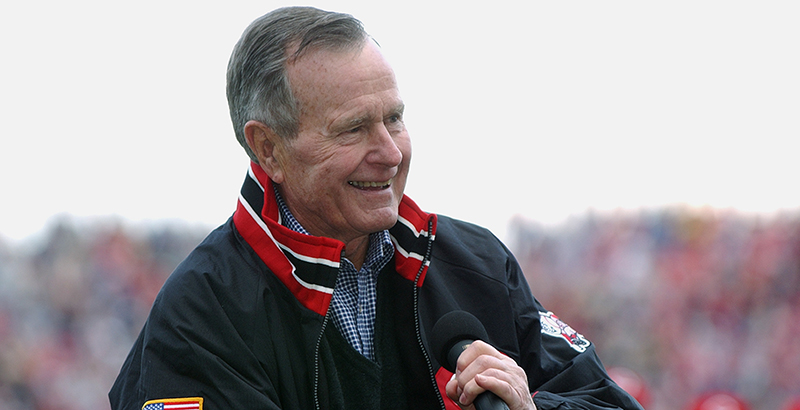

Rotherham — In Appreciation of George H.W. Bush’s Education Legacy: Bipartisanship, Equity, and Our Ongoing National Conversation About School Standards

As the nation acknowledges President George H.W. Bush’s extraordinary legacy of service from the battlefields of the Pacific to the Oval Office by way of a lifetime of service in various elected and appointed posts, we might pause to also reflect on his consequential role in education. In fact, while the ceremonies and funeral arrangements were unfolding in Washington, education types were streaming into the city for Jeb Bush’s Excel in Ed conference — more familiarly known as JebFest — a timely reminder that despite the pushback, acrimony, and evolution of education policy, we’re fundamentally still operating in an education world his father was instrumental in creating.

It seems like ancient history now, especially in today’s frenetic news cycles during which weeks feel like months, but it was not that long ago, in 1989, when Bush and then-Arkansas governor Bill Clinton called the nation’s governors together to discuss education. It was bipartisan, intergovernmental, and rare. When the National Governors Association is in Washington, its members customarily meet with the president, but rarely does the president convene them for a summit. Teddy Roosevelt did it to discuss conservation, Franklin Roosevelt for the economy, and then the third time was when George H.W. Bush assembled the governors in 1989 in Charlottesville, Virginia, to focus on education.

The summit set in motion education policymaking that still largely shapes what we do today. Because of suspicion and outright opposition on the left and right, Bush couldn’t get a national education plan through Congress, but in 1994 Clinton succeeded with a compromise measure. That legislation, the Improving America’s Schools Act, required states to set standards and periodically assess student progress against them. Perhaps as important, Clinton gave states resources for this work via the Goals 2000: Educate America Act, an idea with roots in the Charlottesville meeting. Clinton, who had visited the nation’s first charter school during the 1992 campaign, also set a course for charter schools with an ambitious goal for 3,000 of them by the time he left office.

The 1994 law was in many ways a more significant policy shift than its successor, the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act. The Improving America’s Schools Act embedded standards in federal policy — albeit without real consequences attached to them, but it was a sea change nonetheless, given the religious adherence to local control of schools in America. The 2001 law, championed by President George W. Bush, tried to address the complaints of civil rights advocates and others by requiring states to make their standards meaningful by employing more robust accountability systems and assessing students annually, something that fewer than 20 were doing at the time. A Republican, Bush was more of a champion for real accountability for educating poor and minority students than most of the interest groups in the Democratic ecosystem.

An education apparatus that is allergic to accountability not surprisingly revolted. And after the law was long overdue for overhaul and everyone was exhausted of the fight, then-President Barack Obama ultimately let states more or less do what they wanted, an approach codified in the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015. Yet despite the rollback, the baseline commitment to standards remains. And over the past decade, through Common Core and other work in various states, there has been a lot of focus on improving the quality of state standards. Meanwhile, choice, in a variety of forms but most commonly through charter schools, steadily expands as frustrated parents and courageous politicians find each other.

Today, moderate pro-reform Republicans and moderate pro-reform Democrats need each other but seem unable to connect in the hothouse of today’s politics. As both parties are pulled toward their extremes, the 1989 Charlottesville summit seems not only distant but quaint. Even the more transactional compromises of 2001 and the pro-No Child Left Behind alliance between George W. Bush and Sen. Ted Kennedy seem out of reach in today’s climate. Kennedy battled for more education funding for NCLB, but he stubbornly resisted efforts to water down the policy, at one point even taking his Democratic colleagues to task on the Senate floor. In 2012, I spoke with George W. Bush on the 10-year anniversary of the law, and he made the case that conservative opposition to NCLB was anything but conservative while continuing to work across the aisle on education when he could.

In any event, alternately delighting and infuriating Democrats seems to be a Bush family trait. Jeb and George racked up impressive state-level records on education as part of a bipartisan cadre of Southern governors doing the same, following in the footsteps of their pragmatist father, who keenly felt the cross-pressure of the political imperatives of elected office and the values he sought to uphold. His 1990 budget deal was a risky political bet that failed to pay off. The Willie Horton ad remains an open wound in a hard-fought campaign (Al Gore’s role in the episode has been blown out of all proportion in revisionist retellings).

Early in his career, when he became chairman of the Harris County Republicans, Bush put the party’s money in black-owned banks, but while running for the Senate from Texas, he campaigned against the Civil Rights Act — something he later regretted. Yet, once elected, Bush voted for a fair housing bill wildly unpopular among conservatives in his adopted state and elsewhere, just as he would later buck conservatives on education. In the wake of Bush’s death, the Rev. Jesse Jackson told The Associated Press, “[Bush] was a fundamentally fair man. He didn’t block any door. He was never a demagogue on the question of race.”

Our current president claims to be a consummate dealmaker. So far, it’s hard to see. But the deals that set the stage for the current educational era started when politicians who understood the art of the political deal, President George H.W. Bush and Gov. Bill Clinton, sat down in Charlottesville and set education policy on a path it’s still largely on today.

It’s an important part of the 41st American president’s broad legacy.

Andrew J. Rotherham is a co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education, a national nonprofit organization working to support educational innovation and improve educational outcomes for low-income students. He is a senior editor at The 74 and serves on the 74’s board of directors. In addition, among other professional work, he is a contributing editor at U.S. News & World Report, writes the blog Eduwonk.com, teaches at The University of Virginia and is a senior advisor at Whiteboard Advisors. Rotherham served as special assistant to the president for domestic policy during the Clinton administration.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)