A Former Journalist Reignites an Intergenerational Haven For Portland’s Youth

She once fled Oregon, her teenage home. Now, S. Renee Mitchell has etched out a safe space for generations to heal from trauma through art & community

By Marianna McMurdock | July 6, 2022This is one article in a series produced in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project, spotlighting educators, mentors and local leaders who see community as the key to student success. See all of the profiles.

A rare silence in a first grade classroom changed S. Renee Mitchell’s life.

To learn names as a guest artist, Mitchell prompted students at Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary in Portland, Oregon to pair their intros with an adjective, something they liked about themselves: “Brave Brian”, “Kind Kyla”. A quiet pattern in body language emerged: Black students dropped and shook their heads.

“I kept seeing it over and over and it was just like, Oh, what’s happening? The Black kids are not able to identify something positive,” Mitchell said, her eyes brimming as she spoke. “I still get emotional about it. Because it reminded me of me. I was a kid who couldn’t tell you positive things about myself because I didn’t hear positive things reflected back, not even in my household.”

At the time, Mitchell did not consider herself an educator. She’d been working with Portland schools as a way to connect with her community after leaving The Oregonian — where she worked as a Pulitzer Prize nominated columnist. Still, that evening, the career journalist wrote what would become a semi-autobiographical children’s book: The Awakening of Sharyn: A Shy & Brown Super Gyrl.

It’s a tale of how a young person can come to love all of themself, especially the parts others seem to disagree with. Through words, Mitchell found a way to model how to heal from pain and build a positive self image — the purpose she would dedicate her life to in the decade that followed.

She shared a draft of her children’s book with that group of reticent first graders, hopeful they could realize their brilliance young and maybe skirt the feelings of depression and fear that she felt for so long. By talking about her own feelings of shame and isolation as a kid, she opened the door for youth to open up without fear of judgment; shed their shame.

She then facilitated what would be the first of many ‘Superhero Awakening Ceremonies’ at a community center. The space filled with color, glitter and exclamation as children illustrated what they loved about themselves on capes, masks and paper. Parents were invited into the classroom to celebrate and sing an empowerment song: “Thank you superhero, I think you are amazing. I love you, superhero. You have so much style, you make me want to sing.”

What would have been a lackluster introduction exercise transformed into an outpouring of love for the young people who needed to hear it. And in seeing them, and their pain, Mitchell helped them engage differently in the classroom.

It was one of many experiences Mitchell now has of prompting herself and others across generations to come together and use art as therapy.

A self-described Creative Revolutionist, she imagines what art-inspired events or connections are possible, rather than what’s established and “allowed to happen.” She began hosting middle school poetry slams and family Write Nights, where parents and caregivers worked through prompts with their children.

“All of this for me is interconnected, it’s intergenerational. So yes, I love working with youth. It’s what I specialize in,” Mitchell said. “But it’s not the only thing that I do. Because in order to really have an effect on youth, you have to have an effect on community. And at the end of the day, I’m trying to do what was never done for me.”

Her approach — “I have an idea. Let’s just keep rolling with it till the wheels fall off,” — got her noticed by the then principal of Portland’s most diverse high school, Roosevelt. She was recruited to teach and stayed on for four years as the only Black educator.

“I taught journalism, but it was also like, how can I mother? How can I treat these like my own children?” she said. “How would I want them to be seen in the classroom? And that’s how I behaved.”

She’d start her days sourcing leftover bagels and bananas for students who came to school hungry and carved out class time for poetry, reinforcing for young people, “you don’t have to do or present things in the way people expect.”

Mitchell founded Roosevelt’s first Black Girl Magic Club with funding from the city’s Office of Youth Violence Prevention. Young girls gathered to dance, coexist; process their families, relationships and what it meant to be Black in Portland. She encouraged them to explore poetry as a medium — for its ability to make pain into something beautiful and allow the mind to wander.

In 2018, three of the four winners of Stand for Children’s $16,000 “Beat The Odds” scholarship were members of Black Girl Magic Club. Their applications, one of which was submitted as a poem, explored trauma and their sense of self. After some of them performed their stories at a MLK celebration, adults approached them in tears: they felt seen, wished they could be as brave, and wanted to celebrate them for their vulnerability. They were stunned that their personal stories were impacting people in ways they hadn’t imagined.

Mitchell was determined to hone the success into something greater for more of Portland. And after four years as a teacher, she also felt more could be done to support her community outside of the traditional school system than within it. She also decided to pursue a doctorate degree in education at the University of Oregon, and began training teachers and community members about how to help Black children heal from racial trauma.

