‘Tangible Equity’: Excelling at — and Then Dismantling — an Unfair System

Author Colin Seale argues it’s not enough to teach students how to overcome the odds, but to challenge how those odds are stacked against them

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This essay is excerpted from the new book “Tangible Equity A Guide for Leveraging Student Identity, Culture, and Power to Unlock Excellence In and Beyond the Classroom” by Colin Seale

In the introduction, I defined equity as reducing the predictive power of demographics and zip codes to determine the success of young people inside and outside of the classroom to zero. This utopian idea sounds too pie-in-the-sky for a book called Tangible Equity. But there is a reason I set forward such an extreme, unreachable goal for equity: the process matters more than the outcome.

The Tangible Equity process is part of my personal journey. My story, as a Black child receiving free and reduced lunch from a family of immigrants with an incarcerated father, is one of bucking the highly predictive power of demographics on student success. On demographics alone, I am the type of student our educational system typically does not serve that well. Making matters more complicated, I was not just a bad first grader — I was gifted at being bad. I went above and beyond in my mischief. Looking back at my behavior as an adult, I realize that the greatest crimes I committed were not quite the acts of terror they were painted as at the time.

Apparently, I talked. A lot. To everyone. At any time. It did not matter how many days in a row I would lose recess as a punishment, I was going to talk! It is worth noting that taking recess away from a high-energy child is probably going to punish that teacher post-lunch much more than it punishes the child. I was shocked to learn as an adult that at some point, my mother told my third-grade teacher she was no longer allowed to call her to complain about my unappreciated gift of gab. She couldn’t figure out how to stop me from talking either! So deal with it! With the hundreds of keynotes, YouTube videos, podcasts, and panels I speak on each year, maybe talking in class was not really willfully defiant after all.

I was also a repeat offender of the serious felony of excessive question-asking. Because how dare I ask “why” and protest that “it makes no sense” to write the word “paint” ten times when I already knew how to spell it before class even started? My most terrible act? Fighting my teacher. Not fist-fighting or physically attacking my teacher. I’m from a Caribbean family and I learned in pre-school that my family’s old-school method of parenting and my highly-sensitive rear end were not compatible, so I was not going to go there. By fighting, I mean having the audacity to question the way a teacher was doing something, or even worse, suggesting that she ought to do that thing my way instead.

As “bad” as these so-called behavior challenges were, they all stemmed from the same root: a lack of being challenged. As you read that last sentence, can you think of a child who shares my story? Behavior challenges arising due to a lack of academic challenges? I want you to personalize this as much as possible because a major event happened in my academic career that can certainly happen for the child you are thinking of right now. That major event was my accidental identification into the New York City Department of Education’s gifted and talented program. This was the most transformational experience in my educational career. But you know what the biggest transformation was? The fact that I did not change.

I was still the same Colin. But I was no longer “bad,” I was gifted. Talking was far less offensive in a class where student-centered work, student-centered inquiry, and basically student-centered everything was simply the way it was. We were the classroom that frequently got that knock from the law-and-order teacher next door about needing to tone it down because her students were almost always at Level 0 (complete silence) while learning. And for some reason, these students then and students I see in classrooms across the country today are often asked to be at Level 0 for all sorts of things that have nothing to do with learning. But that is an issue I will get to later in the book. Another transformation? Asking questions was no longer disrespectful. Asking questions was now required for what it meant to be inquisitive and curious. When Mr Eisenberg wanted me to do the required math fair project on fractions with some annoying, unoriginal recipe assignment about multiplying fractional quantities to feed the school what I was certain would be subpar cupcakes, I refused! I told him it was boring, dumb, and I did not want to do it. This would have been a no-recess-for-life moment in another classroom. But for Mr Eisenberg, he was as cool as the other side of the pillow:

Him: “Do you have a better idea?”

Me: “Of course I do! I play piano and I want to do a project called Fractional Music where we look at all the ways fractions show up in music with quarter notes, half notes, triplets, dotted quarter notes, etc.”

Him: “Class, Colin had a different idea for the math project. Colin, explain what you were saying.”

Me: “I am brilliant. Just do what I say because I am brilliant.” (paraphrased)

Class (in unison): “Colin is brilliant! Let’s just do what he says because he is brilliant.”

