Analysis: New Report Shows Charters Gaining Ground in Enrollment and Services for Students With Disabilities but Still Lagging Behind Districts in Discipline and Representation

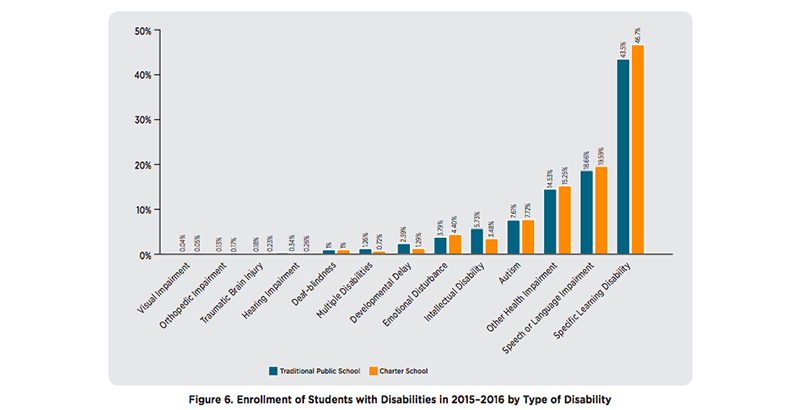

This week, my organization, the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, released its third analysis of the Civil Rights Data Collection in five years. We found that while charter schools are enrolling more students with disabilities than in the past and providing more inclusive learning environments, the sector continues to suspend those students at higher rates than traditional public schools and continues to enroll proportionally fewer students with disabilities than traditional public schools.

Numerous factors influence the ability of all public schools to serve students with disabilities; our analysis finds that while charter schools are making progress, they can do better. More parents of students with disabilities than ever are choosing charter schools, which is a positive sign, and we believe charters can drive effective change so that all schools are able to provide families with the quality education, services and supports they deserve and need.

Take Collegiate Academies in New Orleans, for example. Collegiate started as a single school, Abramson Sci Academy, that bore many of the hallmarks of a traditional no-excuses charter school: a culture that stressed college-going, an intense focus on rapidly raising test scores and strict discipline that drew student protests. The school experienced overall success. However, founder Ben Marcovitz grew concerned that not all students were having the same experience; he explicitly wanted to serve more children with disabilities, and serve them well.

Consequently, as Abramson grew into a network of charter schools, first in New Orleans and now in Baton Rouge, Marcovitz made his most complex learners a priority. The network adopted restorative justice practices and began overhauling its model to better serve students with diverse needs.

Another development added fuel to these efforts: In 2012, Marcovitz and his wife had their first child, who was born with a brain injury. They realized she might never find a public school in their city capable of meeting her needs.

Since then, the Louisiana charter network has continued to evolve. Its schools have added intervention classes for students who struggle in reading and math, and created a specialized curriculum, called the Journey Program, for students with behavioral challenges. It’s also created a new postsecondary program, Opportunities Academy, for students with more profound disabilities.

Collegiate Academies emphasizes some of the principles the Center on Reinventing Public Education and the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools identified in an October study of charter schools with strong commitments to students with disabilities. Following visits to 30 charters around the country, where researchers observed classrooms and interviewed parents, teachers and administrators, we concluded that in the most promising schools, three principles — strong, trusting relationships, a problem-solving orientation and blurred lines between special and general education — worked in concert. A critical first step is to prioritize students with disabilities and the relationships with their families in resource allocation, hiring practices and support structures.

Collegiate does just that. Its leaders have a clear vision of what kids need and are constantly looking for new ways to drive toward that vision. They aren’t committed to a set model or “secret sauce.” They’re committed to solving problems and doing what’s best for their students.

This kind of ethos starts at the top. Assertive leaders are key to ensuring schools make students with disabilities a priority. At Collegiate, this starts with Marcovitz and his personal concern for these children, and he’s hired a team of people who share that commitment.

During one field visit for our study, we asked a school leader at a Collegiate campus, who was responsible for students with disabilities, about this commitment. He answered: “Our academic goals are collective goals.”

I’ve heard this sentiment from other school leaders. But it’s not always clear they mean it when they say serving students with disabilities is everyone’s responsibility.

I suspect one reason for the low retention rate among special education teachers is that they get shunted off to the side and feel their work isn’t at the core of what their schools do. So they get frustrated, burn out and quit.

These teachers and school leaders say things about students with disabilities like, “We can’t serve those kids.” And they’d say it in a definitive way, like they were saying the sky is blue.

I understand some of their concerns. They worry that seeking to enroll more students with disabilities might cause performance scores to drop. They worry that their teachers will have to spend extra time and attention supporting students with disabilities, and that they may have to hire dedicated staff to support them.

Educators at Collegiate didn’t talk like that. And Collegiate was just one organization we visited during our study where we saw leaders prioritize students with disabilities. Our researchers met school leaders who started out as special education teachers, administrators who had family members with disabilities and one school leader who herself had an Individualized Education Program growing up.

We need more public schools — charter and district — to recognize that supporting students is not a zero-sum game. We need leaders at every school to feel as passionately for students with disabilities as those who have personal experiences. We need school leaders to make supporting every student part of their natural thought process.

When school leaders set the tone by declaring that they feel responsible for every student’s success, they reinforce practices that help all students.

Every student benefits when general education teachers receive training in how to differentiate instruction, all teachers have time and space to collaborate and solve problems, and everyone in the school is constantly looking for new ways to support students — including children with disabilities, who are affected by trauma, have behavioral challenges and are behind grade level.

They understand that all kids come to school with different needs. Good instruction for students with disabilities is good for all kids.

But right now, we are leaving the question of whether a school prioritizes students with disabilities to chance. The parents of 6.7 million students with disabilities must hope that they find a school where the people in charge have chosen to make children like theirs a priority.

We must focus on instilling the mindset in all teachers and leaders in public schools, design accountability systems that reward schools where students with disabilities make academic progress and build funding systems that give them the resources to support those students.

If we can build systems that ensure every school prioritizes students with disabilities, all students will benefit.

Lauren Morando Rhim is executive director and co-founder of the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools. A researcher and advocate, she has spent 25 years striving to identify strategies to create and sustain high-quality public schools for all students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)