Acknowledging — not hiding from — traumatic experiences became the seedling for her youth leadership development nonprofit, I Am MORE: Making Ourselves Resilient Everyday. Founded in 2018, I Am MORE has earned three social emotional learning awards from the New York based NoVo Foundation, and Mitchell’s impact was formally recognized when the city named her their 2019 Spirit of Portland winner. Each summer, the organization hosts a paid leadership training internship where youth discuss financial literacy, colorism, toxic masculinity, racial trauma and other life issues.

“Everything that we do is based in empathy. That’s why sometimes it doesn’t work in classrooms, because the teachers don’t necessarily have empathy for these kids. They might have sympathy — that’s not the same thing… not, ‘Oh, I feel sorry for you.’ But ‘Oh, I relate to you. Oh, I want to be able to be of service to you.’”

Dr. S. Renee Mitchell

“We help young people understand that they are MORE than the worst thing that has ever happened to them,” their website reads. To this day, the work mirrors Mitchell’s instincts with the shy first graders at MLK: recognize pain and create ways for young people to heal with each other and the adults around them. I Am MORE cohosts everything from open mic nights, where some teens just listen quietly, to camping trips focused on human connection.

The impact is felt inside and outside of the classroom: young people learn to express and advocate for themselves, in classrooms, at home, or in relationships.

“My work as an artist in the schools… helped me understand everything that I’ve done started with trauma. It was me seeing those kids, connecting that with my own trauma, and then trying to figure out — how do I make something out of that?”

The process once saved Mitchell’s own life. She began processing her childhood, sexual assault and domestic violence through poetry and playwriting as a young adult.

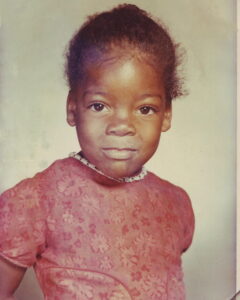

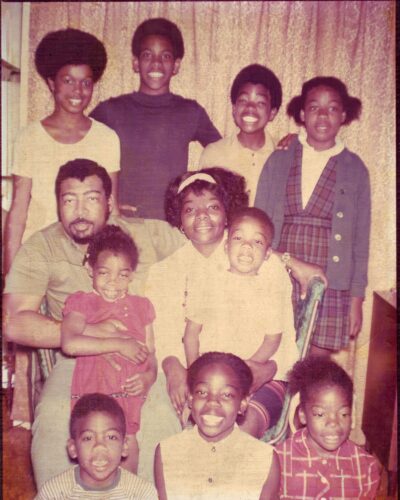

The middle child of eight siblings and a miscarriage, Mitchell grew up unseen and misunderstood. Often the only Black student in her Northern California and Oregon classrooms, she was frequently isolated and bullied, including at home by her brothers. While her father, an educator and community activist himself, introduced her to Black thinkers, history and social commentary early on, he passed away suddenly when Mitchell was 11. Ever since, she yearned for a “reconnection” to the positive roots she associated with his stories, work and sprawling library.

“When youth experience something, they feel like this is the first time this has ever happened, and it’s only happening to them. And so I was really clear about some of the trauma that I experienced and the death of my dad — how that after that I started thinking about suicide,” she said.

“Even though I was smart, even though I was obedient, even though I was a great cleaner, even though I did everything I was supposed to do, I still was miserable and depressed and overlooked and suicidal and no one really paid attention.”

In high school, a biracial student that Mitchell tried to befriend said she had to cut ties, lest she be identified with being Black, too. The isolation and harm from predominantly white environments was an accepted reality that followed her until she attended a historically Black university.

Though she felt liberated at Florida A&M — for the first time, surrounded by Black joy — in her first semester she was raped. Two years later, an abusive partner emotionally isolated her and repeatedly threatened to shoot her friends. The violent partnership stirred up previous suicidal thoughts.

“I sat on the bed and I got his gun from the closet on the top shelf. And I sat on the bed, and I put it to my head. And then I was like, ‘What am I doing?’”

“That was a turning point for me. And it also helped me have a depth of compassion for youth who may be going through the same thing and don’t have that thing that shifts — that moment,” she said, donning a silver chain that reads ‘resilient’. “Everything in me is fighting for that kid.”

Mitchell, who also survived domestic violence in her second marriage, talks about her trauma often, through poetry, playwriting and performance. After speaking for a community college class, one student responded with an essay: her abuser trained her not to talk. After hearing Mitchell’s story, she felt granted “permission” in a way, to process and heal from what happened.

Mitchell keeps notes like these, and student art, within an arm’s reach at her home desk. She says they are reminders of her purpose, why her life led her back to weaving her community together in Portland. In the last year alone, I am MORE has partnered with other organizations to orchestrate art galleries, Black power movie nights, quilting and financial literacy workshops.

