State Data: Child Care Now Unaffordable for Majority of Families

Child care is unaffordable for 85% of Virginia families with infants, according to a report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Child care is unaffordable for the majority of Virginia families with young children and nearly all low-income families with young children, a study by the state’s legislative watchdog found.

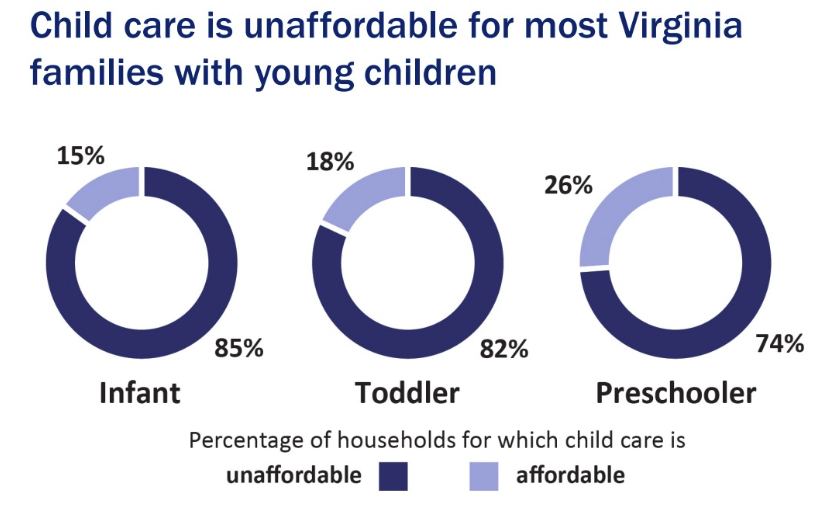

According to the report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, child care is unaffordable for 85% of Virginia families with infants, 82% of families with toddlers and 74% of families with preschoolers.

Those percentages are even higher among low-income Virginians, with child care being unaffordable for 98% of families with infants, 98% of families with toddlers and 97% of families with preschoolers.

Infants are generally defined as children ages 0 to 15 months, with toddlers ages 16 to 23 months and preschoolers ages 2 to 4 years.

“Recent literature indicates that without child care, parents are often forced to reduce their work hours, take lower-level or lower-paying jobs or drop out of the workforce altogether,” said Stefanie Papps, a JLARC staffer who led the study, during a presentation Monday. “Although this can be a significant barrier to self-sufficiency for lower-income families, lack of affordable child care can be a significant barrier to employment for any family.”

In arriving at those figures, JLARC relied on the federal government’s definition that child care is unaffordable if it costs more than 7% of household income.

“In some areas of the country, including the Northeast and South, child care can be a family’s largest household expense — more expensive than even their rent or mortgage,” the commission wrote.

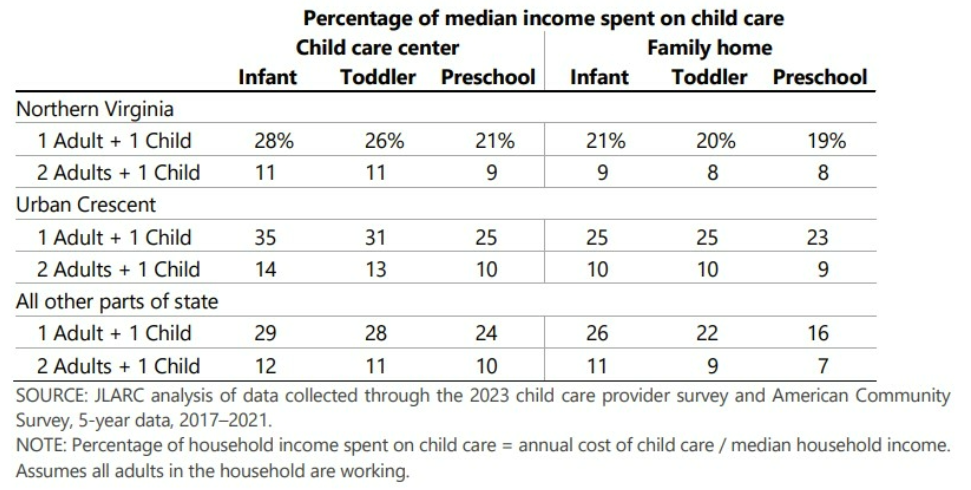

Statewide, researchers found Virginia families spend $100 to $440 per week, per child on care, with the highest expenses found in Northern Virginia. Care is generally most expensive when children are youngest, both because parents tend to be younger and earning less pay and because required staffing ratios at licensed facilities are higher for younger children, who need more intensive care and supervision.

