Reading, Writing, Woodworking: A St. Louis Hub for Teaching Girls Key Skills

'It is really cool to walk into a place and see a 12-year-old on power tools,' says Kelli Best-Oliver, former educator and founder of LitShop.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

On Tuesday nights, a small storefront nestled in central St. Louis welcomes a crowd of young girls who are yearning to get to work.

Some of them are in the alley out back, cutting through tough plywood with circular saws, while others are inside using impact drivers to join pieces of framework. Other girls will be stationed next to a laser printer, creating decals and decorations.

“It is just a symphony of chaos, but it’s amazing,” said Kelli Best-Oliver, who oversees the work along with a group of volunteers. “They’re all doing it relatively independently and, you know, there’s music playing, and it’s just this diverse group of kids. The culture that we’re creating here is something special.”

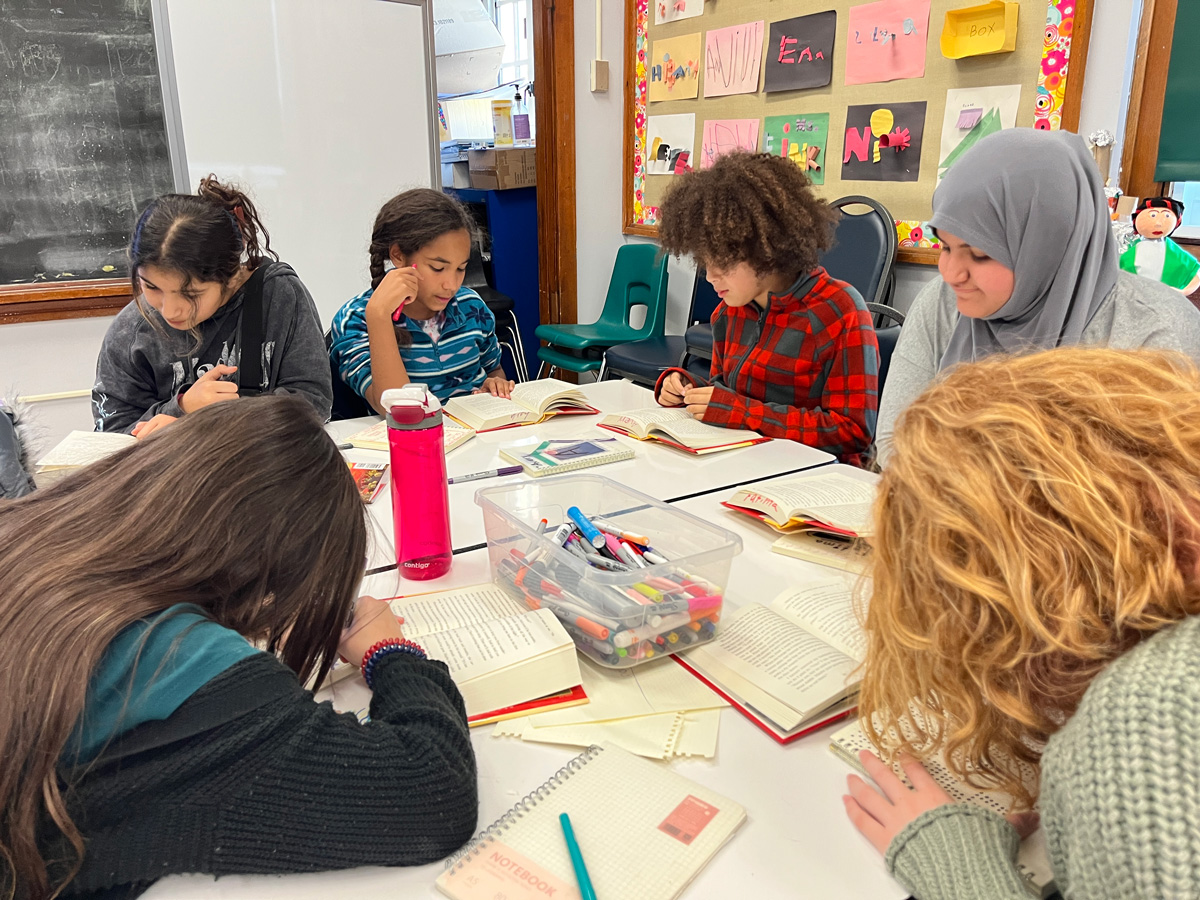

The project — building a structure for a hole of miniature golf — is just one of many happening at LitShop, a nonprofit that provides after-school and summer programming for girls and gender-expansive youth, ages 10 to 16.

LitShop offers book clubs and writing sessions along with workshops focused on building and construction — carpentry, printmaking, fiber arts or architecture.

Many of the resulting projects benefit the community. The miniature golf structure will go to a local arts association. The students also recently built a wheelchair ramp for a St. Louis resident.

