Ransom: That C in Algebra Isn’t Just About Students’ Math Abilities, It’s About Classroom Environment, Too

As a new sixth-grade teacher in Chicago Public Schools, I created an “A’s and B’s Because I Tried” Club to recognize every student who achieved a top grade on a project. I had come to my classroom in 2004 the same way most teachers do: with an unwavering belief that students can achieve academically, with the goal of creating a classroom where every student felt valued and with the confidence that, if students tried hard enough, they would succeed.

Most of my students loved the “ABBIT” Club, and as I introduced each new assignment, they wanted to know, “How many points do we have to get to be a member?” The first time they asked this, I nearly burst with pride.

It wasn’t until recently that I looked back on this practice with something less than delight.

Research affirms that of all the outcomes schools measure, grades are the best indicators of whether a student will graduate from high school, enroll in and graduate from college, and live a long and prosperous life.

But what do grades actually measure? New research shows that grades — earning that B-minus in algebra, A in English or C in chemistry — measure something beyond students’ academic skills. Indeed, grades could be a measure of the social-emotional environment that teachers create. Research now shows that grades reflect students’ mindsets and learning strategies, and that the mindsets and strategies that impact students’ learning and grades are influenced by the conditions of their classrooms — the environments surrounding students on a daily basis.

We’ve always known that the same students can get very different grades as they take different courses or subjects, change grade levels or switch to a different school. The explanations have traditionally included the students’ own subject preferences and social distractions. However, research finds that students’ achievement across classes, subjects or grade levels is strongly linked to the mindsets and strategies fostered by their teachers. This means that what teachers do and say in their classrooms has a strong influence on how students experience school, their perceptions of themselves and the effort they put into their work.

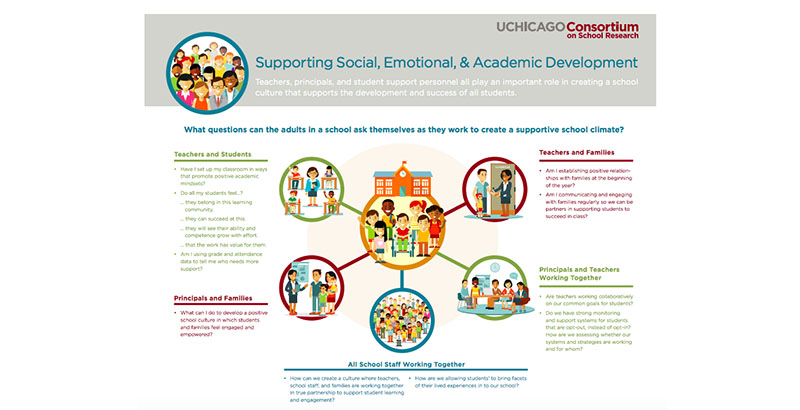

This suggests that if teachers can cultivate the right classroom conditions, they can promote strong academic mindsets and learning strategies in their students that contribute to strong classroom performance. A new student survey called Cultivate from UChicago Impact, a nonprofit affiliated with the University of Chicago’s Urban Education Institute, is designed to help teachers examine how the learning environments they create support students’ social, emotional and academic development — whether the conditions in their classrooms contribute to students’ development of the academic mindsets and learning strategies linked to higher grades.

Cultivate is grounded in a forthcoming study, to be published this year, from the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research that suggests reframing and refocusing our attention from “fixing” students — their actions, academics or social-emotional wellness — to helping teachers create environments where students can thrive, environments that can reinforce children’s positive beliefs about themselves as learners and actually shift their mindsets.

While I did not have the benefit of this valuable social-emotional development data during my time in the classroom, working on Cultivate served as a moment of reflection. Looking at the “teacher support” section of the survey, which focuses on how well a teacher actively and intentionally supports student learning, it was easy for me to say, “Of course I supported their learning!”

A deeper dive into what teacher support means, however, highlighted for me that to truly support students in deep and meaningful ways, teachers must attend to things such as:

● Helping students understand what went wrong when they made a mistake;

● Emphasizing that it is OK to make mistakes so they can learn from them; and

● Letting students know that it is more important to try than to get things right the first time.

My ABBIT Club started to feel like a series of missed opportunities. In execution, it did not emphasize that it was OK to make mistakes, and despite containing the word “tried” in its name, the club suggested that efforts to continually learn and improve were less important than getting it right. And, for my students who didn’t make the club, I did not properly allocate the time to support them in understanding the mistakes they made or address misunderstandings about the content itself.

Given the right data, teachers will gain the insight needed to more deeply reflect on how their daily practices — from the way their classrooms are organized to their use of culturally relevant content to influence students’ academic mindsets — ultimately affect academic achievement. Because there is a clear connection between the conditions that teachers create in their classrooms and the academic performance of students: An A in English or a B in algebra on a student’s report card also reflects how a teacher changes what students believe about themselves and, ultimately, how they perform.

Elliot Ransom is co-CEO of UChicago Impact. Previously, he taught sixth grade and worked at the central office at Chicago Public Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)