School Reopening ‘Churn’ Distracting District Leaders from Focusing on Improved Remote Education & Student Engagement, Researchers Find

School districts’ responses to the pandemic continue to be thrown off course by leaders’ assumption that things will soon return to “normal,” researchers at the Center on Reinventing Public Education conclude in their latest snapshot of reopening plans in 100 U.S. school systems.

In the absence of clear public health guidelines, district decisions about bringing students back into classrooms in person — and now, going entirely remote again as COVID-19 cases surge nationwide — are “once again raising the specter that a churn of shifting reopening plans will detract leaders’ focus from academics,” a synopsis of the analysis warns.

Since March, CRPE has been tracking school systems’ handling of the crisis, creating a database of pandemic plans and launching The Evidence Project, to identify problems and potential solutions. More than 150 researchers at 100 institutions are contributing to the effort.

School leaders must decide how to navigate a daunting series of tradeoffs, CRPE analysts note, potentially threatening their ability to increase the quality of remote instruction and begin to stanch learning losses. They must decide whether to prioritize spending on health and safety measures to bring students back in person or on ensuring students who still lack technology have devices and internet access to participate in remote classes.

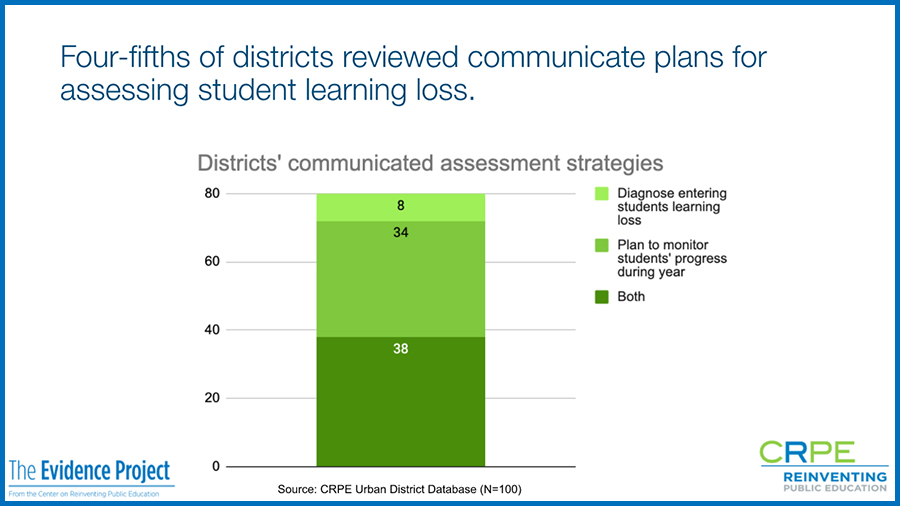

Similarly, while many districts are assessing students to identify gaps that opened or widened during school shutdowns, it’s not clear whether the data being gathered will allow educators to make decisions about where to concentrate resources or to address the academic backslide.

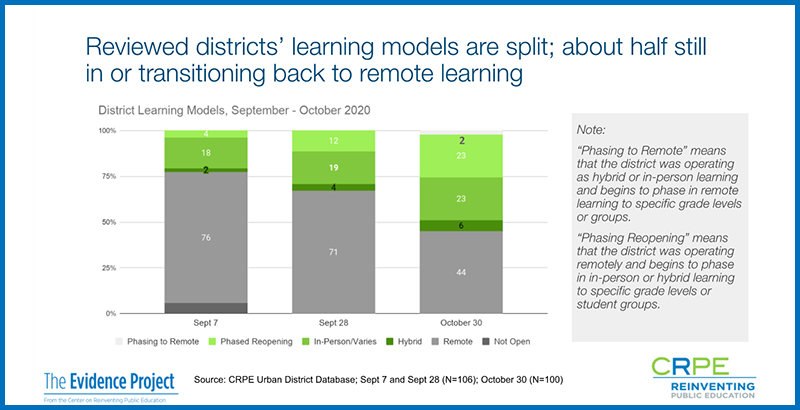

In its November update, CRPE noted that the number of districts offering at least some level of in-person instruction had more than doubled since September, to 52. Forty-four remained fully remote, as opposed to 76 at the start of the school year.

