Report: Black Children Lag in Key Educational Benchmarks in Michigan

Monique Stanton said that disinvestment in education has been compounded by a history of discriminatory policies.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

On average, Black children in Michigan are far behind their peers across the country when it comes to a number of criteria, including graduating high school on time, completing an associate’s degree and fourth-grade reading proficiency.

In fact, that was true of every benchmark measured in the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s new Race for Results report, which used data relating to early childhood, education and work experiences, family resources and neighborhood context.

“While our recent state budgets have gone a long way toward making sure schools are sufficiently funded, that’s coming on the heels of decades of disinvestment,” said Monique Stanton, president and CEO of the Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP), which houses the state’s Kids Count project.

Stanton said that disinvestment in education has been compounded by a history of discriminatory policies targeting housing, property tax limits and local funding for neighborhoods.

“Those years of inadequate funding means Black children in Michigan are among the least likely to attend preschool, be proficient in reading and math, graduate high school on time or earn a post-secondary degree,” she said.

First introduced in 2014 by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Race for Results was next updated in 2017. However, this third edition contains data from the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic that the MLPP says demonstrates the urgency of crafting policy prescriptions to ensure all children can thrive.

“Race for Results contends that young people are missing critical developmental milestones as a direct result of choices to not invest in policies, programs, and services that support children, especially in under-resourced communities and communities of color,” stated a news release.

While the report does note some metrics showing improvement in Michigan, it is uneven with some groups progressing and others continuing to struggle.

Michigan outpaced the overall national average when it comes to adults ages 25 to 29 who have completed an associate’s degree or higher. However, that progress is overshadowed by data indicating Black students were left behind, with just 20% earning that credential compared with 42% of Michigan’s young adults overall.

“As Michigan strives to grow our population and create a stronger sense of belonging for people who live in our state, it is critical that we address inequities through policy change,” said Stanton. “When it comes to funding and supporting education, we must make deliberate choices to make sure that the next generation of students has the tools and resources they need to get ahead regardless of race, ZIP code or income.”

Another area of progress in Michigan concerned children living in two-parent households, which MLPP says statistically have more resources and are more financially secure than single-parent households. While the increase applied to Black, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Hispanic children, as well as children who identify as two or more races, white children were the only group for which this indicator worsened.

