School Leader’s View: NYC’s New Chancellor Admitted We’re Teaching Reading All Wrong. Now Is the Time to Get It Right

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Last week, New York City’s incoming schools chancellor made a stunning acknowledgment: The nation’s largest school district has been teaching reading the wrong way for 25 years.

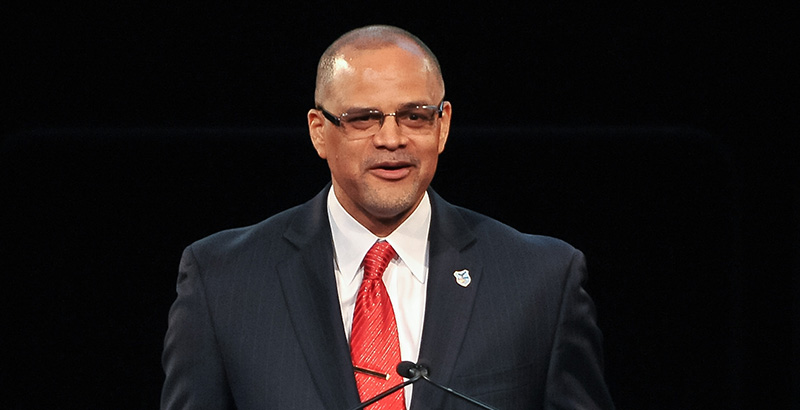

David Banks said clearly that balanced literacy — an approach used around the country — doesn’t work, particularly for low-income students. Instead, phonics-based instruction is what students need.

This acknowledgement can be game-changing not only for New York City’s school children, but in schools across the country that ought to be examining whether they, too, have been teaching reading the wrong way.

The science of how kids learn to read is clear and direct. Reading is a code, and to crack the code, you teach the code. There are 26 letters, some having more than one sound. When some of those letters combine, there are even more new sounds. Learning to read means gaining the ability to hold these different sounds and sound combinations in your brain and then honing those skills to access them at an increasingly fast rate. A strong and effective phonics program unlocks comprehension, as fluent, accurate readers free up their mental space to grapple with increasingly complex words — and complex themes.

Under balanced literacy, schools mix phonics with a “whole language” approach. Rather than teaching letter sounds and combinations, it sprinkles phonics into an environment filled with books under the theory that this will organically produce new readers. The problem is that this ignores decades of research into the science behind how kids’ brains actually learn how to read.

The effects have been devastating, particularly for children of color and from low-income backgrounds. In New York City, for example, under balanced literacy, fewer than 30 percent of fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2019, according to federal data.

Allowing poor reading skills to go unaddressed is the equivalent of the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. The reading rich will continue to grow, because with every new book they read, they build new vocabulary and knowledge, which allows them to access even more complex text. But for the reading poor, a struggle to read will only deepen the deficit over time unless the child’s teachers intervene quickly at the point of error.

The good news here is that the incoming chancellor might now light a path for millions of children — not just in New York City, but in the rest of the country as well, to ensure that educators no longer ignore the science of reading.

To be clear, teaching phonics isn’t about rote memorization of sounds. It takes a lot of cognitive work to decode a word, and strong phonics instruction puts that work on students. The teacher’s role is to prompt students with the right questions that lead them to learn sounds and sounds strung together. When students make a mistake, rather than correct it or give the answer, the teacher should guide them to correct their own errors. This leads to deeper, longer-lasting learning.

Most schools say they “do phonics.” But “doing phonics” is quite different from doing it well. True phonics programs address the brain science around reading. At a time of teacher shortages and extreme stress on educators, delivering effective phonics instruction requires support and resources. Teachers have never been more critical, and it’s never been more important to invest in supporting teachers.

At Uncommon Schools, our educators are getting up to 70 hours of literacy training this year, with a focus on the science of reading. Teachers must understand the human brain and the different areas that come into play as a child learns how to read — the occipito-temporal region, which recognizes the letter shapes; the parieto-temporal region, which turns those letters into sounds; the frontal lobe, which controls speech; and the temporal lobe, which controls language comprehension. This is not something that many top universities and colleges teach in their education schools, or even require for education majors.

For most adults, reading is so automatic that it’s easy to forget all the different components that go into interpreting words on a page. But it’s essential to break them down so that teachers can understand the process their young students are experiencing — or struggling with — right before their eyes.

Students also need to be given the opportunity to access rich, complex texts that are culturally responsive and provide them windows into different cultures and mirrors that reflect and empower their own identities. Kids should be exposed to a very broad range of identities — seeing themselves, their families and people they know in the materials they read.

These three big commitments — basing reading instruction on the science, arming teachers with support and training, and providing students with complex and culturally responsive texts — are the foundation for developing strong readers.

Schools that can provide these three levers will produce readers who will have a vastly different world ahead of them than those whose schools don’t. Banks gets this. Now, hopefully, hundreds of thousands of New York City school children will, too.

Juliana Worrell is chief schools officer K-8 for Uncommon Schools, a network of 57 public schools serving 21,000 students in three Northeast states.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)