School Reopening Plans Fuel Fears of Teacher ‘Brain Drain’ — and Trump’s Threats Aren’t Helping

Surging coronavirus rates have already turned the politics of bright-red Texas upside down: Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, who in April barred local governments from requiring face masks, this month ordered that masks be worn statewide.

The virus is turning schools there upside down too.

When the Texas American Federation of Teachers put a call out last week for an informational webinar on family and medical leave, disability claims and retirement, 4,000 people signed up.

“We don’t want people to retire,” said Rob D’Amico, the union’s communications director. But he admitted that as schools prepare to reopen — often under political pressure — teachers and other school workers, who are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to close conditions in schools and many teachers’ advanced age, may not necessarily cooperate. With infections raging statewide, he said, the school staffing picture is “a nightmare.”

As in states elsewhere, surveys of the union’s members show that most don’t want to go back to school until they feel it’s safe. As a result, even if schools nationwide open on time and offer in-person instruction, families may need to get used to new faces, since a large proportion of our teachers and principals simply may not return.

“I love teaching,” said a 53-year-old north Texas middle school math teacher who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisal. “I’ve been in education for 30 years, almost. I went to school for it. I knew that was what I was supposed to be: a math teacher. I knew. I still love it. But I’m scared to death right now.”

Teachers in her district are due to report to work on Aug. 6, with students returning on Aug. 17, though on Tuesday Gov. Abbott indicated he would extend the time in which schools could continue with online-only instruction, saying it’s “a local-level decision.” But so far she has little faith that district leaders have thought through the possibilities. What happens, for instance, if a student falls ill? Does the entire school close for five days to be sanitized?

What if a teacher calls in sick with COVID-19? Does the district call in a substitute teacher? “We already have a hard time getting substitutes in middle school,” she said. “Do you think there’s a substitute that’s going to take my place for two weeks, after I’ve gone out with this disease?”

And if there’s a breakout in her classroom, she said, would anyone even set foot in it?

“I would love to teach four or five more years,” she said. “… But right now it’s a little bit scary.”

In Florida, which is seeing record-high numbers of new cases, veteran Orlando reading teacher Mark Noel said he’s also trying to figure out what to do this fall. Noel, who also coaches tennis at Oak Ridge High School, said two of his seven players have tested positive for coronavirus in the past two weeks. “Can you imagine football teams that are conditioning right now? How many are infected? Do we send them to the classroom?”

Wendy Doromal, president of the Orange County Classroom Teachers Association in Florida, said teachers are “panicked and terrified.” In a few cases they’re simply quitting outright. She said dozens of teachers have resigned as others scramble for information on retirement, sabbaticals and Family and Medical Leave Act policies.

Richard Corcoran, Florida’s education commissioner, this month issued an emergency order requiring schools to open at least five days per week. Doromal said the union has asked the district to push its start date to the last day of August, noting that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended 14 consecutive days of a decline in COVID-19 cases before restarting mass gatherings. “Certainly a surge is not a decline,” she said.

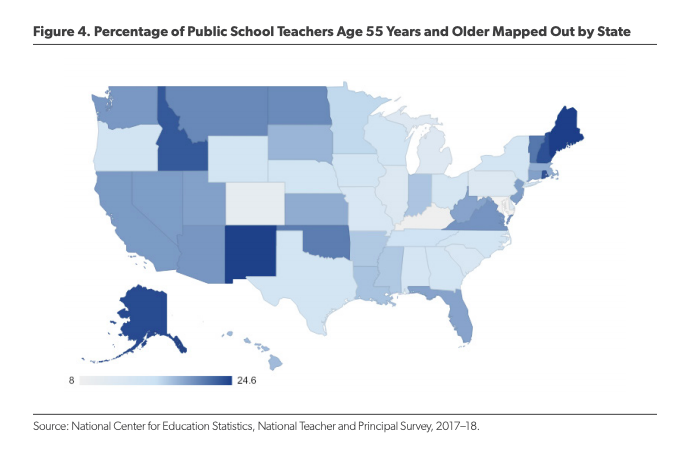

Educators are a particularly vulnerable group of workers, mostly because of their age: When the American Enterprise Institute last spring examined U.S. school demographics using federal data, it found that more than 18 percent of public and private school teachers and 27 percent of principals are older than age 55, putting them in the “most at-risk age range” for COVID-19. Workers at private schools may actually be in greater peril: About 25 percent of private school teachers and 44 percent of principals are at risk.

Overall, AEI found, nearly 646,000 public and private school teachers are older than 55.

In 20 states, AEI found, at least 20 percent of teachers are 55 or older. Those include a few of the largest states, and those with the highest infection rates: In California, Florida, Texas and Arizona, with some of the most dramatic rises in recent COVID-19 cases, a combined 154,637 teachers were 55 or older, according to the data.

‘No, thank you’

“A lot of administrators and teachers who are eligible to retire will retire,” said Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators. “Why take the chance of being in an environment that, even under the best of circumstances, is still a risk?”

Domenech, a former superintendent of Fairfax County, Virginia, Public Schools, said the issue took on added resonance last week when Trump administration officials — including the president himself — ratcheted up pressure on schools to reopen with in-person instruction.