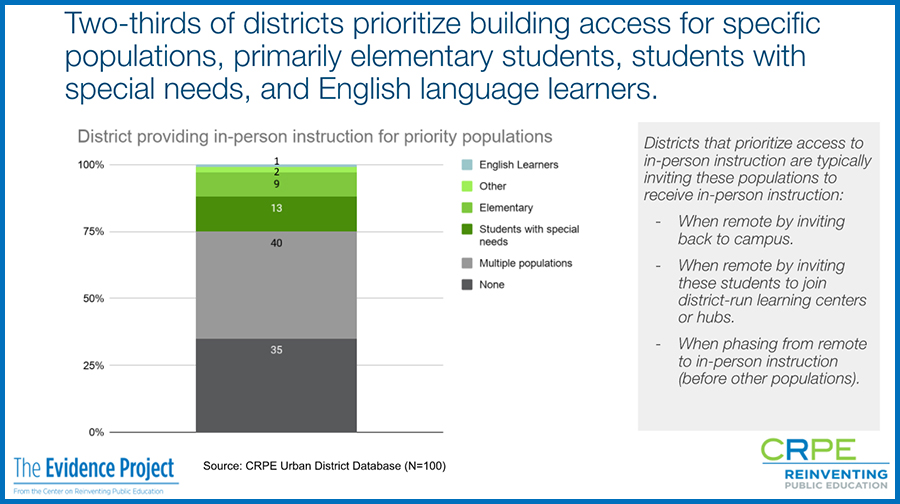

Of those that have welcomed students back to physical classrooms, two-thirds prioritize access for special populations, including English learners, elementary pupils and students with disabilities.

A surge in COVID infections, however, has forced a number of urban districts, including Atlanta, Boston and Denver, to delay reopening. And even before case counts began rising, a sizable number of families preferred to keep their children in remote settings, begging questions about student disengagement and the quality of distance learning.

Four-fifths of the districts in CRPE’s sample have plans for assessing student learning, with eight administering diagnostic exams at the start of the year, 34 planning to monitor student progress and the rest planning to do both. The majority, however, do not say what assessments they will use, with just 16 employing a universal, standardized screening test such as NWEA’s MAP or the i-Ready.

“Districts’ choice of assessment tools can be critical,” the analysts say. ”A universal test allows leaders to assess student learning needs across schools, and it helps districts strategically allocate resources (like tutors or extended learning time) to schools where students need the most help. Relying on assessments tied to specific curricula instead of common standards, or created by individual educators, won’t help leaders make these crucial system-level decisions.”

Some districts have linked their assessments to intervention plans, though a third don’t say how they will address any problems flagged. Those that do describe plans for helping students catch up say they will use small-group instruction or a combination of strategies.

Just a fifth of districts specify how they are identifying and reaching out to chronically absent students, with phone calls home the most common strategy. A handful are prioritizing disengaged students for in-person classes and making home visits.

“Atlanta Public Schools consistently monitors student logins and attendance, and developed a plan to escalate communication with families of disengaged students,” the researchers note. “When students are not logged on or do not remain online throughout the school day, staff make daily phone calls directly to their parents or guardians. When students have not logged in over a three- to four-day period of time, or staff are unable to contact their family, staff visit them at home.”

In a separate analysis of a nationally representative sample made up of 477 school districts, CRPE noted that the proportion of schools open for in-person learning is largely unchanged from August, but only because the number moving to invite students back is virtually the same as the number shifting to fully remote learning.

A lack of leadership, the earlier report notes, has left schools in crisis mode, scrambling to deal with public health questions amid fluctuating COVID-19 case counts instead of improving engagement and academics. President-elect Joe Biden has already signaled an awareness of the need for a coordinated response, but can go further, the researchers say.

“Spring was lost when the pandemic caught everyone by surprise,” they conclude. “Summer was wasted as many of the nation’s largest school systems were forced to abandon or delay plans for in-person learning. Now, schools are nearing the end of their first semester, still grappling with public health challenges and unable to focus fully on student learning.

“Providing clearer public health guidance is a vital first step, but the new administration’s efforts should not end there. It should also push states to take a more assertive role, setting clear expectations for student learning and providing more support to districts’ efforts to engage students and address learning loss.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)