Response: What NPR’s ‘Hit Piece’ Got Wrong in Attacking Rocketship’s ‘Impressive Results’

The story did get one thing right. Our students’ “results are undoubtedly impressive.” But rather than dig in and really understand what underlies our Rocketeers’ impressive achievements, NPR’s blogger, Anya Kamenetz, went to great pains in trying to undermine our success and defend her personal anti-testing thesis.

Eliminating the achievement gap is hard work. As Paul Tough’s latest work highlights, it is particularly hard for people who have not worked or lived in low-income communities to understand the unique challenges of teaching in high-poverty schools like Rocketship. And I’m sure it was very hard for Anya Kamenetz to understand, as she herself did not visit a single Rocketship school.

If our schools are really what NPR’s blogger portrayed, the critical question she didn’t ask is: Why did 90% of Rocketship students return this year? They don’t have to enroll at our school. They have a seat at their zoned district school waiting for them. But they come back, year after year. And they tell other families to do the same.

In our most recent parent survey, 72% of parents stated that “I have recommended Rocketship to another family.” To be clear, these are parents who actually recommended Rocketship, they are not simply saying “they would recommend.” 2,276 parents responded to this annual survey. Sure, not every parent is happy every day. But most days, most parents love their Rocketship school. So much so that they tell other families to enroll.

Maybe as a Rocketeer parent myself I’m biased. But then again, why would the NPR blogger paraphrase the president of a local district’s teachers union who asserts that, despite low test scores, “their parents are happy” and then not ask parents like Salvador Ramirez and Jennifer Perez who have very publicly expressed their unhappiness with that district in their local paper of record?

A good portion of the NPR blog post calls into question the validity of our test results. “Former staffers” are quoted as getting repeated requests by teachers to issue re-tests. For the record, the “impressive results” the NPR blogger cites are on state assessments for which we are not able to issue a re-test without authorization from the Department of Education. Without their approval, the state’s online assessment system will not allow students to take a test a second time.

On the most recent state assessment in California, we had 6 students retake a single test out of 4,565 tests administered.

In regards to the NWEA MAP assessment that we administer to track student growth, we were well aware of the concerns expressed. But those issues are several years old now. Our policy and protocols on re-testing are clear: we don’t re-test students on the basis of their score. On NWEA MAP last fall, we had 16 retake requests out of 12,695 total tests administered. We approved 2. This past spring, we approved 15 retakes out of 12,706 tests administered. That is a retake rate of less than one tenth of one percent.

Those “four emails” that NPR’s blogger obtained referencing teacher requests (not approvals) to retake a test from two years ago is a far cry from the reporting rigor and journalistic integrity we expect from an organization like National Public Radio.

But for a moment, let’s just entertain the notion of “rampant retesting” that the story asserted. If our teachers were indeed gaming the system, once our kids move on to middle school (we only have elementary schools), their scores would logically plummet.

But in an independent study from SRI International, our alumni in middle school significantly outperform their peers. The gap-closing gains our graduates make in elementary school persist in middle school. NPR’s blogger does briefly mention this study, but not in the context of re-testing where the SRI study clearly dispels her assertion.

Bathroom breaks and silent time are cited as evidence of our behavior management practices gone awry. Anyone who has ever taught understands bathroom management in elementary school is complicated. Do accidents happen in our school? Yes. Just like they do in elementary schools every day in every community. Bathroom break decisions are best left to the discretion of our teachers and leaders, as they understand the unique needs of their individual students, class, and campus. Blanket policies on bathroom management are a bad idea. That is why Rocketship does not have any network policies on bathroom breaks.

I know how it feels as a parent and as a teacher when my child or student has an accident. But the two regrettable incidents NPR’s blogger references cannot be generalized to a network that serves almost 7,000 students. Parents know when their kids have an accident at school. If this were a systematic problem with all our schools, parents would not stand for it. Parents would rightly take their kids out of our schools. I am one of those parents. I send my own two children to Rocketship Fuerza Community Prep.

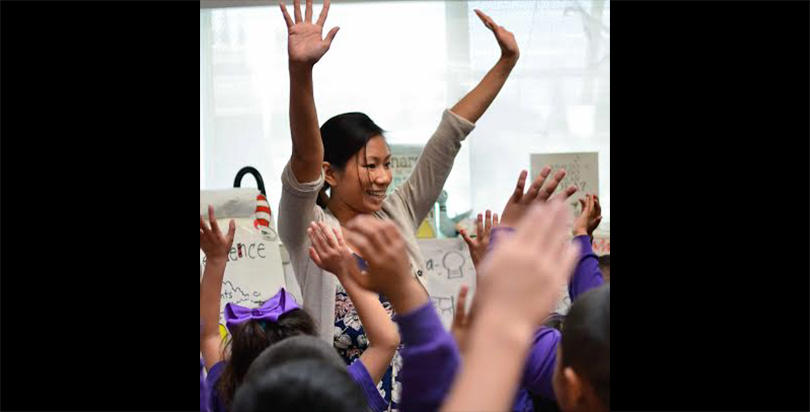

Silent time, what we call “Zone Zero,” was the other behavior management practice the blogger called into question. Are there times at school when kids need to be quiet, pay attention, and listen? Of course. Are there times when we encourage kids to interact with each other, dance, and just be kids? Every day.

Each morning, at every Rocketship school, the entire school gathers to recite our core values, dance, sing, and get motivated for the day ahead. We call it Launch.

