Nonprofit Bringing Businesses to Life in the Classroom — to the Tune of $400,000

Making candles out of crayons, building birdhouses, fashioning furniture: Real World Scholars has helped 50,000 students become entrepreneurs

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

Correction appended Oct. 26

Not much entices a second grader to skip out on recess to get back to schoolwork. But excitement around a classroom-run business can do just that, especially when it means creating candles out of crayons and selling them in the local community.

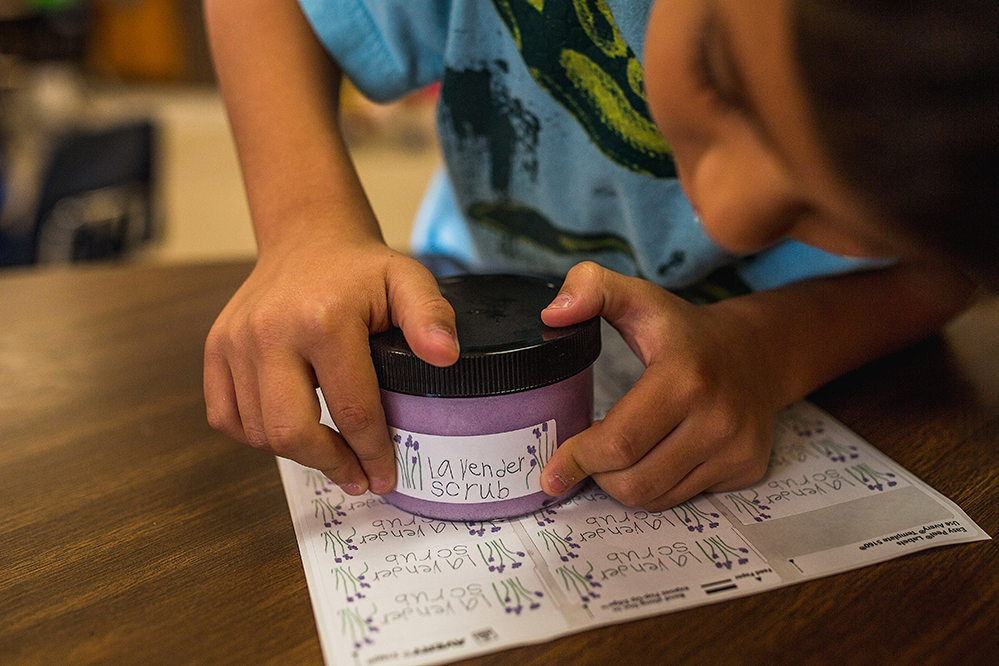

That’s just one of the businesses Real World Scholars has helped schools around the country set up, empowering teachers to spark their students’ entrepreneurial energy — whether it’s elementary school kids building birdhouses or high schoolers welding furniture. The nonprofit offers logistics and curriculum toolkits that give teachers a framework for getting a classroom-based business running and keeping it operating.

“I think student engagement and development of the entrepreneurial mindset has such big implications for everything else,” says Elyse Burden, co-founder and executive director. “When students want to come to class, it is a lot easier to teach them math. We are seeing improvement in the classroom culture, with impacts on learning, and workforce skills are being developed.”

Since starting in 2015, Real World Scholars has reached over 50,000 students from kindergarten through high school with roughly 600 student-led businesses in 34 states. Most sell to the local community, with students learning the art of setting prices and marketing along the way. Collectively, kids have made nearly $400,000, with much of it supporting local nonprofit organizations or being reinvested into the business. Some classes may make hundreds of dollars; others, thousands.

Each business supported by the program is directed by a teacher. Some teachers join the effort to give more direction to an already burgeoning idea, while others use it to get students excited about projects that incorporate an array of skills. Burden did not originally intend to create curriculum, but teachers appreciated having a basic toolkit to lead students toward identifying goals, learning business basics and walking through next steps. Teachers can follow the program — or not.

Once started, Burden says, successful classes break away from curriculum and let the unpredictable nature of entrepreneurship take its course, with motivated students helping to lead. “The experience explodes from there,” she says. “Students are connecting outside of school, and parents can get involved. It gives us an amazing opportunity to learn in a community based in a real-world way.”

The concept started in 2014, with Burden and co-founder John Cahalin looking to create a way to promote entrepreneurship inside core classrooms. “New legislation was talking about 21st century skills, with a lot of emphasis on soft skills, but teachers had no direction or support,” Burden says. “They were excited, but there was no mechanism.”

The first attempt to embrace that excitement, a press release offering half a million dollars to teachers wanting to run a business out of the classroom, was met with no takers — and questions about it being a scam. Burden says they realized that handling money in the classroom setting could be a “terrifying” proposition. Real World Scholars needed to provide infrastructure just to help give money away.

From there, they built a platform. It launched in the San Diego area with a chemistry class making and selling soap. The first year, they grew from 10 classes to 40. By the following year, more than 200 classes had participated. Today, the list of alumni includes a third-grade class in San Diego that built a “feel-good box” that acts as a care package, with chocolate, candles and more; a Wyoming woodworking and metalworks classroom creating art and furniture; and a Pennsylvania junior and senior high school that makes jewelry and floral arrangements.

Aaron Grable, digital arts media teacher and career and technical education department head at El Camino High School in Oceanside, California, has been on board from the start and says working with Real World Scholars provides the final link in the chain for his graphic and web design classes that double as businesses.

“Students don’t come into my class expecting just another hour-a-day, five-days-a-week class where they’re forced to memorize things and take tests,” he says. “They are alive and engaged, not only while they are in my class but after and before class and on weekends. They are constantly trying to figure out new and exciting ways to make our business larger and more productive.”

As the school year moves along, Grable says, his role becomes more managerial, with students running the class and the business. “They foresee and prevent problems, they manage their time and their customers and they determine where the money goes after they’ve earned it,” he says. “They’ve created the class website, the class logo, the prices that we charge, the services that we provide, our client list, all our paperwork in the process through which we get and keep clients.”

Whether it’s a smoothly operating high school class, such as Grable’s, or a novice class with a teacher new to the concept, Burden says Real World Scholars aims to take the scary out of the entrepreneurial process.

Originally, Real World Scholars helped match classrooms with grants (Harbor Freight Tools for Schools is the largest sponsor, although a variety of business-based and private foundations take part, especially to generate regional funding). But as more teachers became interested in the program, demand outpaced the grant funding. When the pandemic hit, Real World Scholars retooled its dashboard to craft a more digital-friendly environment. The pandemic reduced donations, so it built a license model that lets classrooms pay for the service rather than waiting for contributions.

Grable says he enjoys watching students grow in different areas and work together to help one another and lean on the strengths of classmates in a class that is about more than just learning how to design websites. “It teaches them social and civic awareness,” he says, “effective and persuasive writing, personal conduct, professional demeanor, math and finance and something they don’t feature in a textbook: confidence and pride in yourself.”

Correction: Harbor Freight Tools for Schools is the largest sponsor of Real World Scholars

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)