Supreme Court Rules 9-0 in Favor of Deaf Man in Special Education Case

Students can seek monetary damages even if they accept a settlement under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the court said.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A deaf man can sue his former school district in Michigan for monetary damages because he was denied appropriate services and left unable to communicate in school, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously Tuesday.

The justices reversed a decision by the Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit that prohibited Miguel Luna Perez from seeking financial relief under the Americans with Disabilities Act because his family accepted a settlement under special education law.

“We clarify that nothing in that provision bars his way,” Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the opinion, referring to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. He added that the court took the case because it has consequences for “a great many children with disabilities and their parents.”

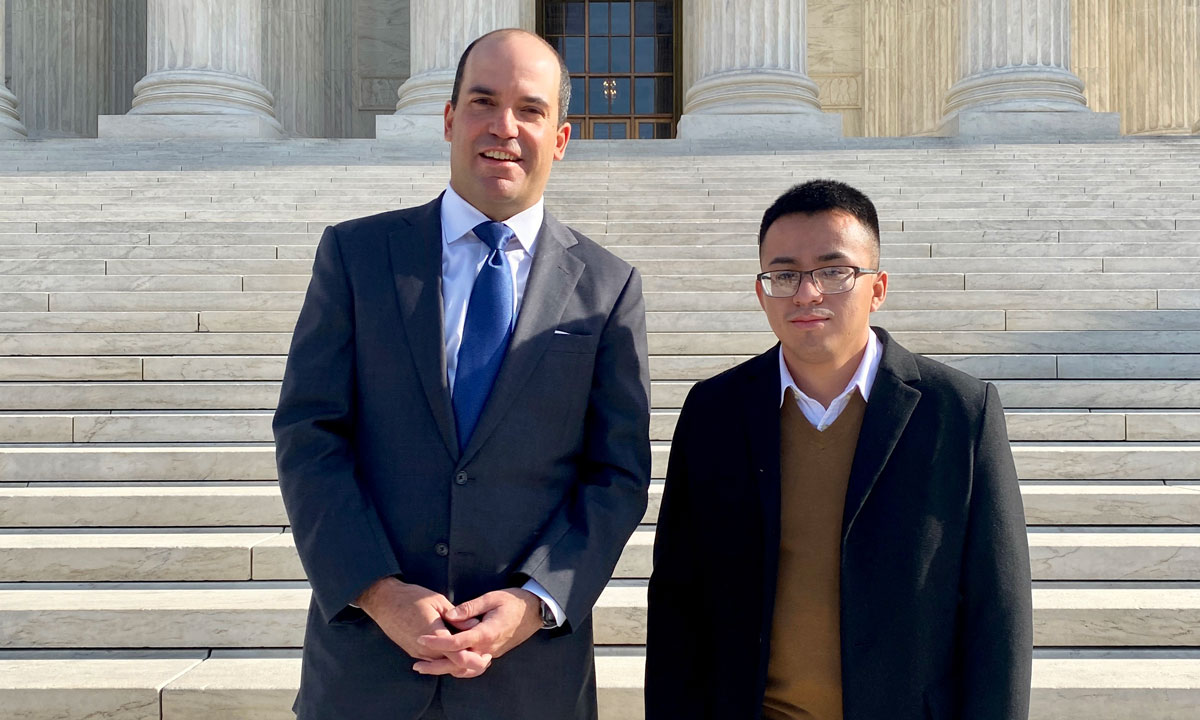

In a statement, Roman Martinez, Luna Perez’s attorney, said the family now plans to pursue a lawsuit against the Detroit-area Sturgis Public Schools under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The “court’s ruling vindicates the rights of students with disabilities to obtain full relief when they suffer discrimination,” he said.

The case focused on whether Congress intended for families to relinquish their rights to sue for monetary damages when they agree to a settlement under IDEA to get their children services as quickly as possible. But advocates for school districts, such as AASA, the School Superintendents Association, argued that districts could be facing multiple lawsuits from the same family.

“This is a significant ruling, and an unsurprising decision based on the oral argument,” said Sasha Pudelski, advocacy director for AASA. “We have deep concerns with injecting a legal battle over money into the IDEA process and how this ruling may undermine parents’ willingness to collaborate with districts in crafting an appropriate special education program for a child.”

Luna Perez, whose family emigrated from Mexico, entered the Sturgis schools in 2004, when he was 9. He didn’t know American Sign Language or English. The district assigned him an aide who couldn’t sign, invented hand signals to communicate with him and often left him alone for hours.

He received good grades, but before graduation in 2016, the district told his parents that he would not be eligible for a high school diploma — only a certificate of completion. The family sued under IDEA, which resulted in a placement in the Michigan School for the Deaf. But the family also argued that their son should be compensated for being left without the skills to get a job. IDEA includes a number of procedural steps before a case can go to court and doesn’t provide financial relief.

The only remedy available under IDEA is compensatory education services. But Rebecca Spar, a special education attorney with the New Jersey-based Education Law Center, said that’s less important to an adult who needs to support himself.

“It was the kind of case where appropriate education going forward could not remediate the harm to the student,” she said.

Advocates for English learners said there are lessons in the case for how districts serve immigrant families whose children have disabilities. Schools need to ensure immigrant families understand their rights and provide interpretation and translation services, said Cady Landa, a researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who has studied the obstacles facing such families.

In the Sturgis schools, things have changed since Luna Perez was a student, said Superintendent Art Ebert, who has been with the district since 2018. The district has an interpreter and is expanding its special education department. Depending on their needs, some students with disabilities attend programs offered by county-level intermediate districts if local schools can’t provide the services.

“I do believe that every experience provides us with an opportunity to learn and grow,” Ebert said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)