Schools Are Open, But Cleveland Kids Keep Cutting Class: Chronic Absenteeism Is More Than Double Pre-Pandemic Levels

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The Cleveland school district has mostly returned to normal this fall after thousands of students vanished during the pandemic last academic year, but a big aftershock has officials worried — twice as many students are skipping class than before COVID hit.

Nearly half of Cleveland’s students, 47%, are on pace to be chronically absent so far this school year. Citing pandemic stress, not feeling supported and being scared of COVID among the reasons they’ve been skipping class, students have missed 10% or more of class in the first seven weeks of school.

“We’re seeing larger numbers of that by kids who already had a larger COVID impact than a lot of their more wealthy peers,” said district CEO Eric Gordon. “Yeah, I’m concerned.”

It’s not quite as bad as during the 2020-21 pandemic year, when 54 percent of Cleveland kids were chronically absent — missing 18 days of school or more — even while classes were remote.

But the chronic absenteeism rate this fall is more than double the district’s 22% three-year average.

Gordon, who has made reducing chronic absenteeism a major goal over the last several years, said students have much lower math and reading test scores if they miss even 10 days or more of school in a year and are 30% less likely to graduate. The absenteeism numbers this fall have him worried.

“The pattern is looking more like last year than it looked like pre-COVID,” he continued. “We’re seeing lots more students with off-track behavior.”

Cleveland’s release of enrollment and absenteeism data for this school year is unusual compared to other school districts around the country, which have yet to make such data available. The 21-22 stats from the Ohio district, where classes started in mid-August, allows Cleveland officials to see trends sooner than other districts that wait until late August or after Labor Day.

As a result, states and districts around the country have been reporting details of absenteeism from last school year and its impact on students.

A notable exception is California, where chronic absenteeism has increased this school year in many districts. Oakland schools, for example, report having 17% of students chronically absent pre-COVID, 20% last school year and 33% this year.

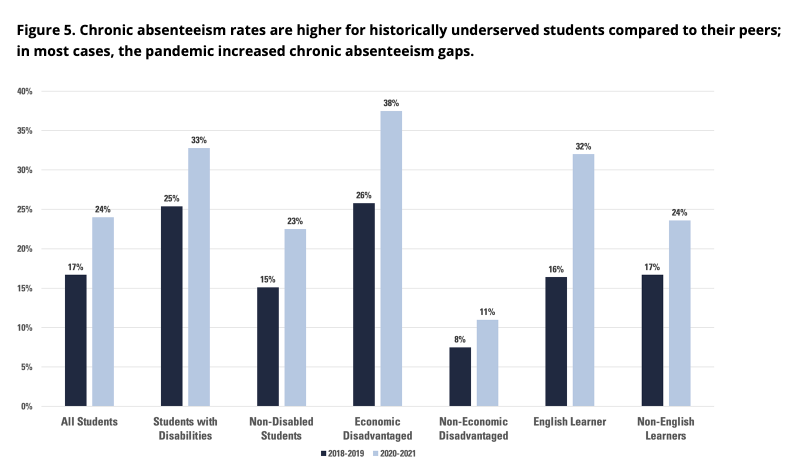

Ohio reported in September that chronic absenteeism rose from 17% statewide in 2018-19 to 24% last school year. It was a problem that hit “economically disadvantaged” students across the state hard, rising from 26% statewide to 38%, but barely affected non-poor students. Their chronic absenteeism rate rose only from 8% to 11% last school year.

Shari Obrenski, president of the Cleveland Teachers Union, said teachers have noticed that students, after attending remote classes for almost all of last year, just aren’t back at school every day.

“Going back to school five days a week seems to be difficult for some of our students,” Obrenski said. “They were out for a period of time. It’s going to take a while to get a level of stamina where kids are used to being in school five days a week.”

Overall attendance continues to be down this fall from pre-pandemic levels — 84.5% so far this school year, compared to a three-year average of 93.1%. Last year, with classes mostly online, attendance was 81.3%.

Gordon recently asked his Student Advisory Committee – a group he created with representatives from every district high school – why students were skipping class. He polled about 160 students (one from each grade in the district’s 40 high schools) for answers.

