Proposal to Create Federal Autism Registry Stokes Fear in Disability Advocates

Culling data from medical records, pharmacies, genetic tests, even smartwatches raises specter of lists Nazis used to kill hundreds of autistic kids.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This week, National Institutes of Health Director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya sent shockwaves through the autism community by announcing the creation of a “disease registry” to track autistic people. Nazi Germany used such a list to identify possibly hundreds of autistic children to be killed in experimental “euthanasia” clinics.

Until the 1970s, numerous U.S. states used registries to identify disabled people to be subjected to forced sterilization and institutionalization. A number of states still maintain lists of autists.

“The history there is deeply, deeply disturbed,” says Larkin Taylor-Parker, legal director of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. “It doesn’t usually end well for us. It has ended in murder — industrial-scale incarceration and murder.”

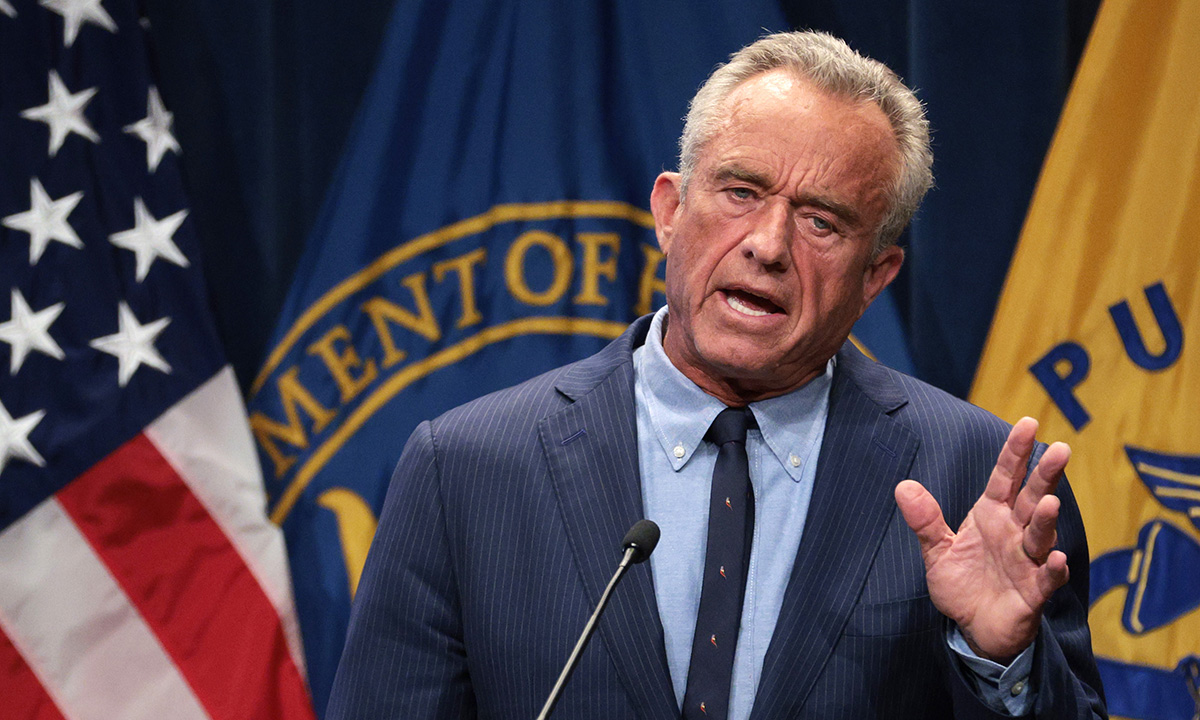

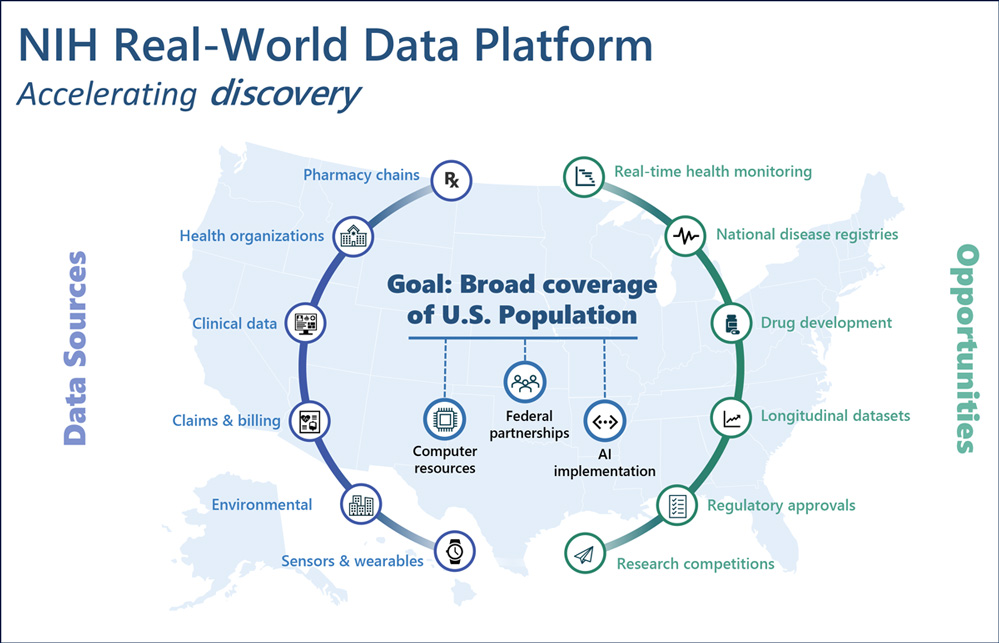

In a presentation given to NIH leaders April 21, Bhattacharya said the registry will draw from an unprecedented compilation of public and private databases to be used for U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s controversial new study of autism. In addition to information collected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the registry and research database will include pharmacy records, private insurer claims, lab and genetic testing information, treatment records from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service — even data from smartwatches.

Though the plan described is still too vague for advocates to know for sure, NIH might also tap state records that identify neurodivergent children who receive special education services. In the 2022-23 school year, almost 1 million autistic students attended U.S. schools.

Bhattacharya promised “state of the art” protections to guard patient confidentiality, explaining that 10 to 20 groups of outside researchers would be allowed to use the data but not download it. It is unclear whether this meets any legal standard for privacy safeguards.

As The 74 has reported, the man tapped to lead Kennedy’s study was found to have practiced medicine on autistic children without a license, prescribing a dangerous drug not approved for use in the U.S. and improperly giving them puberty blockers.

Kennedy, a longtime anti-vaxxer, intends the study to find a link between autism and vaccines. More than two dozen studies have discredited the notion of any connection.

With few details released about how the NIH will compile data — some of which is subject to privacy restrictions at various federal agencies— it’s unclear how patient confidentiality will be maintained.

NIH researchers are not bound by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, the main law that restricts who can access private medical information, and under what circumstances. Instead, the institutes must adhere to the Privacy Act of 1974, which protects “records that can be retrieved by personal identifiers such as a name, Social Security number or other identifying number or symbol” and, with limited exceptions, “prohibits disclosure of personally identifiable records without the written consent of the individual(s) to whom the records pertain.”

The privacy law was enacted in large part to stop federal agencies from sharing damning information about people singled out by former President Richard Nixon and former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover as political enemies. Since President Donald Trump’s second inauguration, privacy law experts have expressed alarm that Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency has gone into sensitive government records systems without legal authority to do so. Some courts have ordered a stop to the practice.