(100% accurate, word for word)

What could have been a moment of willful defiance in any other classroom became a moment where my advocacy and leadership was encouraged and celebrated. This memory helps me see that I omitted a huge piece of the puzzle in my zealous advocacy for a critical thinking revolution in education. There is a massive prerequisite for critical thinking to flourish in today’s education system that is almost entirely an adult issue: ensuring children have the safety to be brilliant. In many of our hyper-compliant, rules-over-everything classroom environments, I question whether these spaces are psychologically safe for students to wonder, ask, speak up, collaborate, offer alternatives, think creatively and do all the things we associate with 21st century readiness.

Culturally, my Caribbean upbringing, like the upbringing of many immigrant households and other super-strict families, was one where “because I said so” was a good-enough justification for parents to do just about anything. But when we think about the safety to be brilliant, do we ever ask ourselves why parent phrases like “don’t get smart with me” exist? It is hard for me to think that the grave consequences Black folks could face historically for “getting smart” with the wrong white person does not play a role in this type of rhetoric. I have undocumented family members. So, I am also very familiar with the guidance, said or unsaid, that children of undocumented parents receive about not shining their lights too brightly in school to avoid raising unnecessary attention.

Tangible Equity recognizes that we cannot rest on proclamations and resolutions about how much we care about and value student diversity. It makes no sense to have this beautifully diverse set of students and ask them to spend most of their time conforming to what we deem “normal.” There is no value to our students’ diversity if we do not find ways to allow them to be themselves as a regularly-scheduled aspect of their learning process.

This resonates with me because I have experienced the downside to what happens when we do not create the psychological and actual safety students need to exercise their brilliance. I lived the student experience of never having a learning space speak to the magic of my identity, and I know that I am not alone. My elementary school, self-contained gifted class bussed in some of the most brilliant children from South Brooklyn. But as amazing and transformational as this experience was, I spent years scratching my head about why three of these students did not graduate from high school. Not graduate school, not college, but high school. Mind you, my classmates and I all started high school at least one or two grade levels ahead because of high school credits we earned in middle school. Still, three did not graduate, and I was so close to being the fourth one with the 80 absences I had in ninth grade.

Why does this happen? Why do we have so many children who are rock stars in their earlier grades, but go through this process where the longer they are in school, the less they are into school? I have more questions than answers, and there are plenty of amazing scholars who research this question in more detail. I just know that the painful sight of leaving genius on the table was unbearable for me.

This sight stuck with me when I became a teacher. I was the outcomes-over-everything educator to the extreme. I was not pro-high stakes standardized exams. But I was, and still am, pro-reality. Leveraging Tangible Equity’s power must involve interrupting intergenerational poverty. As an educator, therefore, I had to ask myself a simple yes or no question: is education an important part of disrupting intergenerational poverty? Yes or No? Mind you, I’m not asking whether education is the be-all, end-all. But I doubt any reader of this book would doubt whether education was at least an important part of what it takes to interrupt intergenerational poverty.

If we believe this, we must also be able to look into our classrooms and see our students as future doctors, lawyers, engineers, nurses, and even future teachers. This means they have to pass tests. A common objection usually occurs around this time where someone chimes in saying “college isn’t for everyone.” When we say this, we miss the reality that the power of a thoughtfully financed college degree is undeniably transformational, particularly for women and people of color. Given the vast improvements in earnings with a four-year college degree vs anything less than this, it literally still pays to go to college. But in recognition of the growing opportunities for well-paid, high advancement potential fields that do not require a four-year college degree, we should be clear that tests are still necessary. Plumbers still have to pass tests. So do police officers. We cannot talk about Tangible Equity without talking about the outcomes needed to fulfill the promise of Tangible Equity.

Equity of outcomes sounds utopian. I am often asked, “don’t you mean to say equity of opportunity?” The answer is no. I mean to talk about the equity of outcomes. Recall that I am defining equity as reducing the predictive power of demographics on outcomes. This means that changed outcomes are the only way to show that the predictive power of demographics has been reduced. Fortunately, the equity of outcomes is tied to equity in opportunity in significant ways. I would not have received a transformational educational experience had I not been accidentally identified as gifted and bussed to a gifted and talented program outside of my neighborhood. For brilliant students with no such program within bussing distance and without transformational learning options in their neighborhood schools, they do not have this opportunity. But even if they did, opportunity itself would not be enough.