Here’s what each said was the main reason for peers skipping school:

- 21% ‐ Pandemic Stress (mental and/or physical stress)

- 18% ‐ Not feeling supported as a student (challenges with mental health and/or responsibilities)

- 16% ‐ Scared of getting COVID

- 11% ‐ Unmotivated or feeling lazy

Gordon said he’ll use these results to find ways to draw kids to class. He just isn’t sure what those will be yet.

“The behavior’s different now,” he said. “So the strategies we used before aren’t necessarily going to work.”

The district and Cleveland Teachers Union have already tried traditional tactics such as calling and emailing families of missing students to press them to return. Using a $150,000 grant from the American Federation of teachers, the union paid teachers to call families starting in July.

Obrenski said teachers reached parents of thousands of students who had skipped school last school year and drew many back, though how many is unclear.

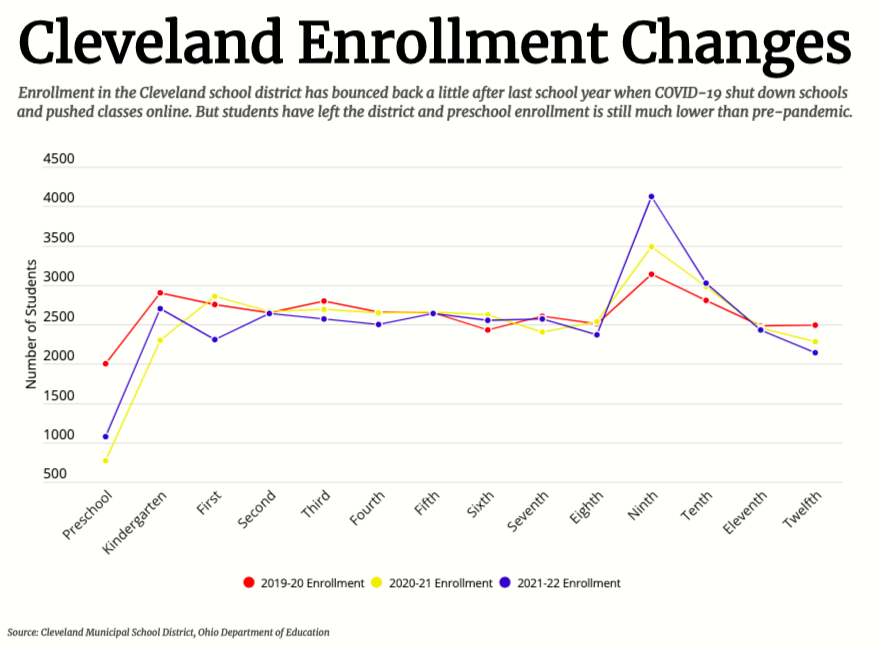

After seeing enrollment drop about 1,500 students last year, the district has regained close to 300 this school year. That still leaves the district with about 35,600 students, more than 1,200 fewer than the 36,800 in 2019-20.

The bulk of the loss comes from preschool students, who have dropped from an enrollment of about 2,000 in 2019-20, pre-pandemic, to about 1,100 this year. Preschool is not legally required by the state, so parents don’t have to enroll their children.

“We’re still in the pandemic,” Obrenski said. “Families are still cautious about putting their children in in-person school situations.”

Katie Kelley, head of the PRE4CLE citywide preschool expansion effort, said preschools across Cleveland, both public and private, are still well below pre-COVID enrollments.

“Certainly the delta variant made a more complicated return to school, with many families reluctant to return their children to group settings,” she said.

Kindergarten, first grade and third grade are all down more than 200 students each. High school seniors fell by nearly 350 students.

But there is also nearly a 33% gain — almost 1,000 students — in ninth graders. District officials say part of that comes from opening two new high school buildings, one replacing the deteriorating John F. Kennedy High School built in 1965.

Obrenski also credits the 2020 launch of the Say Yes to Education college scholarship program in the city, which requires students to attend district high schools or partnering charter schools all four years to qualify.

“If they’re not in a district high school, they’re not getting scholarship dollars,” she said.

How much of the 1,200-student drop is from students moving to parochial or charter schools is also still unclear. State data with those details is still unavailable. But Gordon said early data he’s seen suggest few have just dropped out of school altogether.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)