Some Private Schools That May Benefit From Trump’s Voucher Plan Are Weak on Discrimination Rules

But expanding private school choice — which DeVos has long championed — could send public dollars to private schools that, unlike traditional public or charter schools, are often free from rules prohibiting discrimination against students based on religion, sexual orientation, gender or disability status.

A recent study of voucher laws found that while most states explicitly prohibit discrimination based on race and national origin, only one does so based on gender, and two based on religion. None of the 25 voucher programs studied prohibit discrimination against students on the basis of sexual orientation. Some programs are meant to benefit students with disabilities, but of those that aren’t, six do not require schools to provide services to students with special needs.

In some states — including Indiana, Georgia and North Carolina — some private schools that participate in publicly funded choice programs have explicitly anti-gay policies.

An estimated 400,000 students use school vouchers or programs like them, which represent just a small segment of school choice programs across the country — there are roughly 2.5 million students attending charter schools — and a sliver of the 50.4 million students enrolled in K-12 nationally. That number could grow under Trump’s $20 billion proposal to expand school choice, including through vouchers. That has some student advocates worried while also sparking a debate in school choice circles over whether the federal government will regulate how private schools are run.

“We are very concerned when public funds are used to support a school that could blatantly discriminate against and pose potential damage to LGBTQ students, or any students,” said Emily Greytak, of GLSEN, which champions LGBTQ issues in K-12 and advocates for fair treatment of students in school regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. “Instead, public funds should be used to ensure that all schools are safe environments and provide equal access to education to all students.”

Lauren Maddox, a Trump transition spokesperson, said DeVos also wants to create schools that are safe for students and meet their educational needs.

“For nearly 30 years, Betsy DeVos has been a strong voice for parents, who simply want the right to enroll their children in learning environments that fit their unique needs and where all students are safe to learn and thrive,” she said.

A national voucher program of the sort proposed by Trump could, in theory, open private schools to more regulation, including federal attempts to curtail discrimination, similar to those enforced against colleges and universities that accept federal funding. This has stoked fear among conservative school choice supporters who worry that private schools will lose their autonomy and ability to promote certain values, including opposition to same-sex relationships.

Congress could determine what types of anti-discrimination provisions might be included in a national school voucher program. Last year, a rule to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in Washington, D.C.’s federally authorized voucher program was voted down in Congress. Supporters argued that public dollars should not fund discrimination while opponents said the proposal was a last-minute change to a program that was working well. D.C.’s system already bars participating schools from discriminating “on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion or sex.”

If anti-discrimination rules were put in place nationally, enforcement would fall on the Department of Education, which Betsy DeVos may soon head. The American Federation for Children, an advocacy group DeVos founded to promote school choice, has promoted laws that lack extensive anti-discrimination rules.

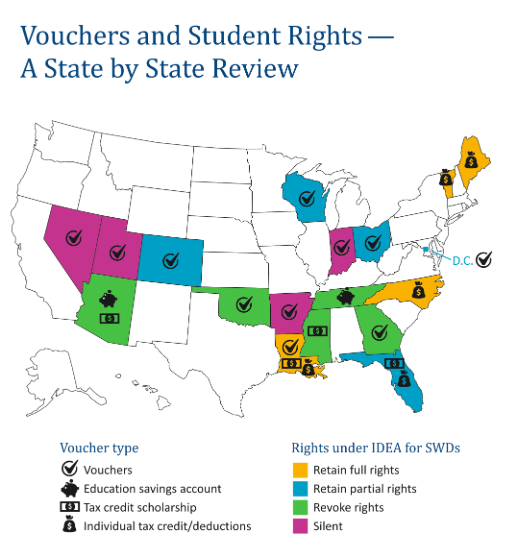

The research published last year on 25 voucher or education savings account programs across 15 states concluded that “legislators appear to have neglected to construct policies that safeguard student access and ensure public funds do not support discriminatory practices.” The study appeared in the peer-reviewed Peabody Journal of Education and was titled “Dollars to Discriminate: The (Un)intended Consequences of School Vouchers.”

There are 59 private school choice programs currently operating across 28 states, according to the advocacy group EdChoice. They include vouchers, which provide public funds for parents to pay private tuition, and tax credits, which give tax breaks to businesses and individuals who donate to scholarship funds that students can then use for private school tuition. More recently, some states have promoted education savings accounts, which provide public money for families to spend on a range of educational needs, including private school tuition.

