New York, New York

Sobella Quezada remembers the jittery anticipation that fluttered through her teenage self 14 years ago during an unusual car ride from the Bronx to Albany. She was en route to meet Gov. George Pataki.

Her eighth-grade English teacher, Nick Marinacci, a Teach for America educator, recommended her for a student leadership and engagement award and she had been selected as the student representative from the Bronx.

Her father, a Dominican cab driver, dressed up in a suit and drove Quezada and her younger brother the two-and-a-half hours up the New York state Thruway in his yellow cab. At the ceremony, Quezada shook the governor’s hand and was given a laptop — a serious luxury for a middle school kid from her working-class neighborhood in 2001.

For Quezada, the oldest daughter of immigrant parents, that small moment of public recognition for her achievements served to broaden her own expectations for her future.

“That was probably one of the most special moments in my life,” she said on a recent afternoon near her school.

Marinacci’s impact on her education went further. He encouraged her and some classmates to apply to Catholic high school, which she ultimately attended rather than the struggling, violence-plagued public school in her neighborhood.

He introduced her to Shakespeare, and she went on to major in English literature. And, in a school where a four-year degree was for many students nothing more than “a vague possibility,” Quezada said, he emphasized the value of a college education.

“He spoke to us about it as if that’s what you do after high school,” Quezada said. “He kind of instilled that expectation as opposed to making it seem like an option.”

Now 28, Quezada is three months into her own two-year commitment with Teach for America, a highly selective program that takes graduates from the country’s top colleges and trains them to teach in low-performing urban and rural schools. As it marks its 25th anniversary and confronts pressures both internal and external, TFA sees “second-generation” corps member like Quezada, who credit their involvement to a standout TFA teacher from their youth, as a source of hope.

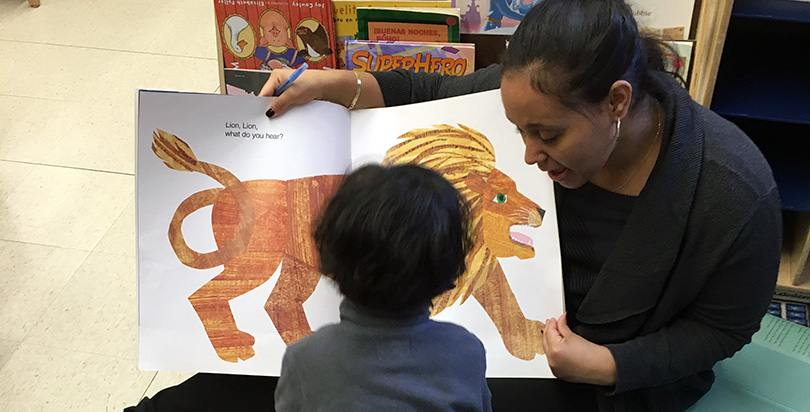

Quezada works as a lead teacher at the Head Start program at P.S. 152, the Dyckman Valley school, in Manhattan. Walking into her classroom in Washington Heights on many mornings, she feels a similar sense of anticipation about the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead as she did that morning driving to meet the governor. In this case, it’s helping 15 economically disadvantaged 3- and 4-year-olds, many with special needs, reach their learning and developmental milestones.

She left a relatively cushy yet unfulfilling job as a Social Security claims representative to apply to TFA for a second time — her first attempt was as a senior in college — and this time got in.

“Had I gotten in at 23, I would not have had that perspective (from four years working in another industry),” she said. “I feel like I’m living my purpose.”

TFA produces 4,000 to 5,000 alumni annually and expects to top 50,000 alumni next year. About 140 of this year’s 4,100 new recruits report that they were once taught by corps members themselves, among an estimated 500 total with that connection.

In New York City, almost 1 in 10 new recruits this year are second generation, Communications and Marketing Director Katie Ware said.

It’s not totally a coincidence.

