As Political Winds Shift in Texas, Charter Advocates Plan 2017 Push for Funds to Build New Schools

In the city’s Third Ward, Nikki Knight’s sixth-grade daughter, Dreu, attends class in a temporary, modular building that has so little parking nearby that parents sometimes miss events or teacher meetings because they can’t find a place to leave their cars. Dreu loves dancing and performed in the KIPP Liberation College Prep talent show in December. But because the school has no auditorium or stage, rehearsals were held in the cafeteria, which doubles as a performance space for the school’s 400 students. The students, Knight said, could also use a larger library.

“The waiting list is long because it’s a great campus, [but] the kids, I believe, are a little bit limited in what they’re able to do because they don’t have a full experience because the campus doesn’t allow for that,” said Knight, whose three other children attend both charter and district schools. “In some instances, you give up facility for the benefits that charter schools offer. You give up space for academic exposure, academic opportunity.”

Using modular classrooms or repurposing existing buildings for charter schools is not unusual in Texas because by law, charters don’t have the access to state and local funding for constructing new schools that local independent school districts have.

Charter operators and school choice advocates are hoping to change some of that this legislative session, which begins January 10. But since the Texas Legislature meets for only 140 days every two years, if charter schools are to get the facilities funding they need to meet growing demand, they’ll have to work fast.

The building of YES Prep West in Houston, Texas.

Parents, charter operators and advocates say the nearly nonexistent funding that Texas currently provides for facilities has hamstrung their rapidly growing networks. While some charters, like YES Prep, have found creative ways to expand, others struggle to scrape together resources to accommodate the thousands of students lined up to attend.

“The largest inequity for charter schools is the lack of facilities funding,” David Dunn, executive director of the Texas Charter Schools Association, told the Austin American-Statesman in July. “In 2013–2014, ISDs received $5.5 billion in facilities funding. Charter schools received $0.”

Unlike traditional school districts in the state, charters don’t have local property-tax bases to draw from for building new schools or funding renovations. They don’t get state funding for that purpose, either, unlike regular districts, which received $6.3 billion in state facilities funding in 2015–16, a Texas Education Agency spokeswoman said.

Traditional districts can get local tax revenue to cover debt service on bonds sold to build school facilities, as well as state aid to help poor districts with those debt service payments, she said. But charter schools in Texas get just $250 per pupil from the state for costs associated with opening a new facility, such as purchasing furniture — not for actual construction, and only for two years after the facility opens.

“That has put us into a position with less funding. The only way we can continue to grow is to work specifically on fundraising and philanthropy,” said Keith Weaver, managing director of operations for YES Prep, which has 16 schools in Houston.

The other main source of support is a program offered as part of the Permanent School Fund, in which the state guarantees bonds issued by charter schools and school districts for building costs, and helps ensure reasonable interest rates, thanks to Texas’s sterling AAA credit rating.

“We’re working to get facilities funding for all charter schools, regardless of size, regardless of location,” Dunn told The 74. “We feel like providing facilities is a fundamental necessity for providing a good education.”

Several key initiatives that could advance those efforts during the 2017 legislative session in Austin:

— Property tax relief: Rep. Jim Murphy has filed House Bill 382/House Joint Resolution 34, seeking to exempt charter schools that lease facilities from real property taxes for the duration of the lease.

— Increased borrowing capacity for construction costs: Murphy also filed HB 467, seeking to expand the capacity of the bond guarantee program, which was created in 2014. Fourteen or so charters have maxed out the fund’s $900 million capacity, said Al McKenzie, director of state funding at the Texas Education Agency. “It’s a relatively new program, and there has been a lot of demand for it,” he said. “It’s pent-up demand, as charter schools can now refinance previously issued debt at more favorable interest rates.”

The state Board of Education approved a stopgap measure of sorts in late 2016 to expand the bond fund by $850 million in 2017, but sustaining the fund indefinitely requires legislation.

— Charter school advocates are pursuing other measures that haven’t yet been introduced. One priority, Dunn said, is issuing an updated version of Senate Bill 1900, which seeks to drive tax dollars toward charter schools for facilities needs based on a per-pupil formula.

—Another hoped-for initiative would require the state to consider the financial interests of charter holders when a charter is revoked, a charter school association spokeswoman said.

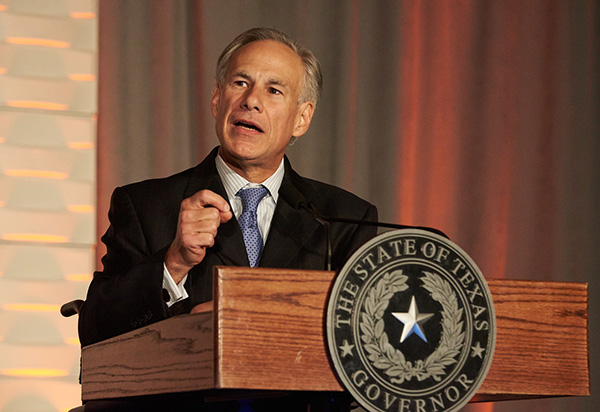

The association hosted Gov. Greg Abbott at its annual conference this fall, the first time a sitting governor had attended the state’s largest gathering of charter school proponents. Before an audience of about 1,600 in Austin, Abbott complimented the “efficiency” and “effectiveness” of the charter schools he had toured and was direct about his support for their growth, though he didn’t go into detail about facilities funding.

“It is time to open more charter schools in Texas and to fund them with the resources they need to succeed,” Abbott said. “It is time to empower all parents in Texas to choose the education pathway that is best for their child.”

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott speaks at the 2016 Texas Charter Schools Conference.

Another key change is the departure of Rep. Jimmie Don Aycock, Republican chairman of the House Public Education Committee, who is retiring. Aycock spent the last two sessions resisting school choice measures that groups like the charter schools association supported.

Aycock’s replacement will be selected later this month. As he was packing up his office in 2016, the House education committee was researching school choice programs at the direction of Speaker Joe Straus, who has said he will “keep an open mind” on school choice initiatives.

Charter schools may also have an ally in newly elected San Antonio Rep. Barbara Gervin-Hawkins, who co-founded a nonprofit to help at-risk youth in 1991 that became one of Texas’s first charter schools. Now known as the George Gervin Academy, it serves pre-K through 12th grade.

“I want to see how traditional public schools and public charter schools can coexist so we can educate all of our children,” Gervin-Hawkins said in a radio interview a week before the November election.

Meanwhile, in the Texas Senate, which has passed several charter facilities funding bills in recent years — only to see them quashed in the House — Education Committee Chairman Larry Taylor believes debates over funding and a separate voucher proposal will resurface this year.

“School choice will be one of the things we’ll be discussing,” he said at a Texas Tribune panel previewing the 2017 session. “Which is the best way for Texas to provide more opportunities for all of our students?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)