Rise of Fake News Gives New Urgency to Media Literacy Education in America’s Schools

This article first appeared on the blog of the Education Writers Association

The advent of fake news was the worst-best thing to happen to media literacy in schools.

That’s according to Sherri Hope Culver, director of the Center for Media and Information Literacy at Temple University.

In years past, it was tough convincing legislators and reporters that how children are taught to analyze and evaluate media is important, Culver said during a recent Education Writers Association seminar in New Orleans. They’d ask what made the issue timely.

“And then we had an election,” she said, referring to the 2016 presidential race. “And it’s not about who got elected. It’s about how information was conveyed. How did people make decisions? That has raised the conversation about media literacy. If fake news is the way in, I’m all for it.”

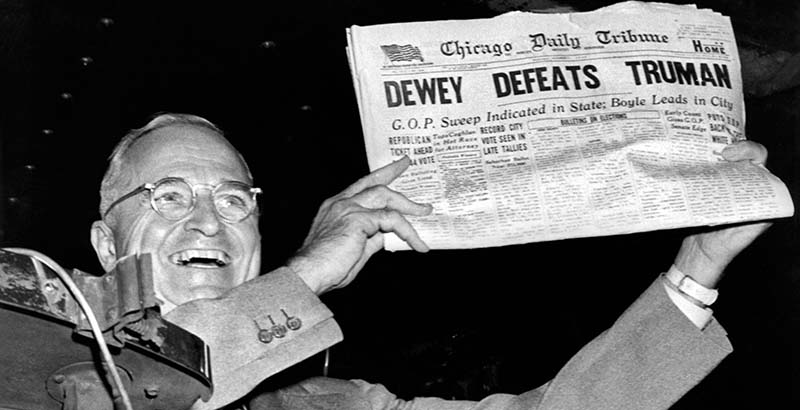

The 2016 election season saw fake news — false or intentionally misleading information disguised as authentic news — produced and disseminated at a historic scale. A sophisticated disinformation campaign by Russia, the ease with which stories can be shared across social media, and a presidential candidate with a habit of spreading baseless claims proved a powerful combination.

A recent analysis found that the most popular fake election news stories were shared more times on social media than the most popular stories in the mainstream news media.

A ‘Vaccine’ for #FakeNews?

Some, like Culver, are touting media literacy education as a solution to fake news. She was one of three experts at EWA’s seminar in New Orleans on educating for character and citizenship to discuss schools’ responsibilities in teaching students how to discern between false and credible sources of information.

Speaker Damaso Reyes, director of community partnerships and engagement at the News Literacy Project, agreed: “There is a cure — or, perhaps better put, there’s a vaccine — to fake news. That vaccine actually is news literacy education.”

For a generation of digital natives, understanding what’s real still proves challenging.

Nearly half of children ages 10 to 18 said they can distinguish between a fake news story and a real one, according to the results of a 2017 Common Sense Media survey of 853 kids nationwide. At the same time, 31 percent said they had shared a story on social media in the past six months that they later discovered wasn’t true.

About half of teens said that following the news is important to them, the survey found. Students said social media was their major source for news, with YouTube and Facebook reported as the two most popular platforms.

Finding Space in a Crowded Curriculum

When Jana Chao, a fifth-grade teacher in Clinton, Mississippi, teaches media literacy to her students, she tells them to identify whether there’s an agenda behind a story and to think about the goals of the organization that produced the story. Chao, who spoke at the EWA event, said she also helps students consider what points of view might be missing from the message.

One challenge many educators face, said Chao, is finding time for media literacy. “You need to understand the pull that is taken from test scores and accountability. Where am I going to fit media literacy into the classroom?”

Reyes said it can be taught across the curriculum. “Media literacy actually fits in social studies, history, ELA, computer science. You can integrate that because the heart of what we’re doing is critical thinking.”

Culver echoed the point about critical thinking.

“It’s not a partisan issue. It’s not a teacher’s view about what should be right or wrong,” she said. “It’s helping you to reflect on how do you make decisions, how do you gain information in your life, so that you can do it in a way that works for you.”

Laws to promote media literacy education were recently enacted in several states, including Washington, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, as the Associated Press reported in December.

For example, the new measure in Washington requires the state superintendent to make media literacy resources available to educators and conduct a survey about how these skills are being taught. The Connecticut law, also adopted last year, created a council to come up with recommendations for teaching media literacy skills.

Teaching the Standards of Journalism

In educating students about media literacy, it’s also important to help them understand the difference between fake news and misinformation, such as a mistake reported in a news story, said Reyes.

“The landscape for young people is completely different than it was for us,” he said. “But we’re not, many of us … adapting fast enough in the world of education to say, ‘Hey, we actually need to teach young people what news looks like, why it’s important, what the standards of quality journalism are.’”

Panelists disagreed over whether students should be coached to consult multiple sources to find out if a story is real.

“We do ourselves, not just students, a disservice when we say we need multiple sources,” Culver said. “That is unrealistic.”

She argued that people don’t have time to search for multiple news reports to corroborate every story. But Reyes disagreed, saying that checking out multiple sources for emotionally charged stories should be an aspirational goal, even if not achievable every time.

“That’s something we need to inculcate into our young people, to say, ‘Listen, this is so important not to spread misinformation that you need to take the extra 30 seconds or minute or even, God forbid, two minutes in order to find out whether or not something is right,’ ” Reyes said.

It’s difficult to know how many schools teach some sort of media literacy to their students, Culver said, but she hopes teacher training programs at universities will support this kind of education.

The panel’s moderator, USA Today education writer Greg Toppo, asked whether teaching media literacy could prove problematic if parents question whether a teacher is coming at these lessons with a political agenda.

Chao said she’s earned a level of trust among the district and parents, but more important, she’s heard that the lessons around analyzing news are being passed from her students to their parents, who are also unaware of some of the markers of genuine journalism.

“You’ve got the blue check mark?” Toppo joked. “I’ve got the blue check mark,” Chao said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)