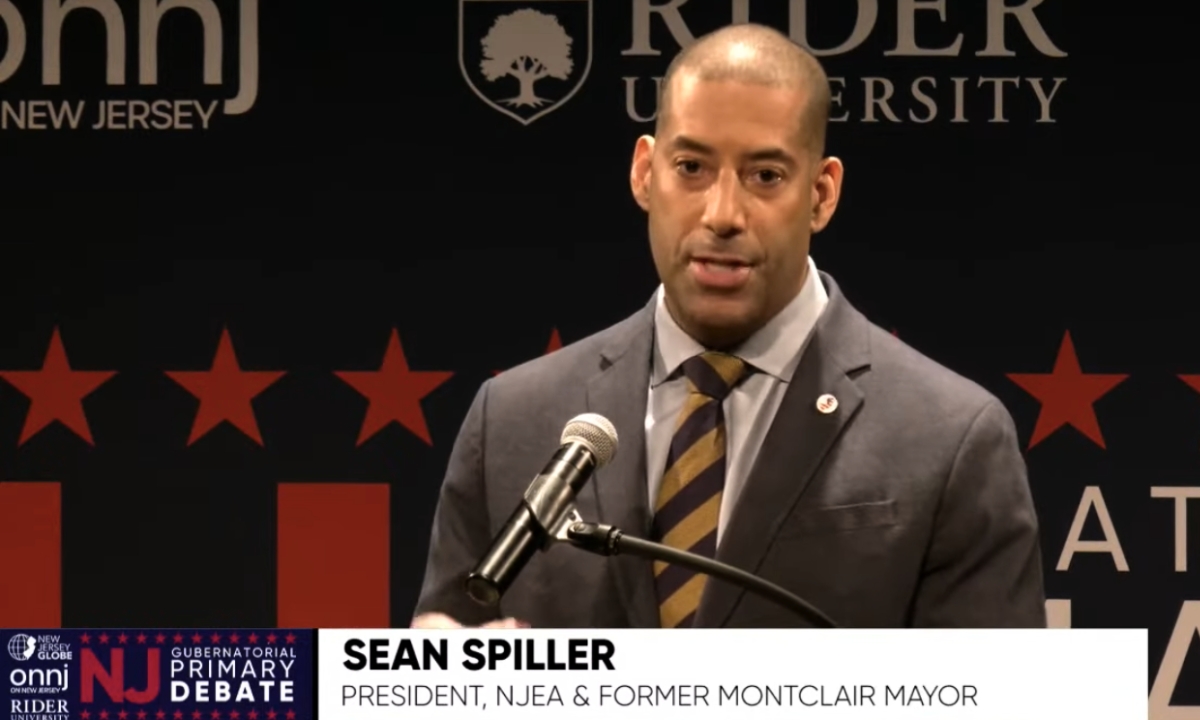

“Spiller makes strong showing in Dem primary.” So reads the title of the June 10 statement released by the New Jersey Education Association, reflecting on the gubernatorial campaign of its president, Sean Spiller. “NJEA President Sean Spiller finished out of the lead in today’s Democratic primary for governor,” the statement continues. While expressing disappointment that Spiller failed to fend off his primary challengers, the union was nevertheless upbeat: “A relentless yearlong campaign focused on what New Jersey voters care about paid off with a strong showing that makes it clear that educators and working people have a place in New Jersey politics.”

One could be forgiven if, upon reading the above, one thought that Spiller finished a close second or third in the Democratic primary — that he ran a strong campaign, connected with voters in New Jersey, parried attacks from a hostile press, and fought valiantly against his opponents, only to lose by a handful of votes.

But that isn’t remotely what happened.

Spiller finished fifth, earning less than 11 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, the winner, Rep. Mikie Sherrill, raked in 34 percent. And that was despite the union, through a combination of super PACs and independent expenditure organizations, spending north of $40 million to elect Spiller — about twice the amount spent by the second-highest-spending candidate in the race.