As TFA grows, the organization is revamping its recruiting strategy in response to criticism about the preparedness and diversity of its members, as well as high turnover. Frequently, new recruits are inexperienced teachers who simultaneously earn teaching certificates while working full-time in schools across the country that partner with TFA, including traditional public schools and charter schools.

In New York City, TFA is doubling down on asking alumni and the school leaders they work for to reach out to their former students about joining the corps, Ware said.

“As we’re recruiting more and more from the neighborhoods we serve, the likelihood of someone being a ‘second-generation corps member’ is certainly increasing — whether they know it or not,” she said in an email.

In Jessica Pena’s case, reconnecting with her former TFA teacher-turned-mentor was a deliberate step as she considered signing up for a two-year commitment.

“In college, I knew I wanted to be a teacher, but didn’t know which path I wanted to take to get there,” she said.

She tracked down her seventh-grade science teacher, Anu Malipatil, and they began emailing. Malipatil walked her through the ins-and-outs of applying, completing a master’s degree and what type of salary and benefits she could expect. Mostly, they talked about the biggest question — why do it?

Pictured: Jessica Pena | Above: Sobella Quezada, a 2015 Teach for America corps member, reads to a student in her Head Start class at P.S. 152, the Dyckman Valley school, in Manhattan. The community school is run by the Children's Aid Society, a New York charity that serves children living in poverty. (Courtesy photos)

Over a two-hour dinner, Pena described for Malipatil her emotional, eye-opening experience at a small, mostly white liberal arts college in California, where she struggled to make friends with her privileged classmates and was stung by racism and sexism.

“That really pushed me to come back to my community and want to talk to my community about (diversity),” Pena said.

After completing the summer training intensive, the 23-year-old is now a social studies teacher at the Bronx Claremont International School, not too far from where she grew up.

Malipatil is currently the education director at the Overdeck Family Foundation, which seeks to help children achieve their academic potential by funding programs with proven impact. She taught in the New York City corps for two years and then joined the administration, where she led curriculum development and staff retention efforts between 2006 and 2010. She also volunteers with TFA’s Young Professionals Committee, part of the organization’s fundraising arm, as a development coach.

In the years since she left, Malipatil said she’s watched TFA struggle through a major round of internal layoffs and flagging recruitment numbers. Equal distribution of talent and financial resources from region to region has also been a problem, she said.

“This is an important inflection period and time for them to think about how they’re going to stay relevant in sort of a dynamic and changing system and time,” Malipatil said. “I think the next two years are going to be a big transition period for them.”

Several scathing dispatches from disenchanted alumni have circulated widely online, adding fuel to the fire, and teachers unions have sounded off on the organization’s close ties to charter schools. Many TFA critics view it as contributing to what they allege is the dismantling of public schools.

Others have confirmed their commitment to the organization’s values (Read an essay at The Seventy Four by a member of Colby College’s Class of 2016 on why she’s joining TFA). David Gergen, a TFA leadership team member and advisor to four U.S. presidents, lamented college campus protests meant to dissuade students from joining a group trying to make a difference in some of the country’s most disadvantaged schools. Gergen made his remarks at a September education conference at Harvard University where he is the director of the Center for Public Leadership.

But as the organization moves into its next phase, staff morale appears to be rebounding and TFA has much to be proud of, Malipatil said.

She pointed to alumni like former Tennessee state Education Commissioner Kevin Huffman and Louisiana State Superintendent of Education John White, who have evolved into champions for education reform. (Huffman is a contributor to The Seventy Four.)

TFA’s leadership transition — co-CEO Matt Kramer announced in September he is stepping down — is also an opportunity to address some of the divisiveness that has surrounded it in recent years.

Elisa Villanueva Beard, co-CEO since 2013, is now leading the organization solo.

“I think Elisa has the sensibility and the experience and the connections to communities to do that in a more holistic and integrated way” as TFA moves forward, Malipatil said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)