Let’s use basketball as an example. Pedro Noguera often uses an example of the National Basketball Association that I want to borrow to explain why opportunity is not enough. In 2020, although Black people represented 13.4% of the population, Black players in the NBA represent 75% of all NBA players. This statistic is often used by doubters, who say “See! Racism and poverty are just excuses. Black athletes’ dominance and prominence in basketball proves that if they cared about school as much as they cared about shooting hoops, these inequities would not exist.” But Noguera offers brilliant insights to counter this flawed reasoning that uses basketball to teach us what an equity of outcomes could look like in education.

In basketball, the rules are standardized and common to all players. The rim is always ten feet off the ground. Basketballs must be inflated between 7.5 and 8.5 pounds. The free throw line has to be set 15 feet away from the face of the backboard. The point system is standardized and common to all players. A basket in the hoop counts for two points during play. Free throws count as one point. Anyone gets three points for shooting the ball from 23’9” away from the middle of the basket. These rules are the same no matter what state you live in, what basketball court you are playing in, how much money your parents earn, the zip code you live in, your race, your ethnicity, your native language, or your parents’ educational level. Basketball, therefore, is a level playing field. The rules of playing the game and the rules for winning the game are always the same. I can therefore conclude that athletically gifted basketball players who do not get injured and put forth the time, effort, and hard work to reach greatness have as much of a shot at NBA success as anyone else with similar situated gifted, healthy, athletes who exert the same time, effort, and hard work.

We are nowhere close to this in education. The only universal standard in the United States’ education system is that nothing is universally standard. Outcomes must be tied to opportunity because equitable opportunity is not enough for a brilliant child who is the fourth generation of her family to grow up in an economically disadvantaged trailer park community. She can have a 4.0 grade point average and even be the valedictorian of her class. And even with this impeccable resume, she could still not be accepted to highly selective universities. As outrageous as this might sound, it is even possible that she could graduate at the top of her high school class and not meet the course requirements to enroll in her state’s flagship public university. This is not to say merit does not matter, because it does. But merit, alone, is not enough.

When we consider the extraordinary educational effort required to transcend intergenerational poverty, the time, effort, and hard work are not measured by any sort of standardized or common set of rules. Do you remember the wild Varsity Blues scandal that revealed the lengths wealthy families went through to buy their children access to universities through bogus sports accolades, extra-curricular activities, and faked test scores?7 This illegal scandal pales in comparison with the very legal system that gives the super-privileged access to (and the ability to afford) prestigious unpaid internships, and the pay-to-play social capital system from prestigious pre-kindergarten programs to Ivy League feeder high schools. These are not the same rules. This is not even the same game.

This reality is not news to those growing up in the struggle. Part of why I push so hard for equitable outcomes goes beyond knowing our students need to pass tests to be future doctors, lawyers, engineers, nurses, and even future teachers. Because this is so much more complicated than simply passing tests. As an immigrant, my mother was raised under the mantra that she had to work twice as hard to get half as far. She raised me to understand that as a Black boy growing up in Brooklyn, I was also required to work twice as hard to get half as far. As a father to two young children, I feel completely ashamed that at some point, I need to explain the same thing to my children. I am truly ashamed of myself.

I have dedicated so much of my life to ensuring that stories like mine are no longer the exception to the rule. Yet, I have spent so much of my energy challenging myself to successfully navigate this unfair system instead of challenging the unfair system itself. The rules for playing the game and winning the game are not standardized and common. The rules are highly dependent on what state you live in, what kind of school you go to, how much money your parents earn, the zip code you live in, your race, your ethnicity, your native language, or your parents’ educational level.

In education, we are still very far from being able to conclude that academically gifted students growing up in the struggle who put forth the time, effort, and hard work to reach greatness have as much of a shot at successful educational options as anyone else with similar gifts who exert the same time, effort, and hard work. Yet, I have spent so much of my energy helping children master all the tricks and shenanigans of playing an unfair game. What would happen if instead, I focused more on what it would take for them to master the skills needed to slay the game altogether.