“Annual incomes need to be approximately 13 to 38 percent higher to afford care for infants and toddlers in child care centers, depending on the region of the state,” JLARC wrote. “These incomes would be necessary to afford care for one child; higher incomes would be needed to afford care for more than one child.”

The situation could worsen. Pandemic-era expansions to a federal child care subsidy program expired this Sept. 30, and an additional $15 billion in child care grants to states that target low-income families is set to end Sept. 30, 2024. Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Virginia, has previously warned the end of the expanded subsidies could cause 80,000 children in the commonwealth to lose their child care slots, in line with estimates by the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank. JLARC on Monday put the figure at 25,000 children.

The commission concluded it would cost the state almost $320 million annually to extend all of the pandemic-era expansions.

“There’s a significant gap between available funding and funding that’s needed to continue to meet family demand for child care,” said Sen. Mamie Locke, D-Hampton, during Monday’s meeting. “So it falls to the General Assembly to meet this demand.”

Del. Barry Knight, R-Virginia Beach and chair of the House Appropriations Committee, said lawmakers “knew it wasn’t going to last” and noted that Virginia’s Democratic Sens. Kaine and Mark Warner “understand this is a problem.”

“They’re the ones who kind of put a mandate on the state of Virginia, because they, Congress, gave us this money to help us in a time when we needed help,” he said. “Sometimes it’s hard to fund the problem and pull the plug on it.”

In an Oct. 10 letter in response to JLARC’s findings, Virginia Secretary of Health and Human Services John Littel wrote that the impending drop in child care subsidy funding “should receive a disproportionate share of attention.”

Littel further said it was “imperative” that Virginia “analyze the full ecosystem of child care programming” and “facilitate a more extensive dialogue around solutions that address the full spectrum of cost-driving factors.”

“This review must include reducing regulatory burdens that impede flexibility and fostering discussions about private sector innovation to build sustainable capacity,” he wrote. “Additionally, increasing home-based care options and expanding opportunities provided by houses of worship and other community partners will be critical to expanding choices for families.”

While JLARC found that regulations do influence child care costs, it concluded that “most of Virginia’s regulations appear appropriate.”

On Monday, Papps said that staffing ratios — the number of children a child care worker is allowed to oversee — are the most significant regulation impacting costs.

“However, when compared to staffing ratios in other states, Virginia’s ratios were relatively similar to ratios in other states,” she said.

Currently, Virginia requires licensed providers to have one staff member for every four infants, every five toddlers or every eight to 10 preschoolers. Amendments to the state budget temporarily relaxed those ratios for centers that participate in the federal subsidy program through June 30, 2024 in an effort to help with staffing shortages.

A JLARC survey of child care providers found that most “do not believe that regulations seem too stringent or not stringent enough.”

“Just one-third of providers reported at least some regulations are too stringent,” the commission wrote. “Further, most child care providers and other relevant stakeholders interviewed reported that the state’s regulations seem appropriate to maintain children’s health and safety, and the staffing ratios create manageable working conditions.”

However, the commission noted that Virginia’s background check requirements are stricter than those in other states and federal guidance, and that materials included in required staff training aren’t always relevant.

Papps pointed to staffing challenges as “the root of the child care access and affordability issue.”

“Child care workers are generally earning relatively low wages — wages that would put many of these workers below the self-sufficiency standard,” she said. JLARC found that on average, “lead teachers” in child care centers earned $16 per hour in fall 2022, while assistants earned $13 per hour.

“Higher compensation leads to more staff, increasing the availability of care but increasing the cost and decreasing the affordability of care,” Papps said. “Lower compensation decreases operating costs, lowering the cost of care paid by parents, but can lead to staffing shortages that limit providers’ capacity.”

Del. Bobby Orrock, R-Spotsylvania, called the situation “a catch-22.”

“In order to have more availability, you’re going to have to increase the cost, ergo making it less affordable,” he said. “So y’all’s recommendation is: ‘Good luck.’ ”

Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Sarah Vogelsong for questions: [email protected]. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)