Student Hunger is Pervasive in Ohio

Combatting hunger means fighting stigma, ‘pride gap,’ experts say

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Student hunger looks different in every school district in Ohio, but legislative intervention could resolve the issues, from the funding gap to the stigma attached to meal support, advocates say.

Districts across the state have held fundraisers to pay down unpaid meal accounts, and alternatives to hot meals are available, often in the form of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and other cold offerings.

But combatting student hunger often comes with a “pride gap” – those that are too embarrassed to ask for help – and students who would rather not eat than face a cafeteria of students who will be able to identify their free or reduced lunch status.

Schools do what they can to make sure food is available for students, but they can’t eliminate that stigma that puts kids into “categories.”

“It still doesn’t eliminate that category of kids, it doesn’t capture hunger in totality,” said Alexis Weber, food service director for Austintown Local Schools. “Because someone’s income might not directly indicate whether or not a student is hungry.”

Hunger landscape

Food insecurity is very much a part of the landscape in Ohio, with Feeding America ranking Ohio 13th in percentage of children with food insecurity. The Children’s Defense Fund Ohio found that 1 in 6 children in Ohio “lives in a household that faces hunger,” yet 1 in 3 children in food insecure households who are eligible for the school meals program don’t participate for fear of judgment.

“The program inherently labels and puts kids into categories,” CDF-Ohio stated in a white paper on student hunger. “The stigma felt by students that the program is only for low-income kids causes many children not to participate.”

Participation in the school meals has been linked to “positive educational and health outcomes for children,” according to CDF-Ohio, and students are less likely to have “nutrient inadequacies.”

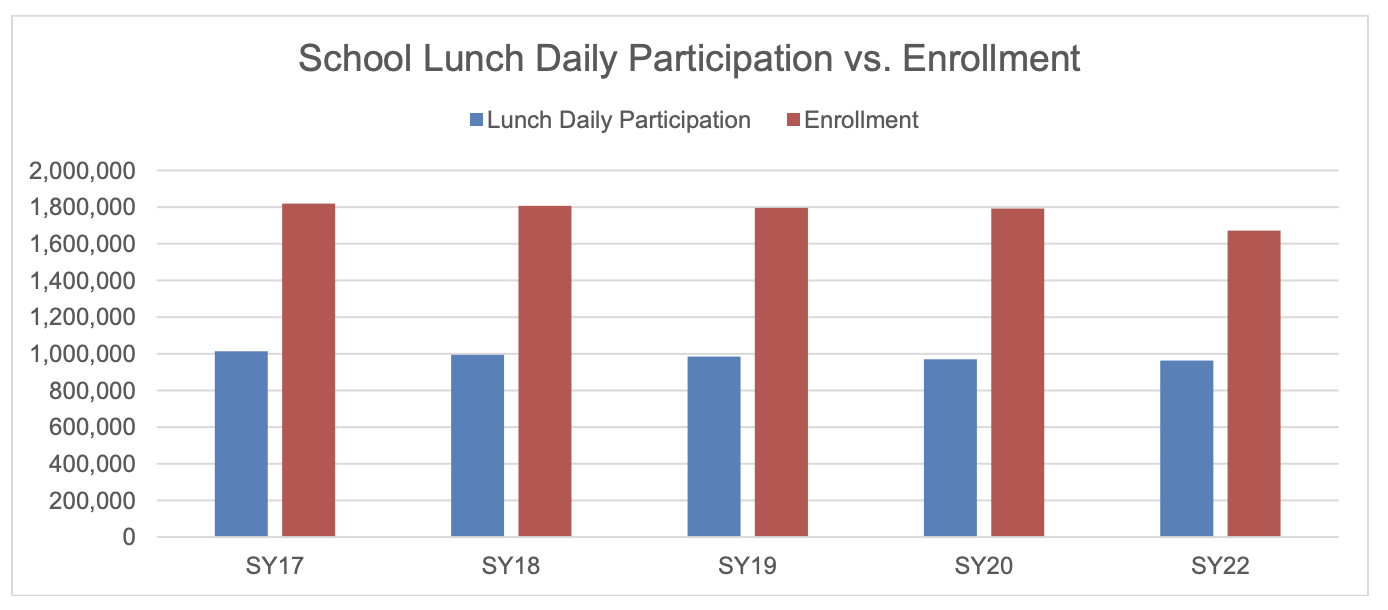

According to the Ohio Department of Education, participation in the National School Lunch Program from 2017 to 2022 has largely remained the same, even as school enrollment goes down.

