Steiner & Weisberg: When Students Go Back to School, Too Many Will Start the Year Behind. Here’s How to Catch Them Up — in Real Time

September 2020: You are a 10th-grade English Language Arts teacher in Urban City USA. Your curriculum says to teach George Orwell’s novel 1984, but half your class lacks the vocabulary and interpretive skills to read the book. So, following your training to differentiate your teaching, you ask those students to read Lois Lowry’s The Giver instead — a seventh-grade text you think they’ll be able to manage.

A version of this scene will play out in thousands of classrooms across the country this fall. Students have missed months of learning time while schools have been closed, and far more than usual will start the year behind academically. Giving those students lower-level work to help them catch up — or, in the more extreme version, asking them to repeat an entire grade — has good intentions and a certain logic. It’s also largely ineffective.

A summary of the best research shows that as a single strategy, retention basically doesn’t work. In the earlier grades, it may make a tiny initial difference that largely dissipates over time. Retaining middle school students doesn’t work at all, making them more likely to drop out of high school. And even the limited positive effects of retention seem to come from strategies that go well beyond just repeating a grade.

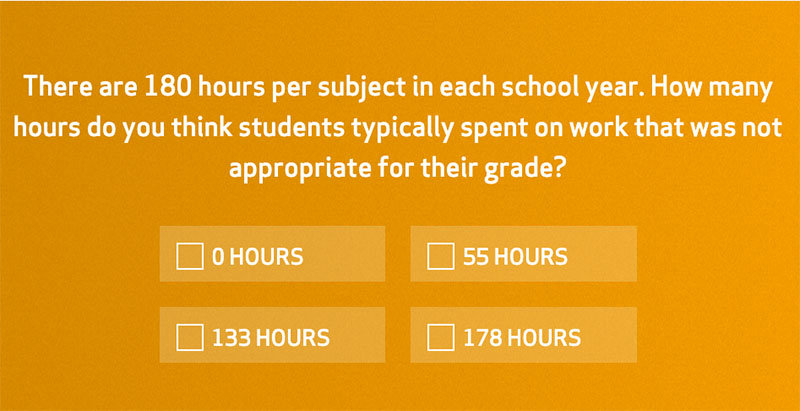

Remediation — promoting students who have fallen behind but continuing to give them work better suited for earlier grades — is a far more common approach, but just as ineffective. A recent TNTP study showed that giving students watered-down content practically guarantees they’ll lose more academic ground and get even less access to grade-level work in the future. The students stuck in this vicious cycle are disproportionately the most vulnerable: children of color, from low-income families, with special needs or learning English.

In other words, “meeting students where they are” and trying to remediate learning deficits often just results in having to meet them even further back next year. It stigmatizes students and reinforces inequities. As one critic puts it: “Reverse movement at a tedious pace with little relevance to today’s standard will not catch students up to their peers. In fact, this model may contribute to widening gaps, as stronger students get even stronger while the weaker ones continue to sink further.” A greater dose of these strategies in the coming school years will only exacerbate opportunity and achievement gaps.

Instead of delaying access to grade-level work for students who’ve fallen behind, we need to accelerate it. Imagine that instead of assigning half the class The Giver, the teacher decided that no student was going to miss out on reading 1984. That teacher would have to do focused work with the less-prepared students: They might be asked to watch the movie rendition or listen to the book on tape; they might need to review plot guides or digital editions of early chapters with embedded vocabulary help and synopses. The key is that these interventions happen just before the whole class encounters the text. Done right, they can give students who have fallen behind access to grade-level materials at the same time as their peers.

Building these “just-in-time” strategies to access grade-level content is not easy. It takes a clear understanding of what students have learned and what they haven’t (which, in turn, requires high-quality diagnostic assessments), extra planning and potentially extra instructional time before or after school. But it is possible, and it is being used successfully in schools like Concourse Village Elementary School in the Bronx and the Vanguard Academy network in South Texas.

All school systems should commit to following their lead and to planning right now for accelerating students who have fallen behind instead of remediating them. It will require big investments in providing targeted professional learning to educators this summer, including time for them to collaborate and plan. Schools will also need a smart strategy on diagnostics and robust social-emotional support for the many students who have experienced trauma during this crisis. To make it possible, the federal government will need to cushion states from the fiscal calamity that is threatening to slash education budgets.

Even in the best-case scenario, mastering an entirely new approach to catching students up will take time. That’s OK. Just trying to give every child a real chance to do grade-level work, however imperfectly, will lead to far better results than picking and choosing who gets those opportunities — right now and over the long run.

In the aftermath of this crisis, schools will have an opportunity to provide students, especially marginalized students, with far better academic experiences than they did before. It starts with a commitment to accelerating learning instead of ratcheting it ever downward.

David Steiner is director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, professor of education at Johns Hopkins University and a member of the Maryland State Board of Education. He previously served as commissioner of the New York State Education Department. Daniel Weisberg is CEO of TNTP, an education nonprofit that helps school systems across the country end educational inequality and achieve their goals for students. He previously served as chief executive for labor policy at the New York City Department of Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)