“This is not a job for me. This is a life path because of the trauma that I experienced. Because of the many times where I felt like my life is worthless. And understanding as a teacher, so many kids are going through this same thing every day,” Mitchell said. “They just need someone to see them in that moment and remind them of who they really are.”

Craving a place of belonging

Mitchell is chipping away at the walls between communities in Portland, the same place she and her sisters hated so much as ostracized teens they graduated early to leave.

Racism is baked into the region’s history — in 1859, Oregon became the only state in the nation to explicitly ban Black people from living within its borders with an exclusion clause in its constitution. The city was fiercely redlined; Northeast Portland’s Albina neighborhood was established as a Black stronghold.

City projects decimated the community under the guise of “urban renewal.” Legacy Emmanuel Hospital destroyed 300 predominantly Black owned homes and some 30 businesses to expand. For five decades, an empty stretch of land remained — the Hospital never grew. Mitchell felt sick driving past the lot. A new Black-led project is now working to build affordable homes, a community garden and shared office space on a plot returned to the community by Legacy Health.

“Now, I have been accustomed to racism, but Oregon had a particular kind of racism. And I was like, I never want to live here again, I just want to escape,” Mitchell said, reflecting on her state of mind as she headed off to attend Florida A&M. In her teens, there were no gathering spaces or community experiences for Portland’s Black youth.

The same cannot be said today. The Soul Restoration Center is reviving a cultural icon, its building home to the former Albina Arts Center, a destination for young and old in the 60s and 70s. A hub of learning, dance, music and intergenerational joy, community members came to the Center to access free photography, Swahili and modeling classes for just over a decade.

Mitchell signed the lease in February as the pandemic wore on, taking responsibility for the Center’s next chapter from local jazz musician and professor Darrell Grant. With support from art curator Bobby Fouther and lifelong Albina resident Sunshine Dixon, Grant began the Soul Restoration Project and revived the Center’s place in the community in fall 2021.

Without adequate funds to keep the Albina Arts Center open, the institution so central to Black Portland had shuttered in 1977 – and would stay closed for years. Nonprofits like Don’t Shoot Portland attempted without success to buy and restore the space, now managed by the Oregon Community Foundation. While a feminist bookstore leased the space from 2006-2019, it remained mostly vacant, save the occasional community event, until Grant made it home to the Soul Restoration Project in 2021.

Residents describe a particular bookstore that mirrored Albina’s energy until 2012: Reflections, where they would run into neighbors, cousins, playing dominos, laughing and drinking coffee. A Black Cheers, in Mitchell’s sister Linda’s words, where everyone knew your name. Small but beloved.

The pandemic shut down events. Young people began telling Mitchell they hadn’t eaten, washed up, or brushed their teeth for days in spring 2020 because they had no motivation.

There was an acute need for a youth-centered community gathering space, one centered on mental health and wellness.

At the time, I Am MORE led hybrid programming at its coworking office space, but were constantly sushed for making “too much noise,” in the heat of conversation or laughter about their sexualities, hyper masculinity, colorism. They needed a bigger space to “show, to be ourselves,” safely.

“Not having access to those kind of spaces…you just don’t know how to ground yourself,” Mitchell said. “That’s the kind of thing we’re trying to revive…if I come here, my soul is going to be fed…I’m gonna walk away feeling better about myself and my connection to the community. That’s what’s missing in this very tiny Black community here in Portland, Oregon.”

‘It’s helping me get to where I want to be’

On a Friday afternoon in early March, Manny Dempsey, a 9th grader, gets settled in an armchair and flips through an early draft of his children’s book on an iPad. It’s a series of letters addressed to his unborn son.

He waits quietly for a publishing brainstorm with Elias Moreno-Lothe, I Am MORE’s “Vibologist” and youth director, who is DJing across the room, cohosting their weekly open mic night, Freestyle Fridays. The art mentorship, and atmosphere, is not something Dempsey can access at school.

“It’s not a place that I love but it is home,” he quickly says of Portland. When asked about the Soul Restoration Center, he flashes a smile. It felt like an art gallery the first time he walked in a few weeks before. It’s where he could pop in after school to meet generations of Portland artists and dream big about the children’s book that’s become close to his heart, a love letter to future generations.

“The space is really good to me. It’s helping me get to where I want to be in my future. I want to make comic books and share my art worldwide and not just in one space,” Dempsey said, sitting in the gentle sensory explosion that is the Soul Restoration Center at 14 NE Killingsworth.

Soft hip hop beats and the occasional Lauryn Hill are a constant, as are the sounds of a distant water fountain and faint smokiness from incense. Light from the front wall of windows showcases walls decked in Black art, ranging from humorous (a lifesize bronze LeBron James statue) to nostalgic and painful.

