Pierce: Local Control of Schools Is Historically and Politically Important in Black Communities. State Takeovers Disempower Them

Despite a mixed record of results, state takeovers remain a popular strategy to address persistently underperforming school districts. Clearly, many local districts face challenges with student achievement and finance, and responsible state governments should not remain idle when the education of our young is impeded by operationally impaired schools. It’s debatable whether states consistently have the ability to address and correct deficiencies in local school governance, and much of the criticism is just on that point — that student achievement shows no signs of measurable improvement following a state takeover.

But state takeovers raise another issue of keen interest in urban education: The removal of local control disempowers local representatives from their elected governance of public schools. In some cities, this is emerging as an issue as charter schooling expands as well. You do not often hear this discussed at education conferences — although it was a topic at the Southern Education Foundation’s Issues Forum in Little Rock, Arkansas, in November — but it carries particular sociopolitical significance for some communities, given that state takeovers are largely visited upon school districts with large populations of African-American and Latino students.

Local governance of local schools consistent with state and federal education policies is an invaluable reflection of the underpinnings of our republic. The concept was an important component of the mass education movement in the years following the Revolutionary War and, more importantly, in the decades following the Civil War, as leaders worked to expand educational access to communities that had traditionally lacked schooling. Leaders of the 19th century education reform movement, such as Horace Mann, conceded the need for local control within state-authorized and -sponsored systems of mass education. Many reformers in the postwar South operated within the same framework.

Today, successful community school models trace many of their values back to the concept of local control and support of public education. I believe that most people, even those who favor school choice, want their children educated within a system influenced by their community. Overall, however, this community influence is largely framed within traditional governance structures, with a democratically elected school board representing the people of the community where the schools are located. This valued community connection is eliminated upon the execution of a state takeover of a local school district. And in African-American communities, these state takeovers are deconstructing hard-won black political power.

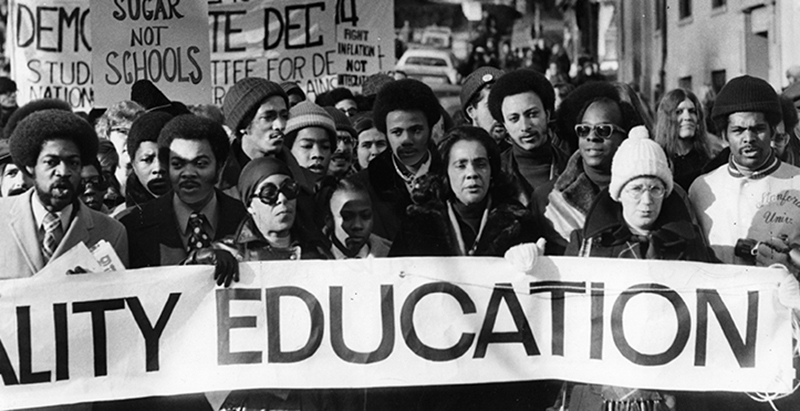

As time passes, too many people forget that school board elections were some of the first democratic processes in which African Americans were able to engage themselves as candidates for positions of public governance. In representing their communities on local school boards, African Americans were immersed within the political processes of city and county governance, which provided training for elevated levels of government service such as city councils, county commissioners, state legislatures and city mayors. Indeed, representation on local school boards was a key part of the school desegregation strategies during the black civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

There are long lists of African-American political figures who initiated their government service as elected community representatives on local school boards. State takeovers of local districts sever these ties and disconnect the long-held value of community influence, as well as inflict severe damage on a structure of government representation that has for decades prepared African Americans for greater government service.

In our urgency to address school district dysfunction that threatens the educational needs of our young, we must be attentive to the collateral damage that drastic actions may cause and to how, in the process, well-intentioned reforms can turn possible allies into adversaries. Right now, this caution is being disregarded, putting important strategies at political risk.

Raymond C. Pierce is president and CEO of The Southern Education Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)