Senate Rewrites NCLB, Leaders Hail it as Historic Fix That Still Protects Vulnerable Students

The Senate approved a No Child Left Behind rewrite Thursday — eight years late but in a way that leaders said would fix a flawed law while not giving up on accountability standards.

The new Senate bill governing the nation’s K-12 education system — now called the Every Child Achieves Act — passed by a wide margin of 81 to 17. The vote came 13 years after the passage of No Child Left Behind and eight years after that law meant to force changes upon failing schools was supposed to be reauthorized.

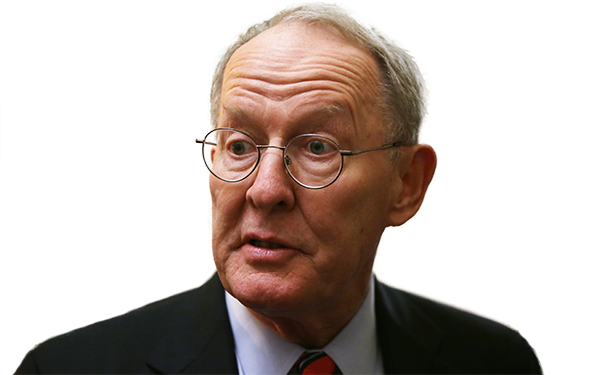

“This is a law that everybody wants fixed, we have a consensus on that,” Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., chairman of the Education Committee, said before its passage. “Everybody wants this law fixed. If you vote no, we fix nothing … This is the most important step in that direction we’ve had in 25 years.”

The new bill removes one-size-fits-all interventions for low-performing schools, gets rid of what’s called adequate yearly progress benchmarks and ends federal mandates on teacher qualifications.

Its passage is a remarkable event in federal education policy, and a testament to the deal-making skills of Alexander and ranking Democrat Patty Murray of Washington state who promised she was not giving up on school equity for the country’s most disadvantaged students.

“This is a good bill. I will keep working, of course, to make it better,” she said. “I will continue to push to strengthen the accountability measures in our bill and address inequality in our schools.”

Still, about a half-dozen Democrats voted against ending debate on the bill, and three voted against final passage of the measure, concerned that it did not have sufficient accountability guidelines.

In the coming weeks, legislators will move to conference as they work out a deal with the House, where a much more conservative, hands-off bill narrowly passed last week.

A big part of getting enough senators on board to pass a bill was coming to an agreement on Title I funding. North Carolina Senator Richard Burr had proposed tweaking the current formula, which gives more money to states with large pockets of poverty and those that spend more on education, to a formula that multiplies the number of poor children by the average per-pupil spending.

That proposal was a deal-breaker for about three dozen senators from the states, mostly in the Northeast, that would lose millions as funding shifted to states in the South and West.

Instead, senators agreed to continue using the old formula until annual Title I spending hits $17 billion – which Burr said isn’t likely for another 10 years – and then allocate new funds via Burr’s proposal.

The amendment was adopted, 59 to 39, but many members continued to oppose it.

“The impact is still severe,” said Ohio Republican Rob Portman. “It’s telling states that invest in children, you’re going to be penalized. That’s not what this body ought to be doing.”

Members from states set to lose money also voiced concerns that the funding compromise be included in the final compromise, which both Murray and Alexander pledged to do.

Photo by Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)