“We want to reopen the schools,” Trump said. “Everybody wants it. The moms want it, the dads want it, the kids want it. It’s time to do it.” Schools that don’t open before the Nov. 3 presidential election, he tweeted, may risk losing federal funding.

Speaking to governors during a conference call, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said she expects schools to be “fully operational” this fall, regardless of the size of the pandemic. DeVos on Sunday told CNN, “I think the go-to needs to be kids in school, in person, in the classroom.” She said “little flare-ups or hot spots” of the disease can be dealt with “on a school-by-school or a case-by-case basis.”

Domenech predicted that Trump and DeVos’s demands won’t fill educators with confidence. “You’re going to see a greater number of staff saying, ‘In this kind of environment? No, thank you. I’m not going to put myself at risk.’”

He said Trump’s ultimatum is empty — Congress controls virtually all of the purse strings on federal education funding, with the exception of small grants overseen by the U.S. Department of Education.

“It’s bluster,” Domenech said. “That bullying is not going to work here. We’re very familiar with bullying in schools.”

But the threat itself could be consequential, said American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten. “His recklessness threw a monkey wrench, to the extent that I am really afraid today that there’s going to be a brain drain, and that people are going to leave and people are not going to come back.”

In light of Trump’s push to open schools no matter what, Weingarten said, “a lot of people will start thinking about: Can they retire? Should they take a year off? Should they ask for a reasonable accommodation?”

Warning signs

Schools nationwide moved quickly to close down last spring once the coronavirus took hold, but it had already wreaked havoc on workers. Education Week for months has maintained an Educators We’ve Lost to the Coronavirus memorial page that by last week had honored more than 350 people.

Already this summer, warning signs are blinking for educators.

- In California’s Santa Clara County, 45 principals and other administrators were ordered to quarantine after an attendee at a late June school district meeting tested positive for coronavirus. Officials had called the meeting so they could discuss fall reopening plans.

- In Missouri, a Christian summer camp shut down last week after more than 80 campers and staff tested positive for coronavirus, health officials said.

- In Arizona, a 61-year-old first-grade teacher died of COVID-19 in late June after she and two colleagues who taught in the same classroom contracted the disease.

Meanwhile, Americans are divided about schools reopening.

A Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll released in early June showed a split among voters on sending children back to school or day care in August. Among parents of children under age 18, 48 percent were comfortable with the idea, but with divides by political affiliation.

And teachers and principals also are not particularly sanguine about returning to full-time, face-to-face instruction in a few weeks.

In an Education Week survey conducted in late May, two-thirds of educators said they were “concerned about the health implications of resuming in-person instruction in the fall,” with 1 in 5 saying they were “somewhat more” or “much more” likely to leave classroom teaching at the end of the school year. Before the coronavirus outbreak, fewer than half as many said they were likely to leave teaching.

Overall, the survey found, 44 percent said they had colleagues who were now likely to leave classroom teaching. Perhaps as a result, several large districts, including Los Angeles, San Diego, Atlanta and Nashville, will begin the school year entirely online.

Educators’ confidence in their workplaces’ ability to prepare for the fall term is decidedly mixed. If strict cleaning, mask-wearing and social-distancing guidelines are followed, teachers seem supportive of returning to school buildings: An American Federation of Teachers survey in June found that 94 percent of members endorsed standards by which schools would reopen with “daily deep cleaning and sanitizing of school facilities.” And 92 percent endorsed protective personal equipment (PPE) and training for staff and students.

In Chicago, the city’s teachers union last week said about 40 percent of its members believe in-classroom instruction shouldn’t resume until a COVID-19 vaccine is widely available — even if that takes a year.

Weingarten, the AFT president, said teachers, especially older ones, are reluctant to risk their health: “If you’re a teacher in your 50s or your 60s and you’re taking care of an elderly parent, how do you go back to school?”

Roberto Rodríguez, president and CEO of Teach Plus, a nonprofit that works on policy and leadership issues with teachers in 11 states, noted the obvious: Most teachers actually prefer face-to-face interactions and are eager to get back into the classroom. But they worry about the uncertainty that awaits them there.

“A lot of the classical training of our teachers is about building the trust and the social and interpersonal connections in relationships with students that are the foundation for how they learn,” he said. “So when teachers don’t have an opportunity to do that, for some teachers, that might be a decision about whether to stay in the profession.”

Domenech, the superintendents association leader, said schools already feel pressure to reopen, “guidelines be damned.”

Actually, he said, the bigger threat is not the president but his base, “the parents that follow him and support him,” he said. “They go to his rallies without wearing masks. Those parents are the ones that are going to send their kids to school because they believe that this is all a hoax and that it’s safe to do it.”

He said many of these families aren’t thinking through what might happen if a teacher contracts COVID-19 in school. It would require a disruptive shutdown for everyone while workers sanitize the building.

“How many times during the course of the year are you going to do that?” he said. “And who are you going to replace that teacher with? These are the logistics of all this madness that nobody considers except the people who have the responsibility to do it.”

Noel, the Florida tennis coach, said he loves his students but must also consider his family, which includes a daughter who is a doctor and a son-in-law who is a physician’s assistant in a prison. “They risk their lives every day,” he said. “Please do not put another family member at risk by sending us to perilous unpredictable classrooms.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)