“The thought of a federal registry of autistic people that includes incredibly personal data that makes us very easy to find deprives us of the privacy that other citizens enjoy,” says Taylor-Parker. “It taps some of my community’s deepest fears and the specters of some of the most horrifying episodes in our history.”

In the 1930s and ’40s, German and Austrian public health officials reported the names of “malformed children” to the Third Reich’s Ministry of the Interior for a list of those targeted for sterilization or death. Among those supplying names was early autism researcher and Nazi collaborator Dr. Hans Asperger. He identified nearly 2,700 children, most commonly citing “education problems” as the reason.

Until 2013, Asperger’s Syndrome was a diagnosis given to autistic children who were believed to be “higher functioning” — Asperger himself called the visibly intelligent children he experimented on “little professors.”

Most advocates now recognize efforts to distinguish higher- and lower-functioning autists as false and harmful. In his presentation to NIH staff, however, Bhattacharya said the new research will consider the perceived severity of subjects’ autism.

“I recognize, of course, that autism, there’s a range of manifestations ranging from highly functioning children to children that are quite severely disabled,” he said, according to CBS News. “And of course, the research will account very carefully for that.”

This, too, terrifies Taylor-Parker, who notes that autistic people who are nonverbal or also have a developmental disability have historically been involuntarily placed in asylums and other facilities and are still often excluded from general education classrooms.

“We already have a societywide problem…with ignoring the support needs of people who can hold down a job, can drive a car and maybe score well on an IQ test,” she says. “On the other hand, we ignore the capacities, the capability, the humanity of people who don’t do those things.”

Further, she points out, compiling as much diagnostic and prescription information on autistic individuals as possible is likely to uncover other private information that people fear could end up on future “disease registries.”

“I’m very concerned about this becoming a slippery slope,” says Taylor-Parker. “There is very good research demonstrating that [autistic people] are trans and gender-nonconforming at above-average rates.”

In the interest of establishing the prevalence of autism and in some cases understanding which services are helpful, several states and two national philanthropies already maintain registries. With a goal of ensuring that as many children as possible are offered early intervention services, at least two contain identifying information.

Good intentions notwithstanding, many autistic people oppose the existence of any registry, citing the historical danger they pose for disabled people in general. Indeed, recognizing this last year, New Hampshire lawmakers eliminated the state’s autism registry.

Since Kennedy’s appointment, autistic people have repeatedly decried his plan to again attempt to link autism to vaccines, despite dozens of credible studies that have ruled out immunizations as a cause. His plan, they charge, would divert resources from research into therapies and services that can improve the lives of people with disabilities.

Says Taylor-Parker, “That discussion sucks the oxygen out of the room when it comes to making life better for autistic people who are already here and who will be born in the near future.”

According to the NIH, video of Bhattacharya’s presentation will be posted in the coming days.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)