A central stage is framed by a large skylight — some of Mitchell’s artwork hangs in the center, tributes to ancestors that read “heal.” Tucked at the bottom of a shelf are a row of teddy bears.

Mitchell’s crew have decorated the open room to feel like home. Couches and close to a dozen rugs, a mix of mustard yellow, brown and red.

“We know that people are coming in tense. We know that they don’t have space to gather. And in every way we want to lower those defenses, particularly with our youth,” she said.

The city, wanting to bolster youth development in the wake of police violence and Black Lives Matter protests, allocated nearly $1 million to be provided annually by Portland’s Black Youth Leadership Fund. Mitchell became the fund’s first grantee, which enabled her to hire more staff, pay artists, plan citywide empowerment programming for the year and decorate the space.

Many describe the Center as one of healing, particularly necessary in Portland right now as hundreds grieve the loss of loved ones. In 2021, Portland experienced a huge surge in gun violence; 90 homicides were recorded, surpassing the city’s previous record of 66 and numbers seen in much larger cities like San Francisco. Black families were disproportionately affected.

Sunshine Dixon, who joined Mitchell’s team as a community connector after working with Darell Grant, came to realize Portland’s youngest are attuned to and looking for ways to address the violence. Outside of the North Portland’s public library, she and Grant provided art supplies and encouraged young people to work through whatever was on their mind.

One nine year old drew a man with a hole in his head, with bullets around the edges of the frame.

“I said, can you tell me more about this picture, and he said yeah, there’s a hole in this guy’s head because you have to have a hole in your head if you don’t believe there’s gun violence,” Dixon said.

“This place is also addressing black youth and recognizing that they need a place to come, they need a fugitive space, space to be. They need a place of healing. They need a place of safety,” she added.

Near the end of 2021, Mitchell began brainstorming more ways to meet the community’s emotional need to heal from violence through programming. “How can we not distract but give them something different?”

She invited a renowned quilter to lead a workshop and share the history behind her craft; during times of enslavement, Black women repurposed discarded food scraps, bags and clothing to make quilts.

Together Stitching Hope, Peace by Piece, partially funded by the City of Portland, was a hit. Most attendees were young Black men who had never sewed before; two became so interested that they went home with their own gifted machines. In Mitchell’s words, the workshop had “opened up something so deeply in them.”

“And that’s what I wanted to have happen — not to come to an event where someone says stop picking up a gun,” she said. “How can I redirect their energy towards something when they are in charge of their creativity?”

The Albina Center’s former dance floor transforms week in pursuit of that creative goal. In January, it became a theatre for a Black power movie night and discussion; a local rapper screened The Murder of Fred Hampton.

I Am MORE also facilitates signature fishbowl circles — a community building exercise centered on active listening. Youth start in the center, with elders surrounded in a circle. They’re prompted to share what they need that they’re not receiving, without interruption — observed like fish in a bowl.

“The young people get to speak and the people around them, all they do is listen. So the youth feel heard, they feel like somebody is paying attention to their opinion, what they have to say,” Mitchell explained.

When adults enter the center, they begin by acknowledging what they heard before offering up ways they might support or lessons from their own life. Strangers learn what they may have in common, and build a sense of understanding. Mitchell added the exercise helps older community members, who yearn for ways to share knowledge, to build a legacy.

The programming is an outlet for young people like Jolly Wrapper, now 20, who love learning and creating but dislike traditional school environments. Today, he works four jobs at local youth development nonprofits.

“I had the worst attendance rate out of my whole class… I was not good at high school, but I was good at jumping on opportunities. And using them as much as I could,” Wrapper said. He taught himself to play piano, use Adobe Premiere Pro for videos and perform spoken word, with the encouragement of Mitchell and Moreno-Lothe.

On Saturday mornings in March, yoga mats, journals and pillows filled the space as social worker, mother and wellness instructor ZaDora Williams hosted a support group for Black women.

“Baby, however you come, this is one place you can be loved on. You can create art with bullets, you can literally be you, that is what we are encouraging… We’re giving them language so that they can hopefully not re-experience the chronic health issues physically, mentally, spiritually that have plagued Black communities for generations,” Williams said.

Mitchell has curated the gathering space she, her siblings and neighbors craved as children.

She models nurturing behavior she expects her team to use — asking if they’ve eaten and providing food if they haven’t; making them write their own job descriptions so they have agency over their work; canceling meetings with city partners if youth don’t have a seat at the table.

Like her empathetic, creative reaction to quiet Black children nearly a decade ago, Mitchell leads with possibility and heart.

“At the end of the day, I behaved in a way I desperately wanted to experience while growing up. And my students recognized it as love, without me ever having to define it out loud.”

Updated June 7 | Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to both the Weave Project and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter