School Director’s Belief that All Students Can Learn Is Long-Held and Personal

How a switch in curriculum led more students in this Tennessee school to learn to read than ever before

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This is the second in a series of three articles from a Knowledge Matters Campaign tour of school districts in Tennessee spotlighting the impact of the state’s investments in training all teachers in the science of reading. At Milan Special School District, leaders and teachers alike proclaim the powerful impact of their “sounds first” literacy curriculum and high-quality foundational skills program. In this piece, MSSD Director of Schools Jonathan Criswell shares how his commitment to the belief that “all students can learn” became even more personal with the birth of his son Trent. Follow the rest of our series and previous curriculum case studies here.

The idea that “all students can learn” has driven me as an educator for more than 20 years. Beginning in my classroom as a teacher, extending to leading a school building as a principal, and now in my daily experience as a school superintendent guiding a district, making sure that belief is played out on a daily basis has often been challenging, and yet it has always been rewarding.

This belief planted its roots in me during an experience with one of my earliest students. I met John as a first-year teacher. He walked into my middle school computer classroom with his fiery red hair and a personality and intelligence that were both tremendously above average. John could fix anything. His favorite was motorcycles, but that also included my often-broken classroom computers. However, John struggled to read and that bothered me. At the time, I didn’t know why such intelligent students were not able to perform the most important skill in education. It was then that literacy became the foundation of my belief that “all students can learn.”

As a principal, I learned from several passionate educators about phonemes, blends and dyslexia. Determined to create a school structure where “all students can learn,” I invested school resources into Orton-Gillingham-based interventions where students, including those students with strong dyslexic tendencies, experienced great success. Watching parents cry as they heard their struggling learners read with fluency was all the reward I needed to overcome the struggle of “doing school differently.” I clearly saw that our team was making a difference.

On October 18, 2012, the driving belief that “all students can learn” manifested itself into a personal mission for me and my family. Our son Trent was born completely perfect that day, including with one extra chromosome. His life with Down syndrome looks similar to the journey of those struggling students I had passionately served throughout the course of my career. Only this time, my experience would extend beyond the school day into my home.

I asked the same questions I had been challenging myself and my colleagues with for years: “What does the student need?” and “How do we provide it?” Grounded in my belief that literacy is the foundation of learning, I was determined for Trent to be an independent reader.

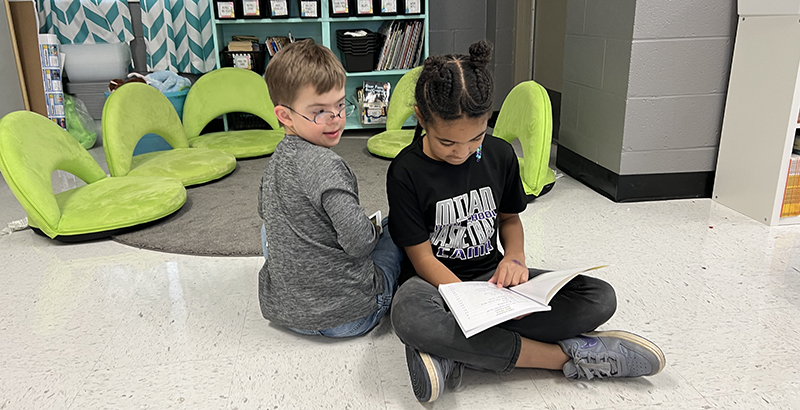

Trent is now a second-grader, living his life and having a ball. He is not yet an independent reader, but he has the foundational literacy skills to access the knowledge-based curriculum we use — and thus the path paved to get him there. The world is opening to him and his future is bright. There’s a vivid sense of accomplishment in his eyes when he knows he’s sounded out a new word on his own. I want that for all students.

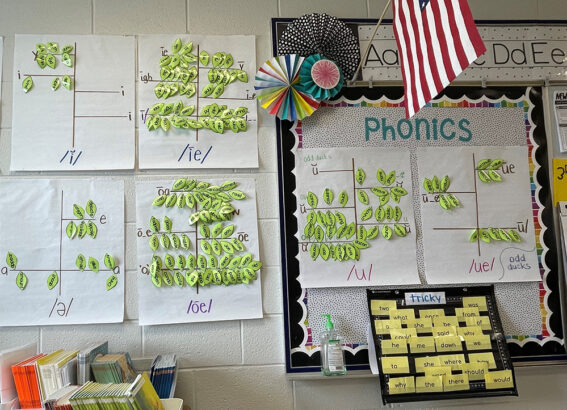

Trent’s district, Milan Special School District — which I also lead — recently made the change to a “sounds first” literacy curriculum for all students, not just those receiving intervention. In the summer, 100% of our Pre-K-4 teachers, including special education teachers, participated in a robust two-week training program on the science of reading and sounds-first instruction provided by the Tennessee State Department of Education. As a result of this training, and the adoption of a powerful high-quality foundational skills program, I’m ecstatic to report that Trent is in good company, as anecdotal evidence from educators — which we expect to soon be confirmed in our data — says more of our students are learning to read than ever before.

And, they’re learning at a faster rate. Our teachers see the difference in their classrooms.

“I see a lot of growth since the beginning of the year with my kids, especially my struggling readers,” first-grade teacher Anna Eaton told the Knowledge Matters Campaign. “I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that they like the readers; it makes them feel confident. When we have free time, it is awesome because they will pull out their readers to read ahead. I don’t mind because they want to read ahead. They want to see what happens next. Seeing them sound out the words and really use the tools we have been teaching them all year, it is awesome to see it transpire.”

Teachers overwhelmingly agree that our new curriculum is the missing piece we have been looking for in reading instruction. They have also expressed their appreciation for a developed curriculum that they don’t have to bootstrap themselves, particularly a uniform one, allowing teachers to collaborate and offering all students an equal education.

“We’re teachers, not curriculum writers,” kindergarten teacher Sarah Wilson said. “I’m thankful that now I can just teach it.”

Our students’ families are seeing big differences at home and on road trips as students are even helping their siblings learn to read and sound out road signs. Jackie Hopper, the district’s supervisor of secondary teaching and learning, said her granddaughter’s progress has been astounding — the kindergartner didn’t know the full alphabet at the beginning of the school year.

“I was trying to be patient. She didn’t do pre-K because of COVID,” Hopper said. “[The other day] I asked her to spell ‘pop’ to me, and she sounded it out ‘P-O-P.’ That’s how they learn now.”

All students can learn. I believe that and I am experiencing it. To watch teachers and administrators embrace the high-quality curriculum, to hear parents recognize their child’s success, and most importantly, to see students become independent readers, is the evidence of hard working teachers using high-quality curricula.

Jonathan Criswell is the director of schools for Milan Special School District in Tennessee.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)