Reville: Beyond the Coronavirus Shutdown, an Opportunity for a Whole-Child Paradigm Shift

Long ago, critics of school reform, like Richard Rothstein of The New York Times and the author of Class and Schools, cautioned idealistic education reformers (of whom I was one) that schools were only one part of realizing Horace Mann’s dream of an equal-opportunity society. Schools by themselves, he argued, could not, on average or at scale, equip impoverished children to achieve the levels of career and economic success enjoyed by the privileged classes. This, like the Coleman report many years before, constituted a direct challenge to the myth that schools, occupying a mere 20 percent of a child’s waking hours between kindergarten and grade 12, could function as the great equalizer in a society characterized by profound inequality in income, wealth and social capital.

Nonetheless, reformers persisted for many reasons. After all, U.S. taxpayers spend a small fortune on schooling and there is no doubt that schools can be improved and ought to be in a cycle of continuous improvement. And, as Coleman and others acknowledged, schools do matter — and there are good schools and bad schools, even when controlling for income. Nonetheless, it is still the case that the commonsense school reforms of the past quarter-century were necessary but not even close to sufficient for the task of leaving no child behind. The evidence is in and clear: After 25 to 30 years of school reform, we still have an iron-law correlation between socioeconomic status and educational achievement and attainment.

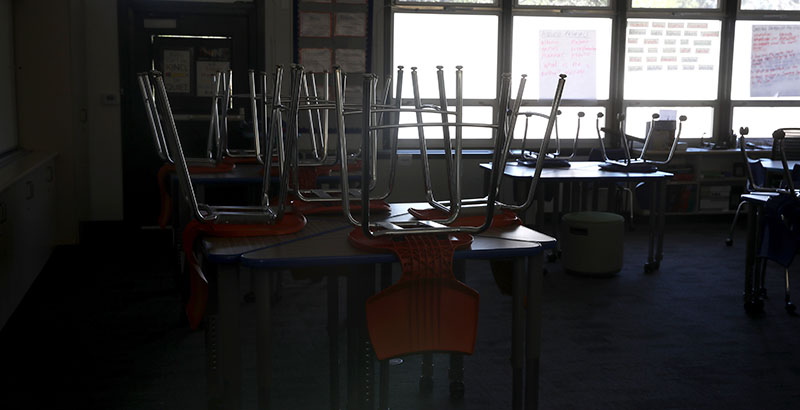

The coronavirus crisis and the accompanying school closures have revealed to the general public the profound inequities in the lives of children — inequities that have always been there and have always significantly impeded school success but are seldom acknowledged and sometimes not even perceived. Now these inequities are on the front page. Since schools are closed, pundits are paying attention to inadequate health care, food deserts, homelessness and a lack of access to different online learning platforms, apps and even the internet itself. It’s as though a big wave has pulled back the sea revealing the ocean floor and all its disturbing realities that had heretofore been hidden beneath the surface of the water. Before that wave comes crashing back down, concealing reality once again, we should take advantage of the current sense of urgency to do something.

Educators must take the lead for a change instead of having reform done to us. This refrain is as commonly uttered as it is infrequently acted upon, and we can ill afford such passivity in a time like this. Such leadership would entail articulating both the problem and a vision for how to proceed in solving it. The problem is roughly this: Our education system is not, as currently structured, capable of achieving the appropriate and urgent goals policymakers have set for the sector, goals that expect schools to educate all students to a level at which they can be successful participants in both our democracy and the high-skill 21st century economy. A vision for how to proceed: Establish systems of child development and education that meet children where they are in early childhood, and provide them with what they need, inside and outside of school, in order to be successful. Think: The kind of cradle-to-career pipeline constructed by affluent parents who provide wraparound services for their children from the prenatal period through adulthood. That’s what successful systems look like, a cradle-to-career pipeline insulated by systems of opportunity and support. They can and should be constructed at the local level, owing to the centrality of local control in American education. This can be done under the purview of children’s cabinets, with local, state and federal financing. Schools should be at the center of this work — curators and coordinators — but this is a civic responsibility for the entire community.

Right now, we see many school leaders struggling to reach out to their students and families to reconnect and establish contingency systems to provide the best possible learning under the circumstances. That’s commendable. However, if we’re just going to see this time as a holding pattern prior to restoring the status quo in all its inadequacy, then we will have failed.

With billions of stimulus dollars soon to arrive to support schools, education leaders should be at the forefront in advocating for a paradigm shift to a new holistic system of child development and education that has a fighting chance of achieving goals like “every student succeeds.” Rather than have expectations for this money blindly imposed on us, we should seize this rare opportunity to shape public education’s destiny by insisting on the kind of transformative redesign of education that comes reluctantly to our notoriously hidebound school systems. We have an opportunity to step back into the messiness of this crisis and reassess how we are seeking to achieve our broader education goals: How do we ensure that each student is successful? What is success, and how do we measure it? What are the preconditions in the lives of children that must be in place in order for them to be ready to learn in optimized schools? What kind of school time (calendar, schedule), resources, integrated human services and enrichment systems will be necessary to fill in all the critical gaps so that we can build that pipeline to success for those not fortunate enough to be born into it?

Our field must take the lead in shaping a 21st century conception of what America seeks to do for its children — and how we get that done. Otherwise, at best this is a missed opportunity; at worst it will be a step backward with a whole bunch of misguided ideas thrust upon educators in the process. To project a radically broader vision of what it takes to ensure children’s success will require courage in challenging the status quo, which current leaders are usually expected to defend.

This won’t be easy. However, only in this way, with such a vision and bold leadership, can we take full advantage of the opportunity that this crisis presents.

Paul Reville is a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where he leads the Education Redesign Lab. He is a former Massachusetts secretary of education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)