Texas Kids Denied Special Ed Supports 52% Less Likely to Graduate From HS, 38% Less Likely to Go to College, Shocking New Study Finds

Students with mild to moderate learning impairment who lose special education services are 52 percent less likely to graduate from high school and 38 percent less likely to enroll in college than students who remain in special ed, according to recently released, first-of-its-kind research by two doctoral candidates in economics.

Likely because their families lacked the resources to mitigate the loss of services at school, low-income students of color and students in impoverished districts bore the brunt of the losses, reported Briana Ballis and Katelyn Heath, researchers at the University of California, Davis, and Cornell University, respectively.

“I wasn’t particularly surprised that the effects would be negative, but by the extent to which this is leading to much lower educational attainment,” Ballis told The 74. “Special education is very costly, but the cost of having someone who doesn’t graduate high school or enroll in college is also very high.”

The study examined a Texas policy, quietly implemented in 2004, that imposed an 8.5 percent cap on the number of special ed students in every district in the state. A scandal erupted in 2016 when the Houston Chronicle revealed the existence of the cap — which was far below the state’s 11.6 percent special ed enrollment when it was put in place — and the U.S. Department of Education launched an investigation. In January 2018, the feds ordered Texas to revamp its special education system and begin complying with a mandate under the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act to seek out and evaluate all children who might need support in schools.

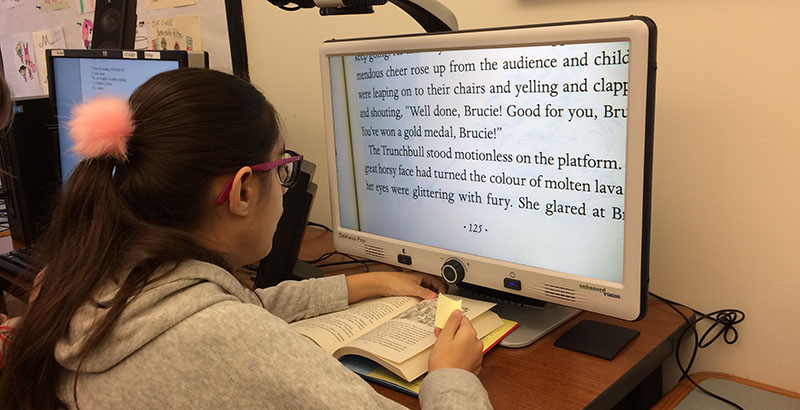

Last month, The 74 published a lengthy follow-up detailing what had and had not changed for Texas children with disabilities. Among the findings: Some 250,000 kids every year have been unable to obtain needed special education services, and the families of students featured in the Chronicle’s initial investigation — including some with profound disabilities — either continued to be denied basic supports or were forced to move to other states to get help.

A Texas Education Agency spokesperson acknowledged the value of special education and said the state is working to improve oversight and support for schools: “TEA agrees that students with disabilities should be provided the appropriate specialized instruction so they can have equitable access to educational attainment. This is why the agency has developed a comprehensive strategic plan and is acting on it to enhance opportunities for students with disabilities in Texas.”

Never before had researchers been able to study the effects of removing students with diagnosed disabilities from special education, because there hadn’t been a control group of children deprived of needed supports. But Ballis and Heath were able to look at similarly situated students who received services before Texas established the cap — decreed illegal by U.S. education officials two years ago — and those whose who were shut out after pressure to cut costs began.

“It’s a really unfortunate event, but it offers a unique setting in which access to special education was curtailed,” said Ballis. “What’s unique about Texas is they also have really good data.”

The researchers looked at the records of some 227,000 Texas students who lost services after the cap was instituted, many of whom had “malleable” diagnoses such as learning disorders, ADHD, speech impediments or behavioral issues. “Malleable” means those conditions were particularly susceptible to being reclassified as something other than a disability eligible for services as pressure to reduce enrollment mounted. In their paper, Ballis and Health refer to these students as “on the margins.”

Affluent students or those in resource-rich districts who lost their special ed services did not experience the same sharp drop in outcomes as their more impoverished peers, the researchers found. The positive impact of supplying resources to this population, the authors noted, is likely as large as that of high-quality early childhood education programs such as the much-studied Perry Preschool.

Other research estimates that up to 90 percent of students with disabilities are capable of performing at grade level academically with the right supports. Yet nationwide, just 20 percent score proficient on state math and reading assessments. In 2017, the four-year graduation rate for special ed students was 67 percent, versus the overall rate of 85 percent.

Ballis and Heath linked student records obtained from the Texas Education Agency to higher education and workforce data. Because there’s no way of knowing which students districts and schools refused to evaluate for disability services during the years the cap was in place, they were able to establish only the effect of losing special ed, not of never receiving it.

One possibility Ballis was careful to note is that the dramatically lowered graduation rate may be related to the fact that students who are in special ed do not take the same high school exit exam as other students. The test may be an impediment for students with disabilities who are no longer receiving special ed services.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)