Teacher Preparation Needs to Catch Up with School Reform

Kaufman: States and districts are adopting more high-quality curricular materials, but prep programs are not showing new teachers how to use them.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The 2024 National Assessment of Education Progress results show that public school students haven’t made the rebound that everyone had hoped for post-COVID. While math scores rose slightly for fourth graders and did not change for eighth graders, reading scores for both groups of students fell to the lowest levels in decades.

But if classroom instruction isn’t improving, we shouldn’t be surprised that test scores are stagnant or dropping.

How teachers are taught to teach—along with what curriculum materials they use with students and how they use those materials—are the most critical factors for improving student learning. Many state education leaders are doing their part to ensure school districts adopt high-quality curriculum materials and help teachers use them well. The colleges and universities that prepare teachers to enter the profession largely have not.

Back in 2017, the Council of Chief State School Officers formed a network of interested state departments of education – called the High Quality Instructional Materials and Professional Development Network – to put good curriculum into the hands of teachers.

The network is getting its job done: According to RAND’s own research and that of the states themselves, more teachers are using curriculum materials for English language arts and mathematics that are aligned with rigorous state standards. More schools are also providing professional development to teachers that is grounded in their curriculum materials.

Louisiana – a network state that is also a model for state curriculum reform efforts – was the only state to see gains in fourth-grade reading scores on NAEP since 2017. Louisiana and Mississippi, another network member, were two of only four states that have seen gains in fourth-grade mathematics since 2017.

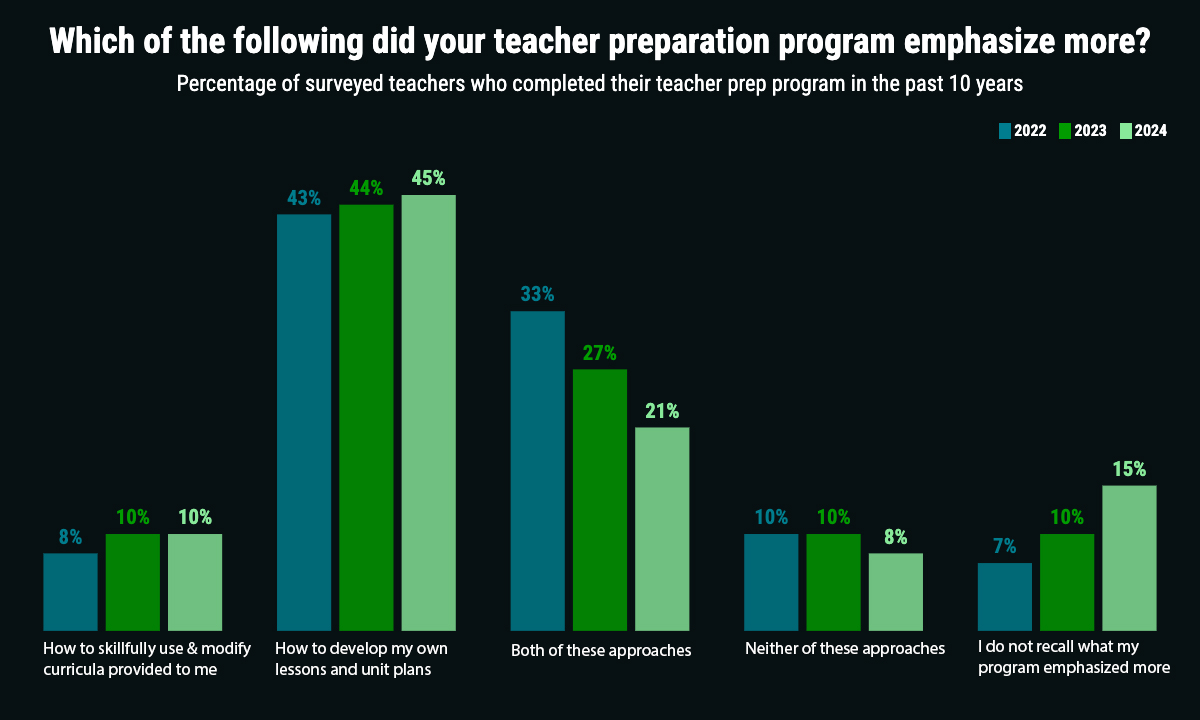

But one area where we consistently have seen little change is in college and university teacher preparation programs. In surveys every year since 2019, RAND has asked teachers across the nation which approach their teacher preparation program emphasized:

(a) “how to develop my own lessons and unit plans,” or

(b) “how to skillfully use and modify curricula provided to me.”

Year over year, only about 10% of U.S. teachers indicate that their program emphasized helping them use curriculum materials. A little less than half say the emphasis was on how to develop their own lessons and unit plans. The balance say their program emphasized both or neither.

These percentages hold regardless of the teacher’s state, whether the teacher is in an elementary or high school; in an urban or rural school; in an English language arts/reading, math or science classroom; or was trained 20 years ago versus in the past five years.

All teacher preparation programs should show teachers-in-training how to skillfully use the curricula they are given. This is a prerequisite to ensuring that most children meet state academic standards. Think about it: If every teacher uses a school-provided curriculum that is aligned with their state standards, the chances of meeting those standards is better than if teachers are reinventing the wheel by developing their own lessons.

Other data beyond our surveys underscore this point: Teacher preparation is slow to incorporate what we know about good classroom instruction.

For example, the 2000 National Reading Panel report and follow-on research confirmed that elementary schoolers need instruction in five key components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Yet, in NCTQ’s 2023 nationwide review of the elementary reading course syllabi of nearly 700 teacher preparation programs, they found that only 25% of those programs adequately addressed those five core components of reading instruction. Another 25% didn’t adequately address any of those components.

The idea that teachers should write their own curriculum is outdated and ill-serving; it’s a holdover from the era before the advent of academic standards in the U.S. and growing knowledge about what makes a good curriculum material. These days, according to a recent RAND American Instructional Resources Survey, less than 2% of school principals encourage teachers to develop their own curriculum. Instead, most principals expect teachers to use their required curriculum materials.

At their best, professional curricula are developed by experts in subject matter and pedagogy, are written to build students’ knowledge over time, and have been endorsed by third party organizations such as EdReports that deem the material aligned with state academic standards.

Adopting a prepared curriculum needn’t turn teachers into robots; it takes considerable skill and subject-matter knowledge to use any materials thoughtfully and productively. Teacher prep programs should give teachers ample, hands-on training on how to use their grade-level curriculum materials and the expertise to make just-in-time adjustments that help students catch up when they are struggling to master those materials.

States and school districts know that curriculum matters. Many have revamped their policies accordingly. It’s time for teacher preparation programs to do the same.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)