Some of these programs are meant to benefit low-income students, those in foster care or from military families, Native American or disabled students or those attending low-performing traditional public schools. Nevada passed the first-ever universal education savings accounts, but its funding mechanism was struck down in court last year.

The Peabody study examines voucher and savings account programs but does not look at tax credits, which may be the preferred avenue for the Trump administration promoting choice.

Religion is a significant factor in most states’ voucher programs because two in three private schools in the U.S. claim a religious affiliation, the vast majority of them Christian. In Milwaukee’s voucher program, nearly 90 percent of participating schools are religious; in D.C., about 80 percent of students use the voucher for a religious institution. In Florida, the largest recipient of tax credit scholarships is an ultra-Orthodox Jewish school in Miami.

Most voucher programs allow private schools to maintain rules relating to religion, such as standards for behavior or requirements of religious affiliation. Only Wisconsin’s voucher system ensures that students can opt out of religious activities, while two programs, in Maine and Vermont, prohibit religious schools from receiving funds altogether.

Some programs — including Indiana’s and Louisiana’s systems — prohibit schools from practicing selective admission, but others allow private schools that participate to set their own admissions criteria.

Though programs in some states are designed exclusively for students with disabilities, private schools that receive vouchers in several states are not required to provide educational services specifically for special needs students.

In DeVos’s confirmation hearing, Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine asked, “Should all schools receiving governmental funding be required to meet the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act?”

DeVos responded, “I think they already are.”

That’s true for schools receiving federal dollars, but not necessarily state money through choice programs. In some cases, in order to receive a voucher, families must waive students’ rights under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

“Unfortunately,” said Susan Henderson, head of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, “most voucher or school choice programs have one thing in common: a loss of civil rights for children with disabilities.”

The federal government recently investigated the Milwaukee voucher program for under-enrolling students with disabilities, based on the American with Disabilities Act. However, the investigation was closed last year after Wisconsin created a voucher program specifically meant for students with disabilities.

Cleveland’s voucher program explicitly allows participating schools to “deny admission to any separately educated student with a disability.”

Mike Petrilli, head of the Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank, said in some cases, schools aren’t capable of addressing students’ special needs.

“We’ve learned in both the district and the charter sector that any one school, it’s very hard for them to be equipped to deal with every type of disability,” he said.

A review by The 74 of a handful of schools that participate in Indiana’s voucher program found multiple examples of anti-gay policies.

The handbook at Blackhawk Christian School in Fort Wayne, for example, states, “On those occasions in which the atmosphere or conduct within a particular home is counter to or in opposition to the Biblical lifestyle the school teaches, the school reserves the right, within its sole discretion, to refuse admission of an applicant or to discontinue enrollment of a student. This includes, but is not necessarily limited to, living in, condoning, or supporting sexual immorality; practicing a homosexual lifestyle or alternative gender identity, promoting such practices, or otherwise having the inability to support the moral principles of the school.”

Lakewood Park Christian School states on its website, “We believe that any form of sexual immorality (including, but not limited to, adultery, fornication, homosexual behavior, bisexual conduct, bestiality, incest, and use of pornography) is sinful and offensive to God.” The student handbook says discipline will be applied for “sexuality immorality,” noting that “if a child begins to live, or is living an active, unbiblical lifestyle, the school reserves the right to remove the student.”

A thorough review of Georgia’s tax credit scholarship in 2013 by the Southern Education Foundation found that nearly one in four participating schools had explicit anti-gay policies.

“This type of school … sends a strong message that [LGBTQ] students are not welcome, that these students are not natural," said Greytak, of GLSEN.

Petrilli said by its nature, private school choice programs will involve schools that set policies based on their own belief systems.

“If you support private school choice, then you have to be comfortable with allowing private schools to remain private,” he said. “One part of that is allowing them to be religious, to have a set of values they believe in, and to have an admissions process to make sure kids are a good fit for their program.”

Many private religious schools do place faith-based requirements on students.

Kimberly Quick of the Century Foundation documented one school receiving money through North Carolina’s voucher program that explicitly bans non-Christians as well as students who are “Catholic, Mormon, Jehovah’s Witness, Seventh Day Adventist, Christian Science.” The school, in Graham, N.C., also requires students to sign a form promising to abstain from “homosexual/bisexual behaviors, or any other biblical violation of the unique roles of males and females.” A school in Fayetteville mandates that students regularly attend “a local faith based, Bible believing church.”