In the 2021-22 school year, statewide participation in school lunch was 57.6%, up slightly from the 2019-2020 school year, when it was 54.1%. The 2020-2021 year wasn’t calculated because of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the ODE.

Free and reduced lunch programs are supported through the federal National School Lunch Program, and free breakfasts are also a part of the strategy to get children fed while they’re required to attend school. The ODE said not all schools participate in the NSLP, but of the more than 3,700 schools who do, more than 91% operate both the NSLP and the School Breakfast Program.

“These figures are increases from school year 2019-2020 (pre-pandemic),” the ODE stated in a December 2022 report.

A household is eligible for free school meals currently at 130% of the federal poverty level, meaning $36,075 or less for a family of four. For a reduced-price meal, households are eligible at 185% of the federal poverty level, or up to $51,338 for a family of four.

But a gap exists between the federal funding and district-level general funds, which school nutrition administrators have said can be filled through state investment.

School admin focus on universal meals

As budget talks continue at the Ohio Statehouse, Weber and other school food service leaders told the stories of their districts, imploring lawmakers to consider funding for universal lunches in the state, not only to reduce the hunger, but also to eliminate identification of those receiving financial help.

Chesapeake Union Exempted Village School District Superintendent Doug Hale told the Ohio House Finance Committee that the expiration in June 2022 of pandemic-era waivers that allowed schools to provide free school lunches to all students regardless of family income made Appalachian districts like his “brace themselves for the challenge to come.”

“I’m here to testify that hungry kids can not perform academically, and we have hungry children in our district,” Hale said.

What Hale also found as he worked through the challenge was that his district’s struggles weren’t unlike districts in the rest of the state.

Chesapeake’s student meal debt sits at $60,000, according to Hale. Other districts, like the Lancaster City School District and Westerville City Schools, have $40,000 in meal debts.

“I’m here to tell you that Chesapeake, Westerville and Lancaster, we serve kids, that’s as far as we’re alike,” Hale said.

In a snapshot by the Children’s Defense Fund-Ohio, the group found several schools with thousands in student meal debt, including Washington Local Schools in Lucas County ($38,000), Lorain County’s North Ridgeville City School District ($14,040), Minford Local Schools in Scioto County ($13,771), Delaware City Schools ($8,693), Alexander Local Schools ($7,000), and Wellington Exempted School District in Lorain County ($4,108).

Pickerington Schools currently has more than $46,000 in charges, according to Brent Kasler, supervisor of food services.

The stigma of free and reduced lunches, particularly in high schools, flows through rural, urban and suburban districts all the same.

“This means many high school and middle school students who need these meals go without,” Hale told the finance committee.

Hale’s testimony was bolstered by other district nutrition officials, who testified with the finance committee and its subcommittee on primary and secondary education in March.

Daryn Guarino, of the Alexander Local School District in Athens County, told the subcommittee that while the district has an alternative option for students who have a negative balance and can’t receive the hot lunch, there are students who don’t come back to the cafeteria once they’re told they can’t receive the same lunch as other students. This included a six-year-old, he said, in a situation that made him question whether he wanted to do the job.

“I’m sorry, but despite everyone’s best efforts and intentions, a student went without lunch for several days because they were ashamed that they didn’t have the money to pay for it,” Guarino told the OCJ. “Our willingness to feed them did not get them fed. I wish I were lying.”

Donating to districts

For now, donations are accepted to help pay down meal debt, typically through individual districts’ treasurer’s office.

“We usually have individuals or organizations that will contact a school about helping to pay off a student’s negative balances,” Pickerington’s Kasler told the OCJ.

Donations sent to the treasurer’s office in Pickerington are transferred to the food service account, where balances in school buildings can be paid off.

Other districts contacted by the OCJ also said financial support should be directed through district treasurer’s offices.

Ohio Capital Journal is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Ohio Capital Journal maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor David DeWitt for questions: [email protected]. Follow Ohio Capital Journal on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)