When we hosted NPR at our school (again, not Anya Kamenetz), we watched Launch together. Not once during the school tour did the journalist notice or ask about “Zone Zero.” So why is Launch absent, and Zone Zero prominently featured in their blog post? The only identified source NPR’s blogger cited in her criticism of Zone Zero, Farah Dilber, reached out to me after the story published to express her frustration at how NPR misrepresented her comments. Farah wrote (shared here with her permission):

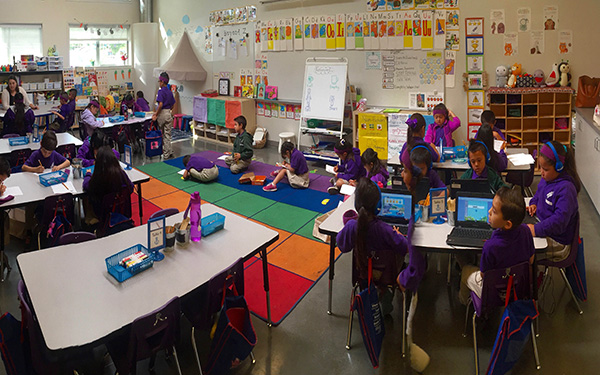

Rocketship was one of the pioneers of personalized learning in public education nearly a decade ago. We’ve taken a lot of heat for our use of technology over the years. But today, technology is pervasive in public schools and homes across the country. We need to get beyond just thinking about “screen time.” We need to engage in a more thoughtful discussion on technology for learning, like Anya Kamenetz herself did here. But why did she not take this “more mindful approach” to technology for learning in her reporting on Rocketship?

Putting that all aside, the story still grossly misrepresents our use of technology. NPR’s blogger conflated a response from DreamBox, regarding their recommended weekly use of their online learning program. DreamBox recommends that students spend “30-45 minutes per week” using DreamBox. The story then leaps to Rocketship students spending 80 minutes every day. This statement blatantly misleads the reader, given that those 80 minutes are spent across at least 5 different adaptive online learning programs — not just DreamBox as the quote inferred.

Furthermore, this Harvard study clearly states “Rocketship students spent an average of 44 minutes per week in the weeks they used DreamBox.”

It troubles me that we are still asking the simplistic question of “how much screen time?” Let’s unpack that question for a moment. Right off the bat, the question ignores access to technology altogether. It’s hard to imagine a parent whose kids have to go to McDonald’s for free Wi-Fi to complete their homework asking that question.

As a recent report on “Technology and learning in lower-income families” published by the Sesame Workshop states, “Because digital devices and the Internet have become so essential, digital inequality can exacerbate educational and economic inequality as well.” Without access to technology in our schools, many of our Rocketeers would not build the skills they need to succeed in the 21st century.

The other problem with the question “how much screen time?” is the implied presumption that all screen time is created equal. Any parent, really, any person, understands that some content is good for learning, some content is good for entertainment, and some content is not so good at all. Before my kids started school, I had no problem letting them watch Sesame Street. More than 1,000 studies have shown pre-schoolers who watch Sesame Street do significantly better on a range of cognitive outcomes. Similarly, we are very purposeful about the content we put in front of our Rocketeers.

No software program will ever match the impact of our exceptionally talented teachers, but rigorously developed and researched adaptive online learning programs like ST-Math, Lexia, and my son Zeke’s favorite, myON, provide valuable, differentiated learning time for our Rocketeers over-and-above the 6 hours they spend in the classroom every day.

To put it simply, our schools are nothing like the school portrayed in this story. If they even remotely resembled this story, why would I send my own kids to Rocketship Fuerza? Why would over 8,000 parents be sending their kids to Rocketship schools across the country next year? And where is their voice in this story? The voice of parents who show up in droves to defend our schools at reauthorization hearings? The voice of parents who drove over 100 miles every day to send their children to Rocketship, then organized parents to open a Rocketship school in their own community? And the voice of parents who are deeply engaged in the most important decisions of our school, like interviewing teachers for our first campus in southeast Washington DC?

Those are the voices we care about at Rocketship. As long as we continue to have their trust, stories like these, while frustrating, do nothing to take away from the remarkable accomplishments of our Rocketeers. Eliminating the achievement gap is hard work — it takes grit, commitment, and a willingness to think differently; all in an effort to succeed where countless others have failed. Our teachers, parents, students, and staff demonstrate enormous courage every day as they challenge the status quo. We know we are not perfect. Rocketship is still a work in progress, but the progress we are making in communities historically left behind is nothing short of transformational.

One last thing: While I am deeply disappointed that the NPR Ed blog published this story, my trust in NPR as an institution of journalistic integrity remains. If I learned anything about this experience, it is to not let the outliers undermine the integrity of an entire organization. This blogger clearly set out to write a preconceived story. She never even visited one of our schools herself. But as I told my team, do not let this lone blogger’s anti-charter bias cloud our perception of NPR as a quality news organization. NPR isn’t perfect, but like us, on most days, most of their work is nothing short of exceptional.

Preston Smith is Co-Founder & CEO of Rocketship Education, a non-profit network of public elementary charter schools serving low-income communities in California, Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Washington, D.C. He began his career as a teacher, later becoming a principal in San Jose, California. He lives in San Jose with his wife and two children who attend Rocketship Fuerza Community Prep.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)