Richmond: Why School Districts Are Walking Away From Authorizing New Charter Schools — and Why That’s Both a Bad and a Good Thing

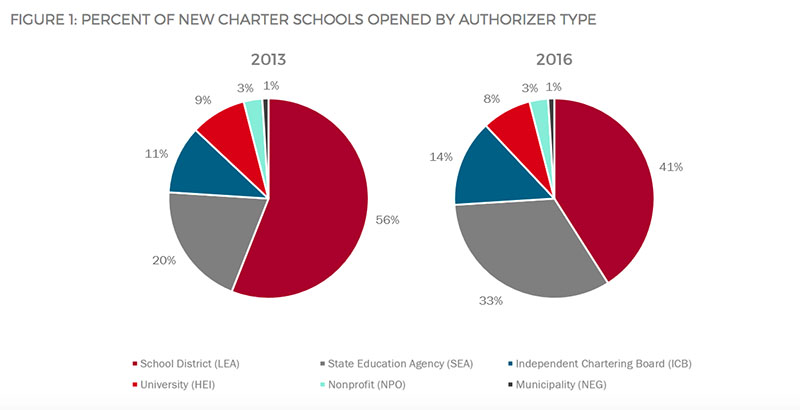

In recent years, more school districts have walked away from the opportunity to authorize new charter schools. New research from the National Association of Charter School Authorizers has found a shift in the national charter school landscape: For the first time, most new charter schools are opening under authorizers other than local school districts, with state education agencies and independent chartering boards leading the way.

In 2016, school district authorizers opened 222 fewer schools than they did in 2013. While fewer new schools opened overall during this period, the drop among school districts is striking: It’s nearly 2.5 times as large as the decrease in new charter school openings under all other types of authorizers combined.

Many districts did not slow down their authorizing activity; they simply stopped. Nearly two-thirds of districts with charter schools did not authorize a single new charter school in the past four years. Conversely, 70 percent of state education agencies and independent chartering boards authorized a school in at least three of the four years examined.

This trend is a bad thing. Yet it is also a good thing.

It is bad because millions of children in the United States lack access to a good school that will prepare them for success in life. Rigorous research has found that quality charter schools are providing better education opportunities to students, especially students from disadvantaged backgrounds. No other public education activity of the past quarter-century has been as effective for disadvantaged children as charter schools. We need to be doing more to make these schools available, not less.

So when we see local school districts — a group of authorizers that at one point was helping 350 new charter schools open every year — walk away, we know they are shunning the opportunity to provide a better education and a better future for young people who need it.

This is especially troubling because school districts make up 90 percent of the authorizers around the country. In fact, in six states — Alaska, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Virginia, and Wyoming — districts are the only entities that can authorize charters. Giving more students access to great schools requires districts to embrace, not flee, the opportunities and responsibilities that come with authorizing charter schools.

But the trend is also a good thing.

Earlier this year, our research found that the authorizers with the strongest school portfolios have an institutional commitment to charter school authorizing and see it as their mission to provide more quality options to kids. Authorizing is visible and championed within their institutional framework, not buried in layers of bureaucracy. Their day-to-day authorizing staff has meaningful influence over decision making.

These qualities are more likely to be found in authorizers like state education agencies and independent chartering boards than within school districts. It is not impossible for districts to be good authorizers — and they exist — it simply is not their core mission.

We know that districts, by far, use fewer nationally recognized authorizing best practices than any other type of charter school authorizer. In some places, districts are openly hostile to charter schools and look for any reason to decline applications.

When viewed through this lens, the shift from district authorizing to nondistrict authorizing could be a net positive, as it will likely lead to better authorizing and better charter schools. That’s why public education advocates and policymakers should work to ensure that every city and state has a nondistrict authorizer.

Experience shows that independent, statewide charter boards hold the most promise, as a singular focus on authorizing can build substantial expertise and strong practices that lead to better outcomes for children. In some places, a state education agency may be the better route; in other places, it may be universities.

There is much to learn about what is driving this trend within school districts, and whether it is possible to reverse it — or whether we should even try. Are districts receiving fewer applications, or are they denying them at higher rates? Is this all just a result of increased political opposition and competition for scarce resources?

But given that all types of authorizers are opening fewer schools, we need more great authorizers that are willing to step up, identify obstacles to growth, and work to solve them. In places like Colorado, New York, Washington, D.C., South Carolina, and Massachusetts, we see authorizers that are looking for areas of need in their communities, recruiting new operators, and creating transparent and accessible application processes. They’re working with education leaders in their cities and states to create an ecosystem that fosters innovation and policy conditions that support quality growth.

Too many U.S. children lack access to a good school. One powerful way to provide more children with a better future is through better authorizing and more high-quality charter schools. Let’s keep working.

Greg Richmond is president and CEO of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)