Study Shows New Orleans Students More Likely to Stay in Same School After City’s Education Reforms

The rate at which students move between elementary and middle schools in New Orleans has decreased in the wake of post-Hurricane Katrina reforms that brought more charter schools, higher test scores, and considerable controversy to the city. That’s according to a study released today by Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance, only days after the state returned control of schools to city residents.

After the storm devastated New Orleans classrooms, the vast majority of the buildings were converted into charter schools. At the same time, education spending increased and test scores were used to hold schools strictly accountable for performance. Critics of the dramatic shift argued that the changes increased churn of students significantly, forcing students to transition between schools in a persistent state of flux.

The latest data doesn't find much support for those criticisms, and if anything shows that switching schools decreased after the reforms. The authors note, however, that more advantaged students tended to see the largest decreases in mobility, raising new concerns about equity.

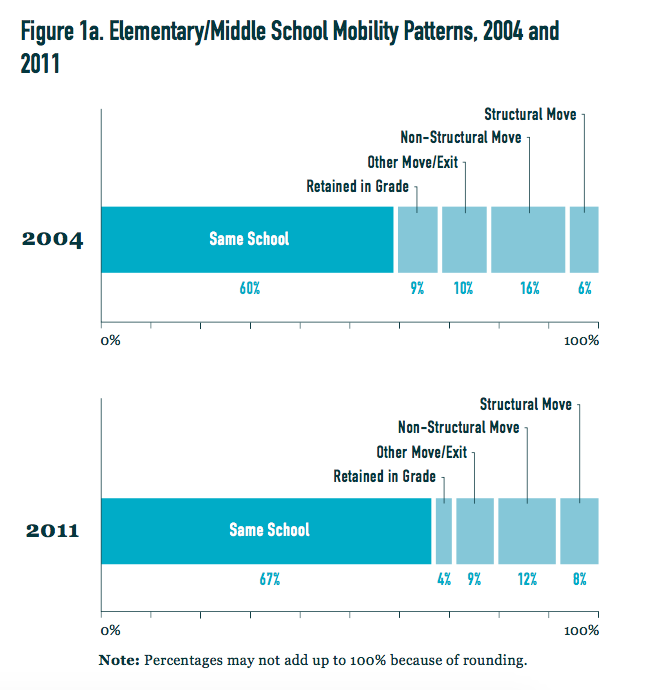

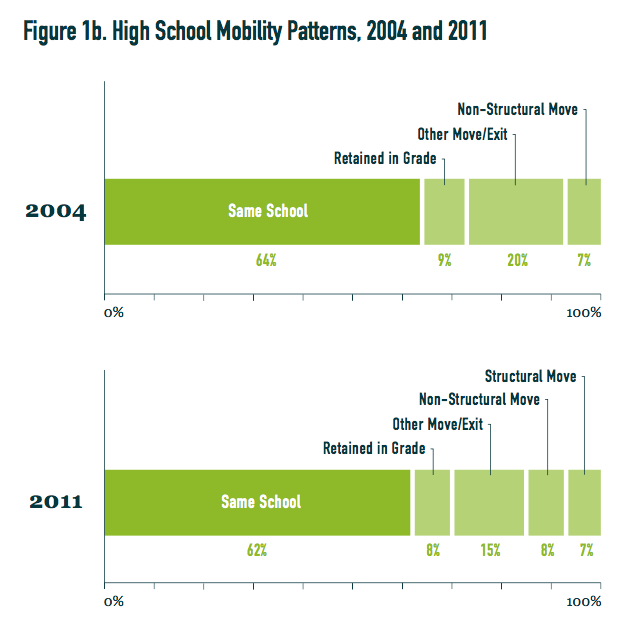

Today’s study examined student mobility in New Orleans the years preceding (2001–2004) and following (2008–2011) Hurricane Katrina. At elementary and middle schools in 2004, 60 percent of students remained at the same school as the prior school year; in 2011 the number had jumped to 67 percent. In high school, though, mobility increased two percentage points, which the authors attribute to the fact that some charters did not cover all high school grades. Across all school levels, there were small drops in the number of students exiting the system altogether.

These findings are important because, as the authors point out, “research consistently shows that mobility leads to worse student outcomes.”

