Resolving the Pre-K Paradox: New Research Details How Chicago Filled its Preschool Classrooms with the City’s Neediest Kids

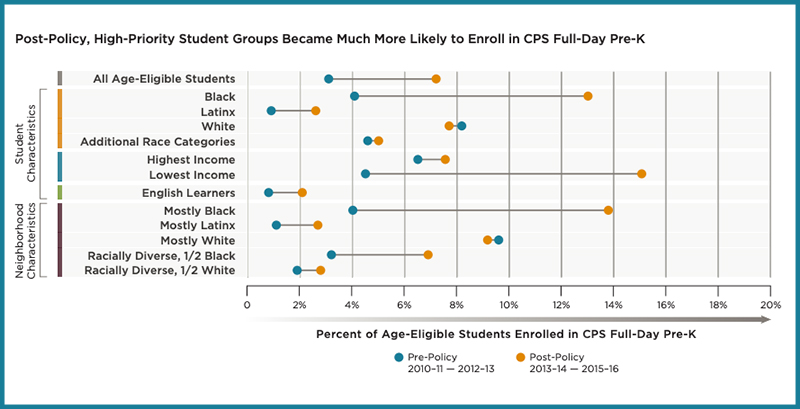

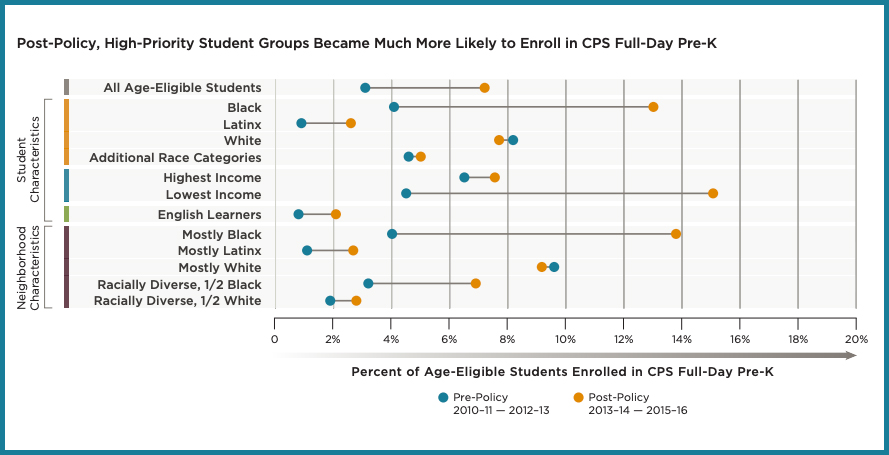

A series of policy changes begun seven years ago to help create more equitable enrollment in Chicago Public Schools’ pre-K programs has worked, according to education researchers at three Chicago organizations. Enrollment tripled among Black students and children from the city’s lowest-income neighborhoods, they found.

If the key factors — prioritizing full-day over part-time seats, concentrating them in historically underserved neighborhoods and centralizing enrollment — sound obvious, leaders in cities hoping to bolster their early childhood education system might want to examine the changes Chicago made.

With limited dollars to subsidize preschool and mounting evidence that the public’s return on investment is highest when resources are directed to the youngest learners, cities and school systems need to coordinate their pre-K investments to target the children who need them the most.

The organizations behind the new research are Start Early, an early ed advocacy and research nonprofit formerly known as Ounce of Prevention; the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, which has a longstanding partnership with Chicago Public Schools; and the data analysis institution NORC at the University of Chicago. The researchers looked at pre-K enrollment in the district from the 2010-11 school year through 2015-16.

Before the policy changes examined by the researchers, the students most likely to enroll in the district’s few full-day pre-K programs were white. Often, classrooms for 4-year-olds existed because a principal in a neighborhood where families could afford tuition would notify the school district there was demand.

In 2013, then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel — who controlled the appointed school board — began a systemic overhaul. City officials used census data to create a map identifying the neighborhoods where children needed early ed the most but were least likely to get it. They added full-day pre-K classrooms in the places that had the largest concentrations of disadvantaged families, often converting part-time programs that didn’t help working parents into full-time ones.

“They did a massive amount of data work to understand how the system needed to shift,” says Kristin Bernhard, Start Early’s senior vice president of policy and advocacy. “They had to make sure the classrooms were close to the children.”

Using census data enabled city officials to factor in things not typically taken into account when school enrollment patterns are determined, such as unemployment rates and parental education levels. (The researchers who produced the new evaluation also published an in-depth report on the methodology.)

“Those were factors in where we awarded classrooms,” says Bernhard. “If children come from the community, they’re likely to have the characteristics that are reflected in that data.”

Locating the classrooms near the kids was the single most important policy change, the researchers found, but multiple initiatives contributed to making the system more equitable. The city also created a single, centralized enrollment system, so district administrators could monitor whether kids were signed up in a manner that gave equitable access to all, not just to those whose parents had the time or ability to navigate the school system’s bureaucracy. The district can now hold seats for low-income students, children learning English and other kids most in need of pre-K’s benefits, and distributed fairly.

And leaders marketed the program at a grassroots level, making sure families knew it was free and that seats were available near their homes. Application assistants helped parents complete the process, sometimes nudging them via text.

Over the course of the six years researchers examined, the number of district pre-K seats stayed relatively constant. But the proportion of elementary schools offering full-day pre-K quadrupled, from 10 percent to 41 percent, and full-day enrollment rates grew from 3.2 percent in 2010-11 to 11.6 percent in 2015-16.

After the shift, the children most likely to enroll were Black, or living in predominantly Black or low-income neighborhoods. Enrollment of Latino children also grew, though at a much lower rate.

Next, the researchers will look at whether expanded access to pre-K in the district has an impact on early literacy. Bernhard predicts they’ll find the early start boosted children who graduated from the new full-day preschool classrooms, but cautions it likely won’t be enough.

“One year of pre-K isn’t going to solve our third-grade reading gap,” she says. “We really need to be thinking about learning from birth — and even before birth.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to Start Early and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)