Rotherham: Biden’s School Pandemic Relief Funding Is an Opportunity, but One With Risks. Spending Without Planning First Could Be Costly

If you suddenly came into a financial windfall, would you spend it right away? Or would you pause and plan a little bit for the long run before burning through it? Would you spread it around on lots of little things or figure out a few places that are most meaningful for you?

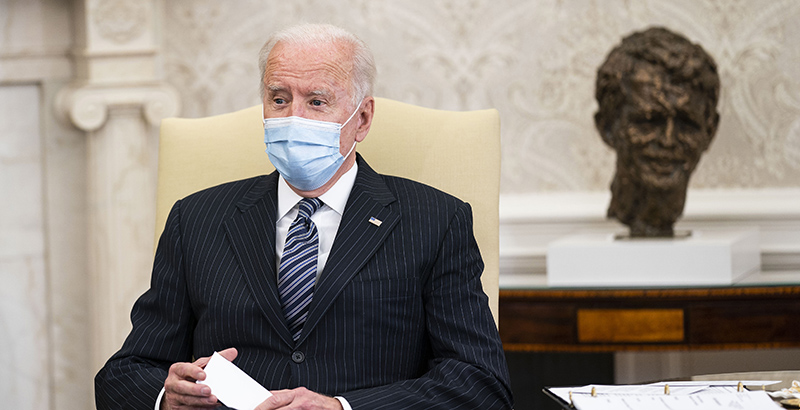

Although it’s not an inheritance or winning lottery ticket, the staggering $123 billion in federal education aid for K-12 schools in President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act is posing that basic question for state education policymakers and local school leaders.

The reflexive answer is states should spend it now, as fast as possible. After all, wasn’t the pandemic an unmitigated fiscal calamity for states and schools? It turns out, no. The impact has been less severe than anticipated. There are pockets of acute problems: For instance, state revenues for tourist-dependent Nevada and Florida are down more than 11 percent. But overall, the fiscal situation is manageable. Some states are trying to figure out what to do with surpluses, which is good news. And it’s in part because previous federal stimulus packages during 2020 kept consumers spending.

Schools also received support last year. In total, including the Biden plan, America’s K-12 schools have received an infusion of about $200 billion in federal dollars since the pandemic started last year. That’s an increase of almost 27 percent relative to total annual spending. There are additional streams of federal funding states can choose to spend on school operations. In other words, states and school districts are sitting on an unprecedented (an overused word but appropriate here) amount of money and, consequently, an unrivaled opportunity to improve school for kids. For most states, this is all happening at a time of relative fiscal stability despite the pandemic.

It’s an opportunity, but one with risks. First, rather than focus the new money on a few problems, districts may instead spread it around to accommodate all the various political and substantive demands they face. Despite its scale, this funding could be spread so thin — a little tutoring here, a little class size reduction and across-the-board raises there — that in the end, it will have little impact on student learning.

This risk is compounded by how the Biden money is sent to schools. At least 90 percent of it passes through states to local districts. That’s good news for local flexibility. Yet, as former Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen, who led his state through the last big federal relief package for schools during the Great Recession, points out, it’s also a liability. A hundred dollars spent to address a problem is often more effective than one dollar spent a hundred times, Bredesen cautioned in a recent discussion about the Rescue Plan Act.

The structure of the funding may be an overcorrection to the Obama administration’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and Race to the Top initiative. Race to the Top dollars, for instance, were conditioned on specific state actions, such as implementing teacher evaluation systems or intervening in low-performing schools. Some state leaders bristled at what they saw as federal overreach and micromanagement.

Today, mandating specific reforms would not make a lot of sense, given the different reform strategies states are pursuing, varied state experiences with the pandemic and schools, and the political climate. These dollars can instead support an array of reforms chosen by the states and districts themselves. Tutoring to offset missed learning, initiatives to diversify state teaching forces, extending learning time, class size reduction focused on the most at-risk students, strategies to increase educational choices for parents, technology and online learning, or school air and water quality improvements are just a few of the good ideas out there.

While effective reforms vary, what they have in common is effective implementation and real adherence to whatever underlying elements made those initiatives effective in the first place. In a word: planning.

A lack of planning is the second risk. States and school districts have varying deadlines for using the relief funds and can use other federal pandemic relief dollars to plan and leverage the Biden funds. Districts can operate on even longer timelines. No one needs to wait years. However, time spent now figuring out how to organize stakeholders, use various incentives states can offer and leverage this incredible windfall most effectively will increase the impact. And because any plan must be bottom-up to get local school district buy-in, these dollars might bring about some structural changes past reforms failed to achieve.

For now, though, despite some emergent planning supported and led by foundations or trade organizations, it’s hard to miss the signs of a gold rush as vendors and special-interest groups lick their chops at the prospect of millions of dollars flowing largely unchecked into school districts. The scale is incredible: Bredesen’s Tennessee won about $500 million (payable over four years) after months of planning and intense competition with other states. By comparison, Metro Nashville Public Schools alone are receiving a total of $424 million in pandemic relief funds right now.

Yes, obviously I’m the co-founder of a nonprofit organization that specializes in planning educational initiatives, so you might be thinking, “Well, of course he’ll say to plan.” But I’m also a former state official and have worked in education reform through a few boom and bust cycles. If prudence doesn’t convince you that pausing and planning makes sense, then perhaps politics will. What happens in a few years if there are few discernable impacts from all this spending? Politics is unpredictable, but hastily squandering more than $100 billion in funding could set back efforts to make school finance more equitable for low-income, Black and Hispanic students for decades. Or it could create a backlash against education spending more generally if there is no compelling story to tell in a few years. We could look back at this windfall as more of a curse than a blessing. There is a reason most cultures and faith traditions have cautionary tales about how abundance can rebound in unexpected ways.

Why chance it? Education leaders would do well to heed the common-sense advice of carpenters: Measure twice and cut once. This is a rare opportunity for real change with staggering sums of money — if education leaders pause to figure out how to make the most of it.

Andrew J. Rotherham is a co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education, a national nonprofit organization working to support educational innovation and improve educational outcomes for low-income students, and serves on The 74’s board of directors. In addition, among other professional work, he is a contributing editor at U.S. News & World Report, writes the blog Eduwonk.com, teaches at The University of Virginia and is a senior advisor at Whiteboard Advisors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)