Greytak said “private religious schools tend to be the most hostile” and least supportive of LGBTQ students but noted that there are religious schools that are exceptions in this regard.

If Betsy DeVos and Donald Trump successfully enact the campaign’s promised $20 billion voucher program, federal funds could flow toward private schools that may practice discrimination.

On the other hand, getting the feds involved may help limit discrimination since federal civil rights law applies to educational institutions that receive public funds. Colleges and universities are bound by federal civil rights law, including Title IX’s ban on sex discrimination, which courts have interpreted to include sexual orientation.1 These sorts of regulations have caused a handful of conservative or religious colleges to decline federal dollars, though a few dozen other schools have received religious exemptions.

Recently, social conservatives have complained about what they see as overreach from the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, including rules ensuring that transgender students can use the bathroom of their identified gender, a move that is currently before the Supreme Court.

This scenario is exactly what some conservative critics fear — D.C.-based regulations infringing on the autonomy of religious schools, which will be unable to resist the siren song of federal money.

Writing in The Federalist, Joy Pullman suggests that a federal voucher program would “nationalize” education and criticizes the Obama administration rules on bathroom access, saying the education department’s “Office [for] Civil Rights has essentially gone rogue on this regulation and many others under the Obama administration, going [so] far as to demand that religious schools that accept federal funds repudiate their religion over it (an ominous development that overshadows talk of federal vouchers).”

A survey released by the Fordham Institute found that many private school leaders said that maintaining admissions discretion was crucial to their school, and that rules against that might lead them not to participate in voucher programs.

“The reason that many supporters of private school choice don’t want the federal government anywhere near this issue is because they worry that it will lead to greater regulation, micromanagement, [and] limits on these kinds of choice programs,” Petrilli said.

And of course, public schools are hardly free from discrimination or bullying, as GLSEN has extensively documented, and certain private schools may provide more welcoming experiences for students. An Atlanta private school, known as the Pride School, opened in September, catering specifically to LGBTQ students. A voucher could make such a school — which charges $13,500 a year in tuition — available to students who otherwise could not afford it.

When asked about it at the hearing, DeVos said she does not believe in conversation therapy, saying, “I embrace equality, and I firmly believe in the intrinsic value of each individual.”

She also stated that it was a “clerical error” that tax forms listed her as vice president of her mother’s foundation for more than a decade. The foundation has donated heavily to anti-gay causes in arch-conservative groups, including the Family Research Council, which the Southern Poverty Law Center has labeled a hate group.

A letter from openly gay members of Congress to Senate education committee members said, “Betsy DeVos’ career has been marked by repeated attempts to undermine the rights of the LGBT community.”

DeVos said during the hearing that people might not be drawing a distinction between her donations and those of her larger family. Supporters point out that DeVos called for the resignation of a Michigan Republican after he made anti-gay statements. A political adviser to DeVos said she defended him from attacks over his sexual orientation.

As to her position on civil rights enforcement by the DOE, Politico published an item January 6 citing an unnamed aide to Republican Sen. James Lankford saying that DeVos talked to Lankford “about reining in the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights.” At the hearing, DeVos said she had not used that language.

The American Federation for Children, the school choice advocacy group that DeVos led for years, was critical of the federal investigation into whether Wisconsin’s voucher program discriminated against students with disabilities, saying the probe was politically motivated. AFC has also promoted laws in states — like Georgia, North Carolina and Indiana — where it was later shown that some schools discriminated against gay students.

A spokesperson for AFC did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The group has produced model school choice legislation that calls for ensuring that participating private schools comply with federal law prohibiting discrimination based on race, and disability if schools receive federal funds. But AFC’s model law is silent on the issue of discrimination against students based on gender, sexual orientation and religion.

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provided funding to The 74 from 2014 to 2016. Campbell Brown serves on the boards of both The 74 and the American Federation for Children, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos. Brown played no part in the reporting or editing of this article.

1. The federally authorized D.C. voucher program prohibits discrimination against program participants or applicants “on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, or sex,” which is a relatively broad set of prohibitions, compared to other voucher programs. However, religious schools are exempted from the prohibition on sex discrimination if it violates their religious beliefs. Religious schools are also exempt from aspects of federal civil rights laws pertaining to discrimination in hiring. (return to story)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)