Support for Testing and Accountability Is Waning. Is Politics to Blame?

Hartney: It reflects the unwillingness of the political class to make holding schools accountable for learning the cornerstone of American education.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

We’ve long known that politicians influence how ordinary Americans think about education issues. Voters “follow the leader” — embracing or rejecting policies championed – or opposed – by elites in their political tribe.

Of course this phenomenon isn’t unique to education. But its problematic effects have played an outsized role in the K-12 arena in recent years.

First, there were the COVID-era school closures. The effort to reopen schools was initially untainted by partisanship. But when President Donald Trump championed in-person learning in the summer of 2020, reopening became coded in red and blue. Democratic politicians and teachers union leaders swiftly rebuked Trump on the issue. Ordinary voters responded in turn. Reopening then became a partisan quagmire that put kids last.

But as has been well documented, the decline in student achievement wasn’t just a pandemic phenomenon. The decline began much earlier, exacerbated during the retreat from consequential accountability, and steepened even more post pandemic.

As student outcomes remain moribund today, leaders in both parties are doing far too little to reverse these trends. This time around the obstacle isn’t COVID reopening battles or culture wars. It’s mainly about the unwillingness of the political class to signal, in a bipartisan manner, that holding schools accountable for student learning must be the cornerstone of American education.

As Harvard Education professor Martin West recently put it while digesting the results of another disappointing NAEP assessment, “There is good evidence… that really does suggest a lot of [the academic] progress in the 1990s and 2000s was driven by test-based accountability.”

Unfortunately, according to newly released survey data, accountability advocates have lost the public, and Democratic voters in particular.

As part of the 2024 Cooperative Election Study (CES) survey, I asked a national sample of voters two questions about their support for the two key pillars of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) reform agenda: testing and accountability. Crucially, these questions were asked using the same language that pollsters at PDK/Gallup used back in 2001. Specifically, voters in both surveys were asked: Would you favor or oppose each of the following measures that have been proposed as part of a national education program in the US:

- Increased use of standardized tests for measuring student achievement

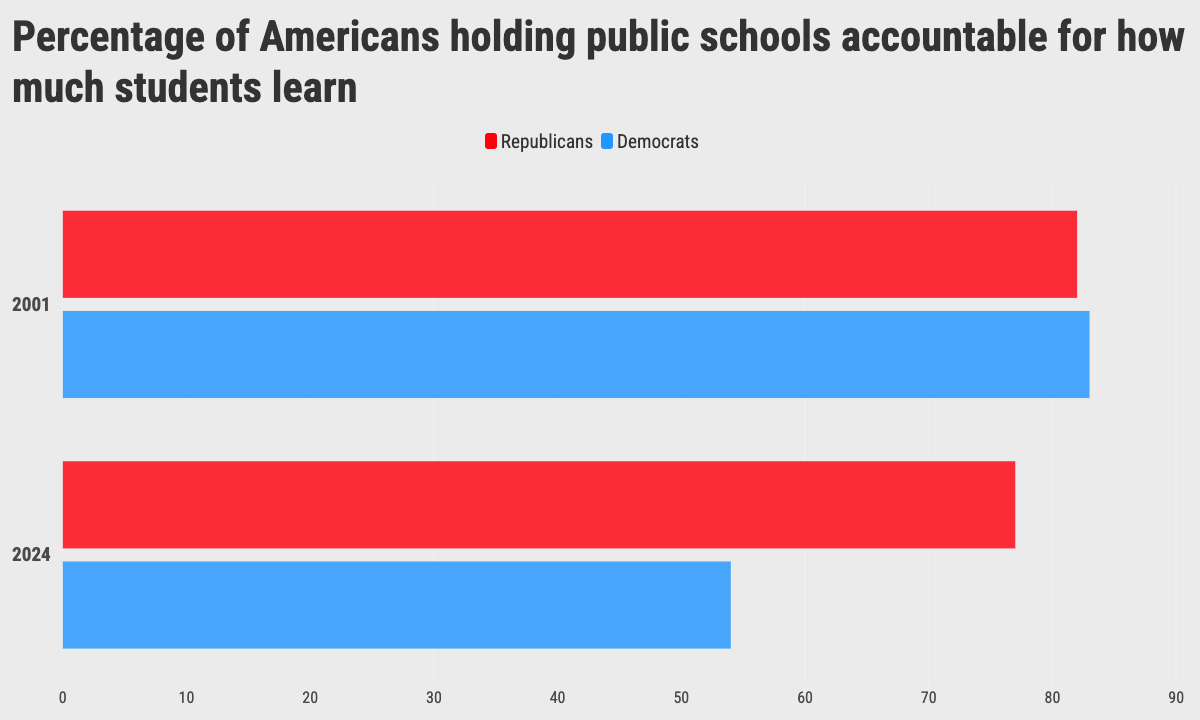

- Holding the public schools accountable for how much students learn

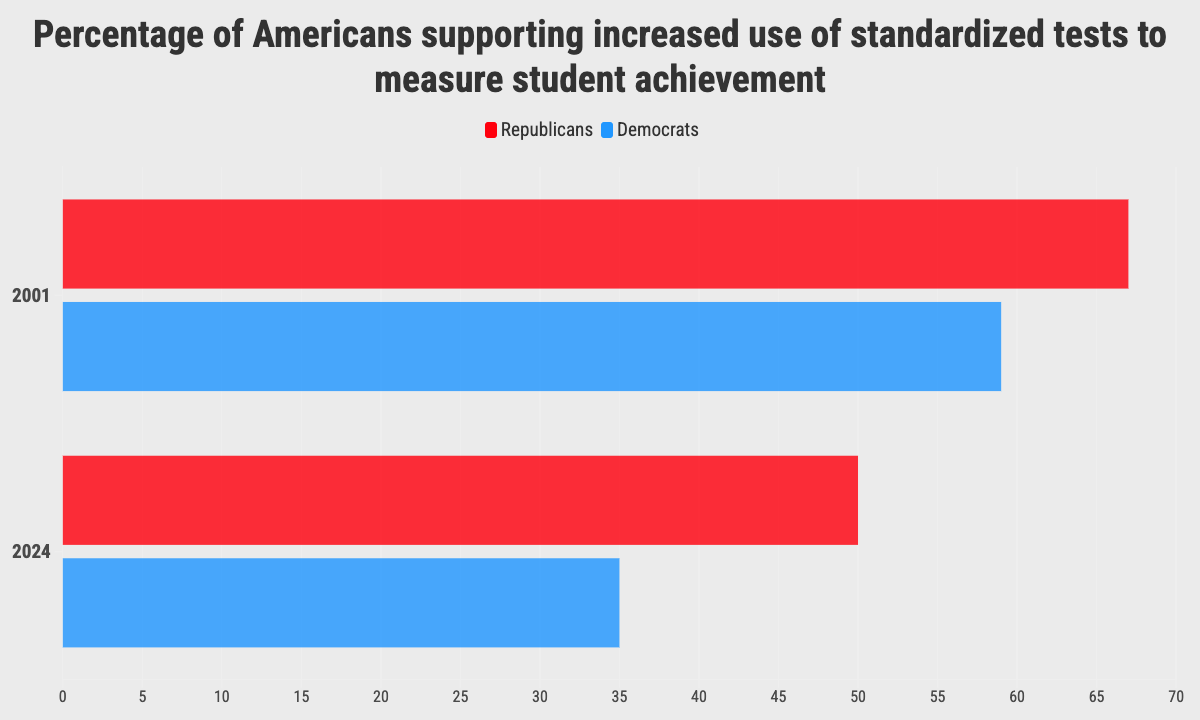

The chart below displays the percentage of Americans, separately by political party, who said that they favor increased use of testing to measure student achievement.

While it’s true that support for standardized testing has declined among all Americans – no doubt due in part to over-testing during the height of NCLB – the drop has been far more concentrated among Democrats. Whereas six in 10 Democrats favored more testing to measure student achievement back in 2001, today just one in three do (Figure 1).

But the Democratic backlash to the bipartisan reform agenda goes beyond an aversion to more testing. Democrats have also lost faith in accountability. Back when the Bush administration was lobbying to enact NCLB, Democratic voters favored holding schools accountable for student achievement slightly more than did Republicans. In the intervening decades, however, Democratic support for accountability has nosedived.

Why have Democrats soured so much on testing and accountability?

The answer surely has something to do with “follow the leader” politics. Democrats’ attitudes followed a major change in the way prominent Democrats spoke about school reform. Leaders, including President Joe Biden, spurned President Barack Obama’s reform agenda and instead embraced the teachers unions’ anti-testing and accountability posture.

Since then, ordinary Democratic voters have taken notice.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, teachers unions pushed for a permanent end to high-stakes testing in Massachusetts. In 2024 they succeeded: The state’s overwhelmingly Democratic electorate voted against keeping passing MCAS as a graduation requirement.

While it’s unlikely that voters soured on reform solely because their party and union leadership did first, there is some evidence consistent with this follow-the-leader dynamic.

Since Barack Obama left office, rank-and-file Democrats have become far more supportive of teachers unions. For example, in 2014, Harvard’s EdNext poll found that one in four Democrats believed teachers unions had a negative effect on schools. A decade later, my CES survey, asking an identical question, found that just one in 20 Democrats view the unions negatively. Instead, six in 10 said teachers unions have a positive effect on schools.

Notably, it is the larger base of pro-union Democrats who are more likely to oppose test-based accountability than their fellow Democrats who are union skeptics. The bottom line: Testing and accountability became less popular among Democratic voters after the party’s elected officials and their powerful labor partners firmly united publicly against these positions.

Although we can’t disentangle cause and effect with precision here, this timing is consistent with political science research that shows voters often take cues from political leaders, rather than independently forming opinions first and influencing politicians.

As Democrats gear up to try and win back the White House in 2028, the party’s choice in a standard bearer will have important implications for the future tone and direction of education politics.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)