How did the largest teacher’s union in New Jersey take tens of millions of dollars of their members’ dues and essentially light them on fire in an abortive attempt to get its own president crowned as the Democratic candidate for governor? A number of explanations are possible, but one seems most compelling: simple incompetence. The more urgent question now is whether the union will learn from its mistakes — or whether it will continue to suffer in political obscurity.

It’s important to note the scale of NJEA’s failure. Politico reports that “no other special interest group has ever spent as much in state history to promote a single candidate” as the NJEA did with Spiller. The NJEA spent about $8 million more in one primary race in one state than the National Education Association, NJEA’s parent organization, spent at the national level between 2023 and 2024. (Spiller’s poor showing is a good reminder that it takes more than money to win an election — even in a post-Citizens United world.)

Another concerning stat: A lack of union turnout. The NJEA boasts around 200,000 members, yet Spiller received less than 90,000 votes total. Some back-of-the-envelope math suggests that, even if all of Spiller’s votes came from union members (a dubious assumption), he would have received fewer than half of their votes. John Napolitani, a local mayor and head of the teachers’ union in Asbury Park, summed it up for Politico: “I think it was a very poorly calculated and piss-poor decision by the NJEA to blow that kind of money.”

Indeed, Spiller seems to have been a uniquely bad candidate in this race. The proof is in Spiller’s fifth-place showing in his hometown of Montclair, where he was mayor from 2020-2024 (including during a period of union-induced extended school closures). But this poor showing should not have necessarily been a surprise: In Montclair, Spiller was embroiled in a scandal involving potential health-insurance fraud, during which he suspiciously invoked his Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination over 400 times. (Spiller announced his intention to not run for a second term as mayor shortly after the transcript of his deposition became public.) If voters in your hometown reject you so thoroughly, then you’re probably not a great candidate in a statewide race.

It could also be the case that Spiller, as the public face of the largest teacher’s union in New Jersey, was a painful reminder of extended COVID-19 school closures in 2020-21. Indeed, the NJEA (of which Spiller was then the vice president) pushed back against Gov. Phil Murphy’s November 2020 call for schools across the state to return to in-person instruction. At the time, one poll found that less than half of New Jersey parents were satisfied with virtual instruction. Today, almost nobody seems willing to defend the extended school closures during the pandemic, especially considering the growing body of evidence showing that the more time students spent outside of the classroom, the more they fell behind academically.

Five years after the pandemic, the NJEA might hope that New Jersey voters would have forgotten the school closures, or at least forgiven the union for them. But parents may have a longer memory of being locked out of classrooms while nearly every other school in America was back in session.

Still, even if unpopular with New Jersey parents, the NJEA could have spent its money more wisely by supporting a candidate other than Spiller. A competent organization seeking to have a tangible political impact considers a variety of candidates, weighs their strengths and weaknesses, and supports the one it deems most likely to win the race. If the union had conducted such a process, it would have surely rejected Spiller outright, especially considering its knowledge of Spiller’s rocky mayoral tenure in Montclair. But instead, the NJEA funneled $40 million of teacher dues toward a candidate who earned a fifth-place finish in a gubernatorial primary.

A competent organization also learns from its failures. Which raises the question: What will the NJEA learn from its failure here? Will its leaders look carefully at the decisions they made so they can avoid a similar fate in the future, or will they bury their heads in the sand as they face uncomfortable headlines and inquiries from their members?

In the long term, it’s deeper questions about influence and efficacy that may haunt them, such as: Can the NJEA still connect with voters? Will its leadership continue to waste tens of millions of union dues on long-shot primary campaigns? Is the largest teachers union in a deep-blue state like New Jersey losing political clout?

Judging by the semi-triumphant tone of the statement released after Spiller’s resounding defeat, it seems that current NJEA leadership sees little to be concerned about. But refusing to take ownership of such a colossal defeat will likely only make things worse for NJEA and its members.

If the union has any hope of remaining politically relevant in New Jersey, then it must treat the Spiller campaign — and collapse — as a $40 million wake-up call.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)