Study: Math Scores Matter More for Adult Earnings Than Reading, Health Factors

An Urban Institute study underscores the need for better math instruction starting in the early grades.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When it comes to factors that affect a student’s well-being in adulthood, better math skills might not be the first thing that comes to mind. But as it turns out, increasing math scores helps deliver stronger long-term returns for students — especially related to earnings — than improvements in reading scores and factors involving health.

That’s one of the top-line findings from a 2024 report from the Urban Institute, which sought to understand whether devoting resources to children’s health and social development yields greater benefits than devoting resources to their cognitive development; the study also looks at what aspects of a child’s cognitive development play relatively larger roles in their adult outcomes.

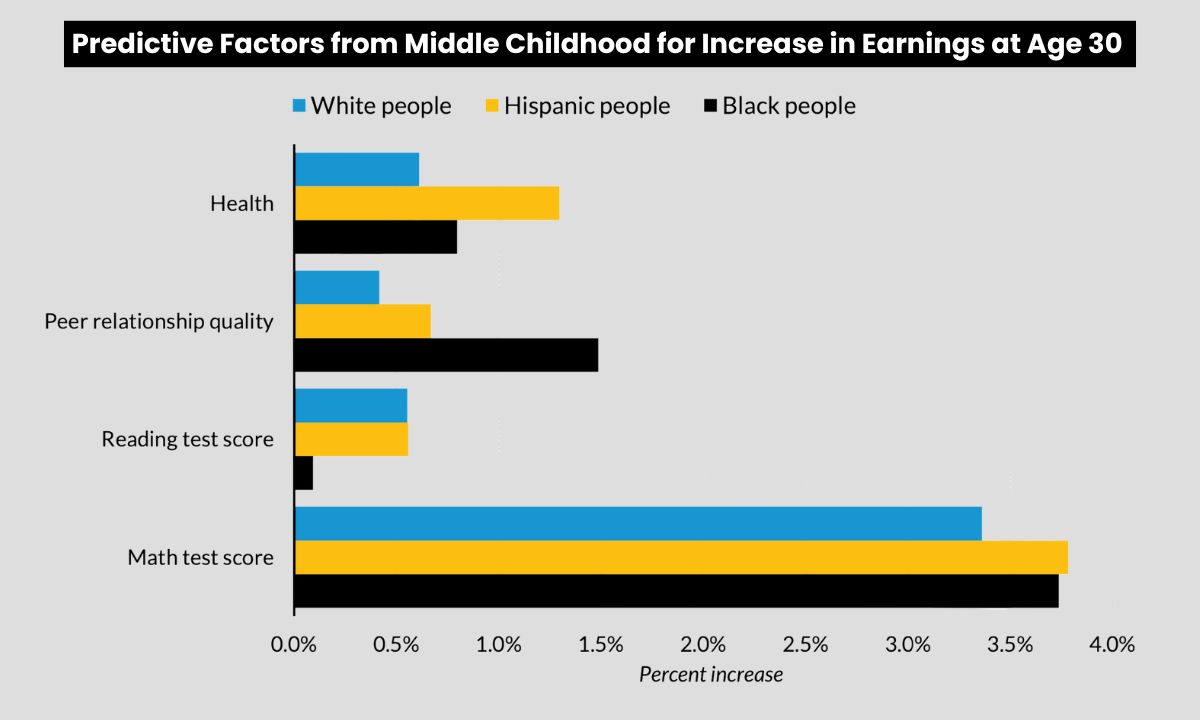

Researchers found that math scores have a significant predictive impact on earnings into adulthood. That finding holds true for children of all races and ethnicities – including for Hispanic children who consistently experience the largest gains – and for girls, who tend to see a higher earnings boost than boys.

“Math scores seem to matter a good bit,” says Gregory Acs, vice president for income and benefits at the Urban Institute and one of the lead authors of the policy paper. “Everything matters a little, but cognitive skills seem to matter a lot.”

The findings, which replicate a longstanding correlation between math and adult success, come as school districts across the country consider ways to provide more effective math instruction, especially in the early elementary years, and build a stronger connection in the K-12 setting to local workforce needs.

Specifically, the analysis shows that improving math scores by 0.5 standard deviation for children up to age 12 is associated with larger increases on earnings by age 30 than other equivalent improvements.