Photo: Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance

Photo: Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance

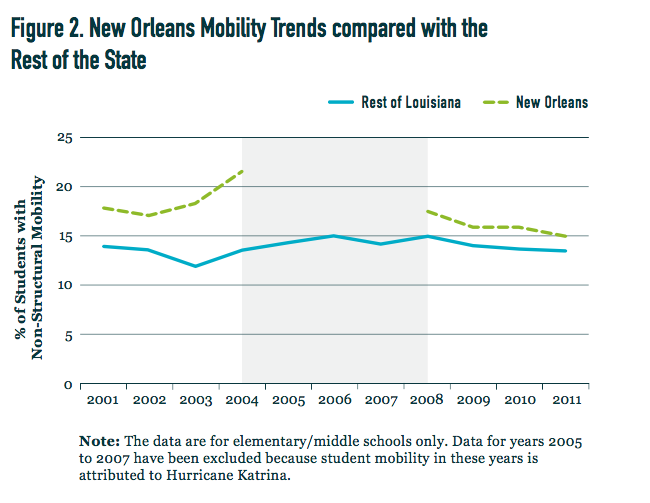

Because it’s generally when families have the most discretion about whether to switch schools, the study emphasizes “non-structural mobility” — referring to when students move schools within the system for reasons other than finishing the last grade offered at the school. The data shows that this type of mobility has decreased in New Orleans compared to the rest of Louisiana.

Photo: Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance

The research can’t say what caused the decrease in mobility. “It is a bit harder to prove causality in this case since we don't have data on housing mobility, which would also affect student mobility (though we think that housing mobility is actually driving mobility upwards),” wrote study co-author and Education Research Alliance director Doug Harris, in an email to The 74. The researchers posit that mobility decreases may have been because of improvement in school quality or match with students.

There have been nagging questions, however, about whether the underlying data on New Orleans’ schools is accurate; some reports suggest that graduation rates may have been inflated due to how students leaving the system were coded in state data.

Harris, via e-mail, said: “We are aware of the concerns that critics have raised about the data in general and we take those seriously, although we are not aware of concerns that would affect our mobility calculations. The fact that only one school can receive money for a given student (based on the enrollment data), and that schools have an incentive to report students as enrolled, gives us confidence in these cross-year mobility figures.”

Watch The 74 documentary: Katrina + 10 — The rebirth of New Orleans’ Schools

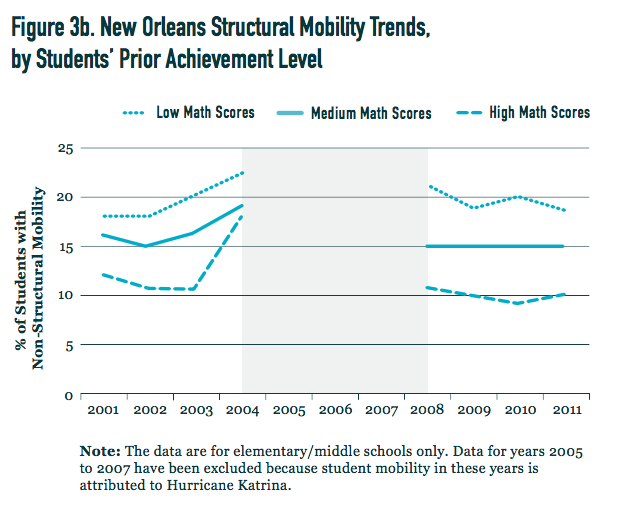

Today’s findings do raise fresh concerns about equity. Although school switching rates dropped for all students, in general they declined at faster rates for more advantaged students. “Mobility has decreased for students with medium and high test scores, but remained fairly steady for students with low scores,” the study says.

Photo: Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance

Moreover, while students with middling and high test scores tended to transfer from lower to higher achieving schools, the same wasn’t true for low-scoring students, who generally moved between schools of similar performance. This means, the researchers write, that it’s possible certain “schools could be cream-skimming higher achieving students and limiting the enrollment of lower performing student.” Another study from the Education Research Alliance found that one in three principals in the city admitted to attempting to avoid struggling students in order to boost test results. (This research took place in the first year of implementing a centralized enrollment process, and some supporters of city’s reforms say the new system has ultimately cut down on the practice, though no public data exists to confirm this as of yet)

Previous research from the Research Alliance showed that the package of New Orleans reforms produced large test score gains for all students — though the improvements were greatest for white and higher-income students who make up a small fraction of the city’s public school population. Surveys show that white New Orleanians on average have a more positive perception of city schools than black residents.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)