Pumped for Programming: ‘Hour of Code’ Highlights the Need for Computer Science Education

Brooklyn, New York

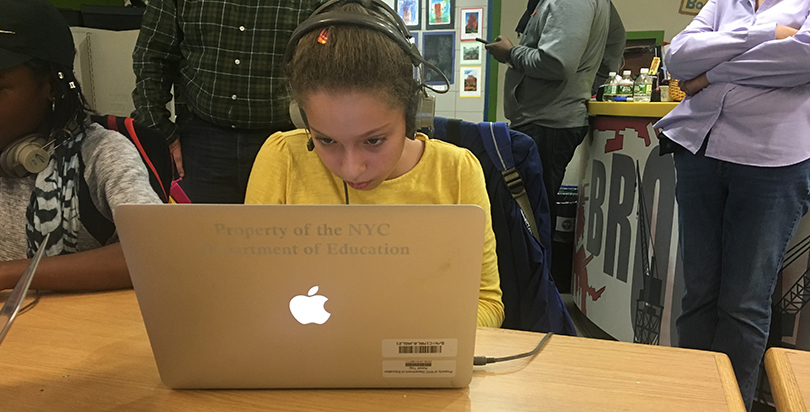

First, the 17 kids, a mix of third- through fifth-graders, had to choose how to display their names—in bright-colored, squiggly bubble letters or bold, block print.

Then the fun began. Using programming software called Scratch, they began to code, dragging and dropping blocks with commands to make the letters move.

One girl made the “M” in her name expand and contract, getting bigger and then smaller like a pumping heart. A boy figured out how to make the “E” in his name travel upside down across the screen. One enterprising student engineered a basketball player moving around in the background, a conversation bubble coming out of his mouth saying “Hello.”

“This is kind of like teaching kids fractions and algebra,” said Gordon Smith, CEO of Codesters, a programing education company and partner in the P.S. 15 “Hour of Code” event. “You take these basic skills and you build on them.”

The school’s assembly was just one of hundreds of pep rallies, code-athons and other events taking place around the world to celebrate “Hour of Code,” a campaign that coincides with Computer Science Education Week to introduce students to computer programming and encourage computer science education.

Now in its third year, the campaign, organized by the nonprofit Code.org, has reached some 300 million students around the globe who have spent at least one hour learning the basics of computer science, according to the organization.

Look at this room of #InformationTech HS coders!! @hadip @mrtomocon @weareci @codeorg @MelindaKatz @cornell_tech #CS4All pic.twitter.com/Tz1iQrqa0f

— Diane Levitt (@diane_levitt) December 6, 2016

The kids at P.S. 15 may not have known it, but they had just taken a step toward learning some critical life skills. As the hiring market continues to shift toward those with advanced technological knowledge, advocates say, introducing youth to computer science will become increasingly important.

Rather than focusing on traditional careers, “We should instead prepare all students for the jobs of the future,” Code.org founder Hadi Partovi told TechCrunch. “An ‘Hour of Code’ doesn’t prepare a student for a job, but it opens their mind about what they could be when they grow up, and that can make all the difference.”

However, growing from pep rallies and hour-long introductions to real, integrated computer coding or programming curriculums in the nation’s public schools has been a challenge. Only 33 states allow students to count computer science courses toward high school graduation, according to Code.org.

A survey released earlier this year by Google and Gallup showed that while 90 percent of parents in the United States think computer science education is a good use of school resources, only 40 percent of principals said their school offers a computer science class that teaches students coding or programming.

Black students were less likely than white students to attend schools with a dedicated computer science class and less likely to use a computer at home during the week, according to the research.

That problem has caught the attention of nonprofits, businesses and government leaders.

Even @CarmenFarinaDOE keeps learning! 4th grader George @ PS 241 in BK teaches her to code #CS4All pic.twitter.com/VDztaBNvYm

— Devora Kaye (@dskaye) December 6, 2016

In 2014, the Obama administration promoted the “Hour of Code” campaign when President Obama wrote his own line of code with middle school students from New Jersey.

“Part of what we’re realizing is that we’re starting too late when it comes to making sure that our young people are familiar with not just how to play a video game, but how to create a video game,” Obama said.

This year, Secretary of Education John King visited West Warwick High School and the Providence Career and Technical Academy in Rhode Island, where Gov. Gina Raimondo has announced that she wants every school in the state to offer computer science classes by 2017.

“We as a country ought to be looking to build on what’s working and expanding those opportunities,” King told News 12.

Many schools, however, are far behind when it comes to getting students access to even the most basic computer equipment.

Fourth Grade LOVES the #HourofCode #KidsCanCode #CS4All #CSK8 #CanWeDoThisAtHome? pic.twitter.com/Tg1nahjgti

— knives chau ??♀️ (@iwearthecrowns) December 6, 2016

For example, Brooklyn’s Brownsville Collaborative Middle School, located in one of the borough’s poorest communities, is just beginning to offer computer science education. This year, a nonprofit called Digital Girl has been teaching coding to a handful of students during lunch, according to Principal Alison Bassell.

“The fun thing about it is, it’s a game,” said Alicia Santiago, a sixth-grader in the program. “Kids like competition.”

The school received a grant through Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams’s office for 12 computers to create a lab for the students — but finding people to maintain the equipment has been a challenge. Bassell said that with more funding, she could expand opportunities for computer science education for the kids.

“Our students will be the future,” she said. “They will be driving the technology. Why not learn about it?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)