Rethinking Kindergarten for the Pandemic: With Colorful Masks and Many New Rules, Mrs. Hogan’s ‘Honeybees’ Arrive for Class in Texas

This article is published in partnership with TexasTribune.org.

Just after 9 a.m. on their first day of in-person learning, Mrs. Hogan’s “honeybees” turn to one of the most important tasks of the year: drawing self-portraits.

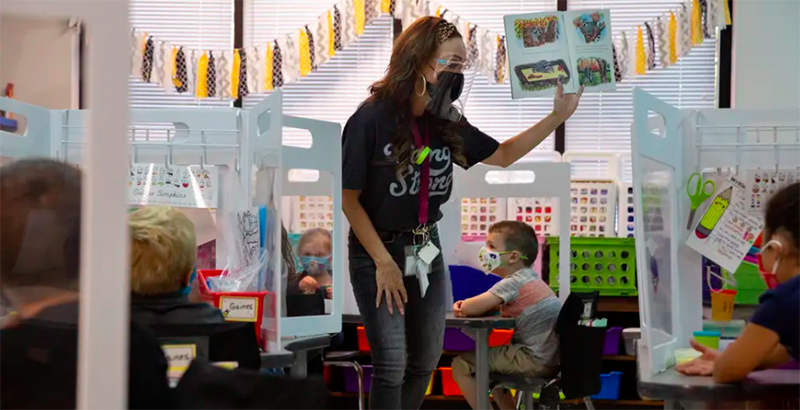

“Are we going to draw ourselves itty-bitty tiny?” Hogan, a petite woman wearing leopard sneakers, a black mask and a pink rhinestone face shield, asks the classroom.

“No!” chorus back 16 kindergartners.

“Mrs. Hogan wore her best face shield and mask today,” she continues, sketching her own portrait on a projector at the front of the classroom. “So when she draws her face, is she gonna draw her mask?”

“Yes!” the class bellows back. She moves on — How many arms should Mrs. Hogan draw? — as two boys in the back of the classroom discuss, through the clear, three-sided shield dividing their desks, whether to include eyelashes.

The class helps Hogan count out how many fingers she has on each hand. At the projector, she draws a cylinder next to her hand. “And I brought my own water bottle because we’re not gonna use the water fountain,” Hogan says, reminding her students gently of a new rule. By the other hand she draws her leopard lunch box.

A little boy named Levi, of the eyelash debate, sketches his spiked-up, first-day-of-school hair in pencil, then goes in with a red crayon for his T-shirt and black for his mask.

Tuesday marked something of a first day of school for hundreds of students at Highland Village Elementary, where most families opted for in-person instruction when Lewisville Independent School District, one of the state’s largest, returned to classrooms this week. The district began classes in August with three weeks of remote instruction, delaying an on-campus start like many districts in the state.

It’s harder to smell fresh pencil shavings through a mask. But the new sneakers were still first-day white, the lunch boxes proved stylish and well-stocked, and the masks — printed pink, Polly Pocket, standard surgical, pepperoni pizza, rainbows, Mickey Mouse — mostly stayed on.

For Angie Hogan, 46, a longtime kindergarten teacher who wants to teach 5-year-olds until she retires, it has been an adjustment, but not an impossible one.

She arranged desks into pairs, separating them with clear shields. There is no carpet at the front of the room where kids can gather in a circle to talk, there are no stuffed honeybees to hug, and there will be less close interaction. So Hogan is taking care to build community in other ways, and she is helping kids get out their wiggles by dancing to choreographed YouTube videos as they stand at their desks.

Hogan took the play money out of the play cash register and left the class’s plastic toy baby in just a diaper so there are fewer things to sanitize at the end of the day. This year there will be no sharing of supplies. Each student has a folder on the back of their chair, marked with their name and a honeybee, and a basket with individual markers, pencils and Play-Doh.

That’s been hard — because “kinder is all about sharing — learning that skill,” she said. “And I’m a hugger, so that’s been the hardest thing for me.”

Hogan has a daughter with type 1 diabetes who is also returning to school in person. Hogan acknowledged the risks but said it’s the best thing for her daughter.

The vast majority of Highland Village Elementary parents made the same choice, earning it one of the highest in-person attendance rates in the district. Experts say children are less likely to suffer severe cases of the novel coronavirus than adults, though children can play a role in transmitting the virus. But there are also risks to depriving students of in-person education, especially those with disabilities or those who have trouble connecting online.

