Student Voice: Student, Sibling, Mentor, Mess. Pandemic Has Me Juggling Roles and Craving Sleep

“How do you spell ‘April’?” my little brother asks me. Then, throughout the day:

“Can you get me a book to read?”

“When do I get to take the bus to school again?”

“What’s a coronavirus?”

When I first learned I wouldn’t be returning to school to complete the year, I immediately felt defeated and overwhelmed. The coronavirus has not brought any hospitalizations or untimely deaths to my family. But there has been increased stress, dashed plans and little quiet.

Along with my 12-year-old sister and parents, I have to homeschool my younger brothers for the next two months and figure out a way to keep them engaged through August, since local summer programs will likely be canceled.

We rarely have 20 minutes of uninterrupted peace.

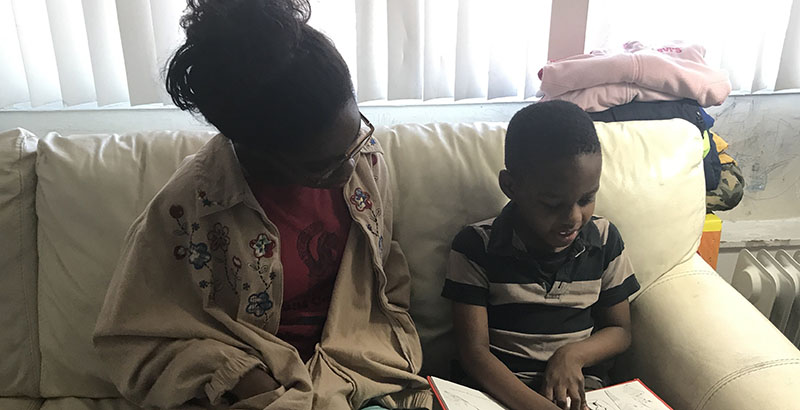

On the last day of “regular” school, my brothers came home with three packets of work and reading logs. They’ve been working their way through them while watching interactive videos sent by their teachers. At 5 and 7 years old, they’ve learned to navigate Zoom with few problems.

But they are still struggling to grasp that school is something they have to do every day, even without their teachers’ direction. At home, they play loudly, watch Nickelodeon, make messes of their meals and get into several screaming fits a day. Their hyperactivity is endless, and so is their ability to squabble over stolen toy cars and spilled juice. Countless times throughout the day, my brothers burst into the room I share with my sister, hurling accusations.

“He scratched me!”

“He hit me first! He started it!”

“I’m not your friend anymore. I’m telling on you!”

Then one or both of them dissolves into tears. Before the pandemic, I had never seen so much animosity between my brothers. But I know it’s more than them being little boys. They aren’t used to being at home all the time and interacting with each other so much; it’s making them a bit restless.

The situation offers my sister and me an opportunity to teach them conflict resolution. We lose our patience often and yell at them sometimes, but we try our best.

“Don’t pick fights, both of you,” I tell them. “When someone makes you upset, don’t hit or scratch them back. You don’t want to be angry and sad during this time. Let’s do something fun that won’t make you upset.” I try to get them to focus their energy on positive activities like reading, drawing and playing quietly.

Because of my parents’ schedules, the job of teaching my brothers typically falls to me. My dad works remotely from home. My mom spends most of the day cooking, doing laundry and housekeeping. In the mornings, she gathers food for the family from distribution locations in the city where I live, near Washington, D.C.

A few weeks before I was born, my parents immigrated to the U.S. from Ghana in search of a better life. I will be the first in my family to attend college in America. Despite my determination, I at times feel frustrated. Prior to the pandemic, I was usually able to surmount the obstacles that often accompany having immigrant parents who don’t know the U.S. education system. They understand that it’s important to get good grades. But they don’t know what a GPA is or how to navigate college admissions and scholarships. They also don’t grasp that admission to American universities isn’t based solely on academics.

I’m used to being able to find a way, despite my parents’ lack of understanding. I’m used to being in control of my academic pursuits. I plan in advance. I try to register for tests and office hours; I meet with my counselor to soak up all the free advice. But with the pandemic, stay-at-home orders and SAT cancellations, very little is currently under my control.

I look to next year’s college applications with dread. Months ago, I saw myself done with standardized testing, traveling across the country for the first time and speaking at journalism conferences on the importance of youth media. Now homebound, I stress over SAT cancellations and online AP exams.

I’ve watched friends grow disappointed when internship opportunities fell apart. NPR announced recently that it had canceled its summer internships — somber news for my hopeful friend on a gap year who was awaiting a response.

This past month has been especially chaotic. According to the Virginia Department of Education, teachers aren’t supposed to assign any new content or offer grades for the third quarter. During the closure, we’re only supposed to get optional review assignments on material we’ve already been learning. But since I’m taking five AP courses, I’ve been getting both new assignments and review material that piles up within hours. AP teachers have a lot more leeway to give assignments to students preparing for exams.

I’ve had calculus Zoom meetings outside of regular school hours and essays due on Sunday by 11:59 p.m. Trying to understand AP Physics problems online just isn’t the same, and I worry about failing the now 45-minute exam. Physics is very hands-on and application-based; the virtual labs are no substitute for in-person experiments. Online physics is much more dull and difficult, something I wouldn’t have dreamed possible before the pandemic.

At home, I never truly feel like school is over. I could be eating a meal or reading a book when I am jolted by notifications from teachers about missing assignments. In the middle of cleaning up after my brothers, I remember Zoom meetings I didn’t put on my calendar.

Online learning feels like more work than regular school because I am no longer doing assignments in isolation; homework and video calls drop in the middle of real life, which is much more exhausting. At school, I’m divorced from my family obligations; at home during a Zoom call, people constantly enter and exit my room, and my brothers inevitably burst in and distract me.

I work on my schoolwork late into the evening, usually past midnight. Like many other students, my sleep schedule has been derailed.

I’ve heard from friends who are only children about how lonely and isolated they feel. That makes me feel lucky, even in my loud and turbulent home. At times, I relax by making illustrations and practicing hand lettering. I also journal when I can.

I haven’t achieved any structure or order to my days; they are as disorganized and erratic as my thoughts. But I do try to approach this with the same mindset I’ve had since the first day of school — that is, taking things day by day.

“Pandemic Notebook” is an ongoing collection of first-person, student-written articles about what it is like to live through the coronavirus pandemic. Have an idea? Please contact Executive Editor Andrew Brownstein at [email protected].

Bridgette Adu-Wadier is a junior at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Virginia. She is an editor for her award-winning school newspaper, Theogony, and a freelance reporter for The Alexandria Gazette.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)