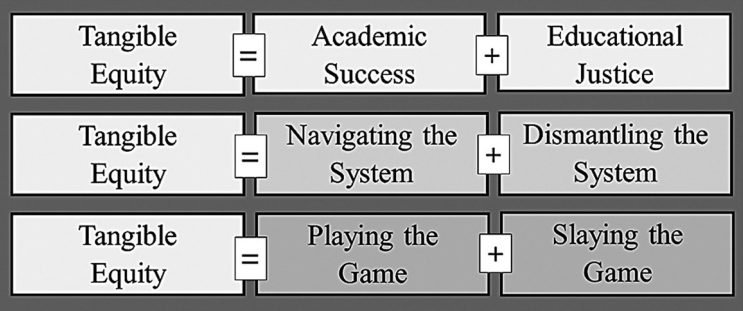

Tangible Equity is not an either/or challenge? Academic success must be present for Tangible Equity to exist. But as long as a child’s race, income, and zip code translates to requiring extraordinary levels of academic success to reach ordinary outcomes, academic success is not enough. We need academic success and educational justice. Educational justice would mean getting our system to be similar to the standardized and common rules of basketball. The math teacher in me recognized the need for a formula to describe what I am trying to say here in a way that breaks it down more clearly in Figure 1.1.

Think about how often we celebrate stories of children who grow up in the struggle, overcome all sorts of unfair obstacles, and “make it.” The Tangible Equity Equation helps us rethink what it means to truly “make it.”

I recall my experience as a Computer Science major selected for the amazing INROADS program. This non-profit organization’s vision of diversifying Corporate America is 50 years strong, and I was proud to go to New York City and meet lots of other Black and Brown college students aspiring for internships that would put us on the path for lucrative, successful careers in Fortune 500 companies. I remember attending a workshop on how to dress appropriately.

All of us college students had our most professional clothing on, but I only heard what they told us young men because young women received a different workshop. I learned that facial hair was a no-go. I learned that bright-colored shirts underneath my suit were loud and improper. I learned that cornrows were unprofessional. Wearing my hair in twists or locks? Completely unacceptable. I learned how to sit. I learned how to look someone in the eyes and give a firm handshake. How to speak, sit, question, and answer professionally. I could only imagine the kind of lessons the young women learned about how not to dress and how not to style their hair. By the end of the day, I learned the hidden curriculum of how to succeed in Corporate America.

The most important lesson of this hidden curriculum was that important pieces of me needed to stay hidden. The two Black men presenting this workshop were passionate, funny, cool, and caring. They wanted nothing more than to open doors for us, doors that would not be opened if we could not master all the necessary ways-of-being that make these lucrative careers accessible to Black and Brown college students. We had to be “professional.” As uneasy as I felt about this, I carried this same mindset into my classroom. I spoke frequently to my students about code-switching so they understood that when they were in “professional” settings they needed to act differently. Speak “properly.” Act “appropriately.” Because again, if we want to realize the potentially transformational impact of education for students most impacted by the ills of racial discrimination and poverty, access to successful career paths matters.

Something always bothered me about my INROADS experience. If diversity is such an asset to Corporate America, why would they require folks from diverse backgrounds to conform in such an extreme fashion? How could they realize the benefits of my diverse perspective and unique understandings if I am asked to hide so much of myself to even gain access to the entry level? It is even more bothersome when I realize that I attended this INROADS workshop in the year 2000. In the 20-year period after that workshop, Fortune 500 companies have had only 16 Black CEOs, 36 Latinx CEOs, ten East Asian CEOs, and 22 South Asian CEOs. With only 72 white women holding at the helm during this same time period, leading in Corporate America is still clearly a white man’s game.

Again, there is nothing inherently wrong about teaching our young people the hidden curriculum to successfully navigate an unjust system. But at what point do we teach them how to use their access to the system to question it, reimagine it, and dismantle it altogether? From an educational perspective, it is hard to think about classrooms that equip young people with the tools to lead, innovate, and break what needs to be broken when students still get in trouble for asking too many questions. I cannot envision a dismantling of unjust systems when it is still far too common for classroom teachers to punish student leadership and advocacy as “willful defiance.”

I understand and value my mother’s journey and why working twice as hard to get half as far mattered so much to her life that she had to pass that lesson onto me. I understand and value the journey of the gracious Black men who took a Saturday break from their challenging positions in Corporate America to school us to the tricks we needed to master to access these lucrative career fields. But the work of reducing the impact of demographics on the predictability of outcomes requires that we put equal effort into helping young people know what it takes to play the game as we do equipping them with the transformational tools needed to slay these unjust games altogether.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)