Kids and parents were more than ready to come back, said Principal Leslye Mitchell. Mitchell recalled watching through a window earlier this school year as a second-grade teacher, seeing her students pop up on screen for the first time, began to tear up. Families missed the social interaction of being in the classroom, Mitchell said.

That’s not to say there haven’t been hiccups. Third-grade teacher Sundra Cazares solved one problem when she bought a pop-singer-style microphone to speak into, ensuring that kids can still hear her through her Texas flag print mask, spread out as they are across her classroom. But she has yet to solve another: During her lesson Tuesday morning, desk shields were accidentally knocked onto the floor or clattered onto desks, imperfectly secured to the students’ workspaces. Velcro may be the answer.

Administrators are keeping hallway traffic traveling counterclockwise to minimize interaction when students first arrive in the morning, meaning fifth-graders who enter in the front of the building have to trace an almost complete lap around the school to reach their classrooms.

“School feels back to normal,” school counselor Erin Walter said. “OK, we have masks and shields, but we’re back. It’s school. It’s awesome.”

Administrators are also getting creative with the lunch schedule, stretching it out longer so that fewer students occupy the cafeteria at any one time. That means kindergartners are scheduled for lunch at 10:15 — really more like brunch, administrators joke — with a snack later in the afternoon.

So mid-morning on Tuesday, Mrs. Hogan’s kindergartners lined up outside her classroom, each standing on a numbered honeybee. As they traveled down the right side of the hallway — one foot on a white tile, one on a gray, she reminded them — the staff members beside them encouraged distancing, without much luck.

“Hold your bubble!” Hogan encouraged, both arms rounded in front of her as if she were holding a huge kickball against her belly. “Try not to touch our friends! Keep our space!”

But for the most part, the kids scuttled and staggered along, brushing shoulders and comparing lunch boxes.

The Texas Education Agency has instructed schools to maintain physical distance “where feasible”; in many districts, that is almost nowhere. The classrooms at Highland Village Elementary are big enough to keep several feet among desks. But it’s hard to keep 5- and 6-year-olds apart as they line up for recess or wait for their turn in the restroom. Hogan knows she must skip her signature hugs, but she has not been able to resist the occasional elbow bump.

Once in the cafeteria, the kindergartners clambered onto seats at long, rectangular tables, wanting to crowd beside each other on benches and lean over the table to chat. Teachers had to show them to sit at far ends of each bench, butts on spots marked with stickers, with only one side of each table occupied. Bought lunches were grab-and-go. Masks were eagerly discarded. Not everyone was hungry yet.

A little girl in a gray dress printed with bespectacled cats struggled to open her chocolate milk carton. Hogan stood over her shoulder, stopping herself from reaching for the carton. Instead she mimed the movements, instructing her student to stick a nail in here, tug that edge there. Eventually the girl succeeded and turned around to look for a straw.

At recess, kids stayed with their classes on the field, the playground or the basketball court. The school is following experts’ recommendation to keep students in isolated cohorts, so that should any fall ill, it will be easier to determine whom they may have infected.

The lower halves of faces peeked out as the kids ran through the field and tramped across the playground, some masks tucked into pockets or hanging around necks as they played tag. An entrepreneurial third-grader set up a business selling beaded mask straps, customizable with letter beads to spell out names. They held fast behind students whizzing by in long-overdue games of tag.

Later, in Hogan’s classroom, it was time to return to math. Three dogs had arrived at a park, then two more.

Some students had grown characteristically antsy. “Look, it’s windy,” one told his deskmate, making his clear desk shield sway back and forth.

In the early afternoon lull, masks came off or slipped down. Hogan chided the children to return them to their proper places, in the same voice she used to chastise those who spoke without raising their hands or failed to count along with her as she marked out five hops along a number line.

She wasn’t the only one enforcing safety protocols. A little girl named Ella, her water bottle marked with a cursive E, reminded a neighbor to pull her mask over her nose. The girls both wore pink masks and poofy pink skirts.

Returning to academics, Hogan walked around the classroom to check students’ work.

“One, two, three, four; num-ber five, shuts the door,” Hogan rhymed to a student who’d scratched out the correct five tally marks. “That’s fabulous work! Give me an elbow bump.”

Emma Platoff is a reporter at The Texas Tribune, the only member-supported, digital-first, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)