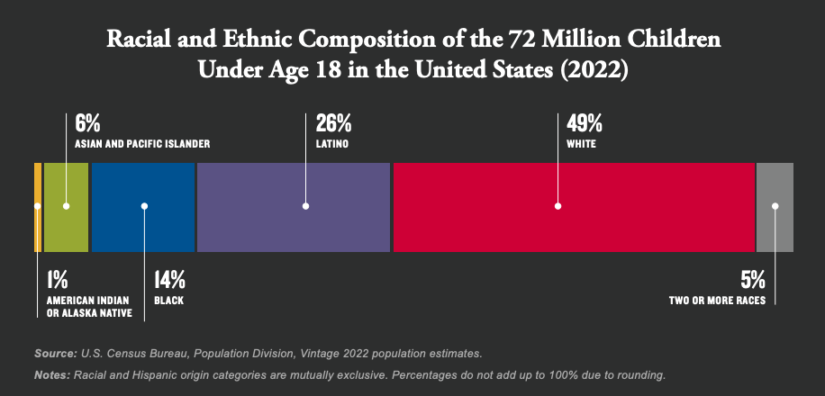

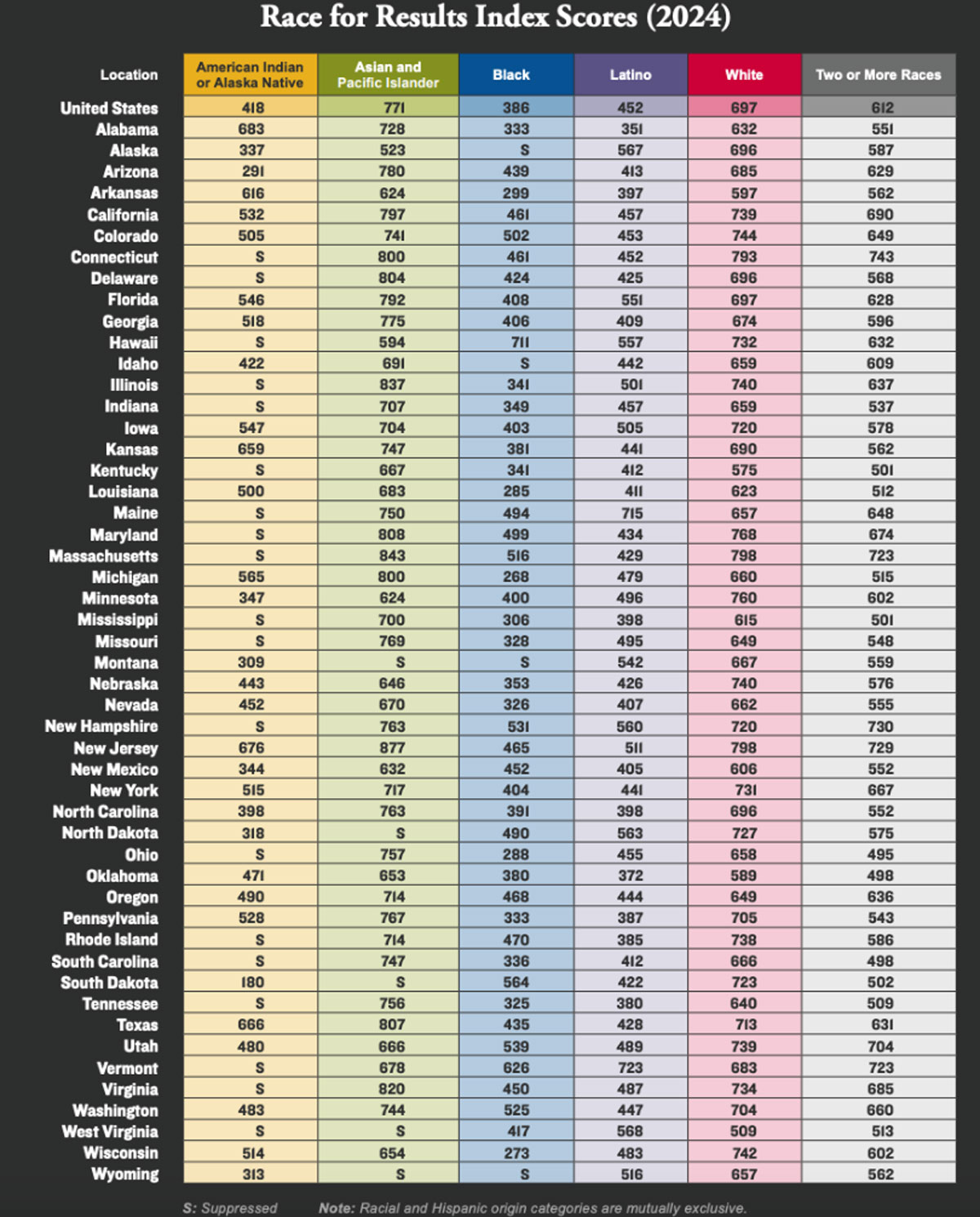

The methodology utilized by the Race for Results report standardizes scores across 12 indicators that represent well-being milestones from cradle to career. Those scores are converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 1,000 to more easily compare differences across states and racial and ethnic groups. Indicators are grouped into four areas: early childhood, education and early work experiences, family resources, and neighborhood context.

Michigan’s overall scores were as follows by race: (comparable national score in parentheses)

- Black: 268 – (386)

- Latino: 479 – (452)

- Two or More Races: 515 – (612)

- American Indian/Alaska Native: 565 – (418)

- White: 660 – (697)

- Asian and Pacific Islander: 800 – (771)

Across all 50 states, the index demonstrated experiences vary widely depending on where a child lives, from a high of 877 for Asian and Pacific Islander children in New Jersey to a low of 180 for American Indian or Alaska Native children in South Dakota.

“Young people are missing critical developmental milestones as a direct result of choices to fail to invest in policies, programs, and services that support children, especially in under-resourced communities and communities of color,” said a release by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

As an example of policy decisions that can have almost immediate impact, the report points to the time-limited expansion of the federal child tax credit initiated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. While most of the families temporarily lifted out of poverty were families of color, the policy also improved financial stability for families of all racial and ethnic groups.

“The expanded child tax credit’s success in providing a more stable foundation for children is an example of the innovative solutions American leaders can develop when they follow data and evidence and act with deliberate speed,” said the report.

Race for Results provides several recommendations toward improving outcomes for all children:

- Congress should expand the federal Child Tax Credit (CTC). The temporary, pandemic-era expansion of the CTC lifted 2.1 million children out of poverty, with the share of kids in poverty falling to 5.2% in 2021, the lowest rate on record.States and Congress should expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (Michigan did this in 2023).

- Lawmakers should consider baby bonds and children’s savings accounts — programs that contribute public funds to dedicated accounts to help families save for their children’s future.

- Policymakers must create targeted programs and policies that can close well-being gaps for young people of color, because universal policies are important but insufficient for continued progress.

Disclosure: The Michigan League for Public Policy contributes a regular column to the Advance.

Michigan Advance is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Michigan Advance maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Susan Demas for questions: info@michiganadvance.com. Follow Michigan Advance on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)