Role of Equity in Reading Tests Divides Board Overseeing ‘Nation’s Report Card’

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

When students read, do their personal and cultural backgrounds determine how they understand the text, or are the skills and knowledge they pick up in the classroom more important?

That’s a question currently dividing the government body that oversees what is known as The Nation’s Report Card.

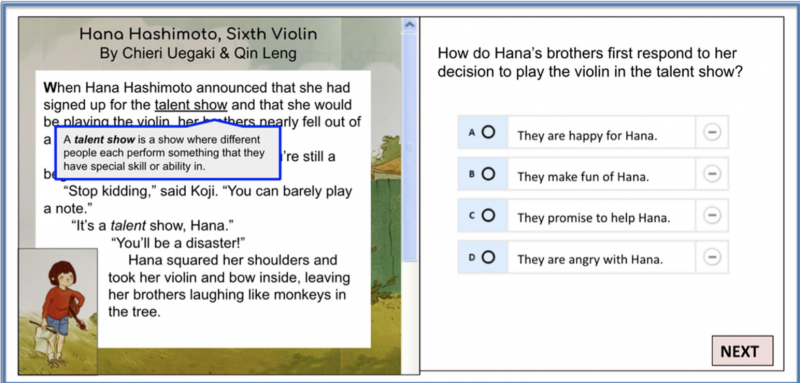

The dispute centers around the role of equity in a lengthy document that could determine how the federal government designs future reading tests. The authors filled it with references to “pop-ups” or short videos defining words or terms some students might not recognize, such as a talent show.

But others on the board view the emphasis on removing bias and increasing fairness as divisive in the current political climate.

The board won’t vote until August, and the updated “framework” wouldn’t affect tests until 2026. But the disagreement over the testing program, often referred to as the “gold standard” of student assessments, comes amid a nationwide push to improve education for children of color. And it reflects a longstanding tension between those wanting to make the program relevant to contemporary issues and others primarily concerned with accurately measuring how students’ reading skills have changed over time.

Such conflicts aren’t new for the National Assessment Governing Board, which Congress established in 1988 as an independent and nonpartisan overseer of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. But remote meetings necessitated by the pandemic have made those differences harder to resolve than they would have been in person, said Andrew Ho, an assessment expert at Harvard University and former board member.

He predicted “fewer unanimous votes ahead” when he left last year.

“NAEP has always been above the fray, relative to everything else,” he said in an interview, adding that if issues before the board are becoming more controversial, that’s because “everything else is, too.”

A panel of 18 curriculum experts completed a draft of the framework on April 21. Board members in favor of that version have directed criticism at colleague Russ Whitehurst, who this month offered his own line-by-line edit, cutting most references to “sociocultural” factors and words such as equity, bias and fairness. He emphasized other areas that influence reading comprehension, including curriculum and instruction, teacher quality and students’ background knowledge.

During a May 7 virtual meeting, board member Christine Cunningham, a professor at Pennsylvania State University, said Whitehurst’s version is “decidedly not a document that I can agree with.” The terms he removed, she added, “are the words that experts use. I don’t think they should be omitted or treated as objectionable.”

‘Measuring what’s changing’

The governing board decided in 2019 to update the document, which hasn’t changed since 2004, to reflect current research on how students make sense of what they’re reading and that students now read a variety of both digital and traditional materials.

The challenge is “trying to measure what is relevant while also measuring what’s changing,” Ho said. “The way we read now is not the way we read 20 years ago.”

The panel writing the document drew on the findings of a 2018 National Academies report, “How People Learn II,” which concluded that learning depends not only on the knowledge students gain in the classroom but on the cultural experiences they bring to the process.

The experts’ draft focused heavily on how the pop-ups and other “universal design elements” in a computer-based test would make the reading passages more accessible for all students. The elements are essentially hints that might explain a word or phrase not all students would recognize.

Such features are intended to pique students’ interest or prepare them for what they are about to read. They could even motivate students to try harder on a test that doesn’t affect their grade, said Mark Miller, a board member and a math teacher in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

The elements are not meant to affect the material students are actually being tested on or give one group of students an advantage over another, according to an explanation from the board’s “technical advisory committee.”

That assumption is open to debate. During a public comment period in 2020, the board held eight webinars and collected over 2,600 comments. Some groups supported the emphasis on social and cultural factors, but others were concerned adding too many elements “might yield a test that all students would be able to pass,” according to a summary of the changes.

In response to the public and other board members, the panel toned down references to the role of culture and background in the document, and opted not to add more of the elements in the test.

Board member Julia Rafal-Baer, chief operating officer of Chiefs for Change, said she’s concerned that if critics of earlier drafts don’t understand how the panel addressed their concerns, “We are going to completely lose both sides of the aisle.”

‘An undesirable position’

But those changes didn’t satisfy Whitehurst, past research director at the U.S. Department of Education during the second Bush administration and a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. For example, he deleted a sentence that reads, “Research has shown that a student’s background, language, and experience is important in how they interpret assessments.”

He wrote that he doesn’t want the board members or the testing program to be forced to accept “a particular point of view of what is most important in learning to read.”

At another meeting last Thursday, he said he didn’t think the edits he wants “should be onerous or upsetting to people unless they have an agenda that is not on the surface.” He added that while the panel’s draft included several references to fairness, it’s “missing explanation on what we find unfair that we hope to correct.”

Board member Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University, shares Whitehurst’s concerns. He said the board has gotten itself in “an undesirable position” and has conflated the assessment of reading with the goal of improving reading.

“The latter is not in our charge,” he said.

Work-related communication

One additional layer to the governing board’s recent discussions is an internal letter from former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour, board chair, to other members. The letter, according to two conservative observers who have read it, said members can no longer communicate with each other or outsiders regarding official matters unless they share those messages with board staff. The chat function in Zoom has been disabled to further prevent side conversations.

Chester Finn Jr., president emeritus of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, and Rick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, suggested the letter was meant to stifle criticism of the reading framework document.

But Stephaan Harris, a spokesman for the board, said the letter complies with guidelines for work-related communications that now apply to all special government agencies and employees.

“It had nothing to do with the framework or any specific issue, action or policy,” Harris said, adding that Finn’s and Hess’s “pieces incorrectly conflated the two, so that caused some unfortunate confusion.”

Finn, a former chair of the governing board, also linked the controversy to the larger “culture wars,” and wrote that an updated view of reading would extend beyond the assessments and “gradually percolate through the entirety of K–12 education in America.”

“In the ‘real world’ of reading outside school, there are no supports,” he said in an email. “Either you possess the [vocabulary] and knowledge that you need to understand what you’re reading or you don’t. And if you don’t, you likely won’t understand stuff.”

But Patricia Anders, a University of Arizona reading professor, said it’s important to focus on children’s strengths. She was among those who wrote letters last week to the governing board rejecting Whitehurst’s edits.

“Everyone knows that culture and language influences learning to read,” she said. “Teachers don’t ‘fix’ language and culture. They work with what the learner brings to the learning-to-read context.”

Ho, at Harvard, said he thinks the board members will eventually work out their differences because NAEP is such an important “barometer” of student progress.

“At the end of the day, everyone needs NAEP,” he said. “No matter what happens with this framework, I’m confident that people on both sides of this issue will come to support what comes out of it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)