“We will have kids who are attracted to us for one reason or another — they are either a bookworm or emerging writer, or they really want to get their hands dirty and make a lot of noise and learn how to use tools,” said Kelli Best-Oliver, LitShop’s founder. “It really opens kids’ eyes up to what they don’t even know because they’re not doing it at school.”

Best-Oliver, who worked as a literacy and language arts curriculum coordinator for St. Louis Public Schools for more than 15 years, said there are minimal opportunities in the city’s schools to take classes centered on construction and building. The push to pursue admission to college also discourages students from considering other options, like the trades industries, she said.

“We need to validate and affirm that building trades are just as valuable to both our communities and society, but can also be a tool for economic mobility. (Students) just don’t know because we’re not even giving them that information,” she said. “They don’t even know it’s an option for them.”

Female students receive even less exposure to the construction trades than boys, she said. That’s why LitShop is geared toward girls — to give them a chance to break into male-dominated jobs. Only 11% of workers in the industry are female, according to a 2021 report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Best-Oliver said it’s also crucial for LitShop to be open to gender-expansive youth, as LGBTQ+ people have an even smaller presence in the building trades.

“Especially in Missouri, it literally can save lives to validate a kid’s gender identity, in a safe and affirming place where they can be themselves,” she said.

Best-Oliver said she doesn’t want to inspire girls just to explore the trades industry, but also science, technology, engineering and mathematics. A lot of LitShop projects are STEM-based, such as a circuitry class the organization offered in early May. Students learned about wiring, batteries and circuits and how to make sculptures with LED-light fixtures.

According to the American Association of University Women, only about 28% of STEM employees in the U.S. are female.

Even if the girls don’t pursue a STEM career, Best-Oliver, said they will be gaining important skills for any path they take in the future. It’s “valuable and rad for girls to know how to use a circular saw,” she said. “It’s just a very powerful and empowering thing.”

For sixth-grader Stella Andersen, LitShop has given her an outlet for not only learning to use tools, but for exploring her passion for writing.

Stella has been with LitShop for three years and said she was initially attracted to its literacy component. One of her first projects was to read a novel and create a “twinkle board” — a large wooden sign with lights that spell out a specific word related to the novel.

She contributes to the organization’s publication, called LitMag, which features writing and art from the students, but also enjoys participating in group building projects like the mini-golf hole.

“It’s fun when people are walking by and they just look through the door and it’s funny to see them trying to figure out what LitShop is and what’s happening,” Stella said.

LitShop is based on a similar organization in Berkeley, California, called Girls Garage, which Best-Oliver visited in 2019. At the time, she was disillusioned with her job in the 20,000-student St. Louis district and frustrated with how test-driven curriculum was, especially in underfunded urban areas.

“When I walked in, I was just like, ‘This is it. If I don’t do something like this in St. Louis, someone else is going to do it,’ ” Best-Oliver said. “I was going to be stuck in my current job shaking my fist because I didn’t have the courage to strike out on my own.”

Emily Pilloton-Lam founded the California organization in 2008. At first, it was open to all students, but Pilloton-Lam shifted to focus on girls and gender-expansive youth in 2013 and changed the name to match.

When she created the organization, Pilloton-Lam said, she couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that even though the work was powerful, it was alienating the girls because they still felt like they didn’t fully belong working alongside the boys.

“It’s the thing that I have experienced as an educator, working with students, and I’m leading a build and I’m in charge and no one treats me like I’m in charge. I started to see some of those same feelings manifest with my female students,” Pilloton-Lam said. “I call it the social calculus of being a woman — you walk into a room or onto a construction site and you’re constantly having to calibrate, ‘How do I prove that I belong here?’ ”

Best-Oliver took her inspiration from Pilloton-Lam and created a pilot program of LitShop that started in St. Louis classrooms. She began by teaching students construction and writing skills in schools during the day, with the help of district staff. The pilot program was a success, and at the end of the school year, Best-Oliver quit her job to make LitShop its own organization.

The pandemic forced her to switch from in-person to virtual programming. The organization finally transitioned from being school-based to standing on its own after Best-Oliver purchased the building that now houses the storefront workshop.

LitShop currently has about 100 students enrolled, and Best-Oliver hopes to increase that number if the organization can secure more grant funding. All programs and workshops are free to students.

The nonprofit is gearing up to offer its summer programs: a print shop for making merchandise, like T-shirts; a woodworking and writer’s workshop; architectural model making; a furniture project; a book club; and a paper mache workshop.

“What we’re doing on paper can sound cool, but it can also sound confusing, like, ‘I don’t get how these things fit together.’ But if you come to our shop, and you see what we’re doing, nobody comes here and says, ‘This is lame,’ ” Best-Oliver said. “Everybody leaves here being like, ‘This is awesome. How can I get involved?’ We are doing something that nobody is doing. And it is really cool to walk into a place and see a 12-year-old on power tools.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)