The impact also increases as children get older. For example, a half standard deviation increase in preschool math scores raises earnings by 2.5 percent, while a half standard deviation increase in middle childhood raises earnings by 3.5 percent. A 3.5 percent increase corresponds to about $1,200 a year in additional earnings for the average adult. Notably, girls see a greater increase in adulthood earnings from an improvement in math scores than boys – more than three-quarters of a percentage point at every life stage.

The same cannot be said for the earnings impact of improving reading scores, which actually diminishes as students get older, falling from 0.9 percent (about $300) to 0.5 percent (less than $200) from ages 5 to 11. Meanwhile, the impact of health and social relationships are consistent but modest as children get older. “It’s not an enormous impact, but it’s an impact,” Acs says. “Would you pass up a 3 percent raise?”

“It consistently shows that things you do early in life do ripple through,” he continued. “And even when you might not see a clear causal pathway,” he says, “it’s a good framework for understanding how early life stuff matters.”

The analysis bolsters previous research touting a correlation between math and earnings later in life and gives policymakers much to think over as they choose among interventions aimed at benefiting children in the short or long term, as well as when might be the most effective moment to unleash those targeted interventions.

“It is useful to see what are the curricular options and where you can intervene in kids’ lives early on if you want to have a long term impact,” Acs says. “And it does show that improvements in childhood and elementary school do matter and carry on into earnings.”

For example, Acs says, it may be worth making bigger investments in math in later grades given that improvements in middle school have a more significant impact on earnings than in preschool. And for school leaders looking to make a dent in the earnings gap between men and women, it’s important to know that increasing math scores in childhood consistently raises the adult earnings of girls by a greater percentage than those of boys – even if in absolute dollar terms, increasing math scores raises boys’ earnings, too.

In the wake of the recent “science of reading” overhaul that shifted how educators teach students to read, policymakers are increasingly setting their gaze on math pedagogy. Math achievement improved slowly between 1990 and 2013 and then plateaued, only to fall sharply during the pandemic. On average, students lost half a school year in math between 2019 and 2022. The most vulnerable students fell even further behind, exacerbating racial and socioeconomic inequities.

Recovery has been stubborn and slow. Students recorded the largest drop ever in math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress last year, falling by 9 points last year to their lowest levels in more than three decades.

“We always talk about this amazing predictive power of early mathematics,” says DeAnn Huinker, professor of math instruction at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and director of the Center for Math and Science Education Research. “And I think we’ve taken math identity and agency away from kids, and just squashed the love that you find in 3-, 4- and 5-year-olds when they’re exploring numbers. Kids just really get turned off of mathematics, so I think we’re fighting that right now.”

Education policy experts, lawmakers and business leaders agree that the nation needs to drive improvements in K-12 math to remain competitive in an increasingly technical global economy. On the most recent internationally benchmarked test, known as the PISA, Americans scored lower than students from 36 other countries. And Defense Department officials are concerned about Americans’ contempt for math, warning that it has serious implications for national security, including ceding the U.S.’s long-held technological dominance.

Looking ahead, the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the number of jobs in so-called “math occupations” is set to increase by 29% by 2031, or by roughly 30,000 jobs per year – a faster clip than for other occupations.

Though the debate over how to correct course is ongoing, experts say that the way schools are currently teaching math doesn’t work very well; further complicating the problem is the fact that many teachers who seek out positions in early elementary grades – the important foundational math years – do so because they don’t like math. Teachers should move away from procedural learning that involves rote memorization, Huinker and others say, and focus instead on conceptual understanding, which helps students recognize underlying math relationships, and developing a positive math identity.

“The number one goal is to really get at this deeper understanding of mathematics,” she says. “We want kids to make sense of the mathematical ideas that they’re exploring and learning about. So not rote learning, not memorizing, not worksheets. We do a lot that still is perhaps bad practice in early mathematics.”

Huinker says she hopes research like that from the Urban Institute’s analysis crystalizes for policymakers and school leaders the importance of getting math instruction right – especially in the early years.

“One thing that’s starting to really be more acknowledged is the importance of early mathematics and its predictive power for the long term,” she says. “There’s so much emphasis on reading and literacy, which is super important, but it kind of always overshadows mathematics. The crux of all of this early childhood, elementary and middle math is ensuring that kids feel empowered with agency to make sense of mathematics, to question, to explore, to really think of themselves as confident in that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)