Pa’s K-12 School Nurses Treat More Than Scrapes and Bruises. And They’re Asking Lawmakers For Help

With increased health needs, should Pa. update school staffing requirements?

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

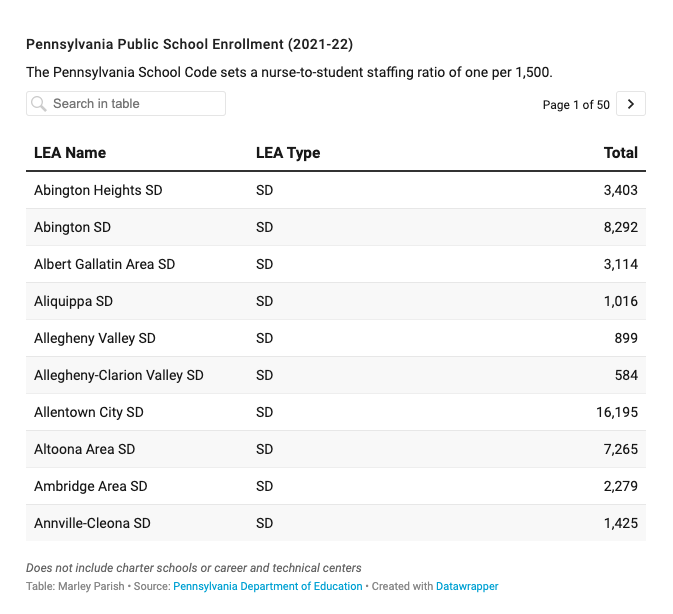

One per 1,500.

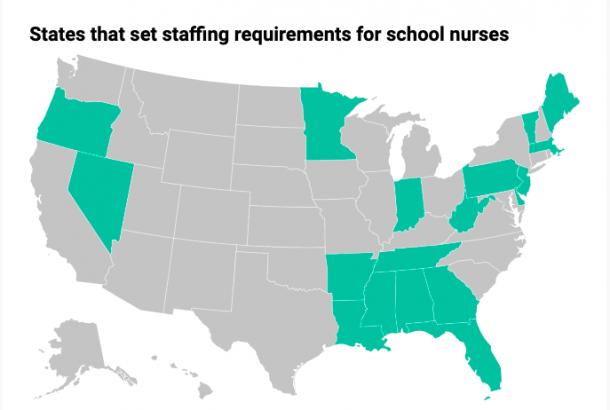

That’s the nurse-to-student ratio for K-12 schools in Pennsylvania — one of a handful of states to set staffing requirements in the law.

Karla Coffman, a nurse in the York Suburban School District, is about 250 students away from reaching that threshold as the certified school nurse for the high school and one of the district’s elementary schools.

With nearly 3,000 students enrolled across six buildings, York Suburban, about 40 minutes from Harrisburg, employs three certified nurses, three full-time health assistants, a floating health assistant, and another who provides care to one student within the district.

So far, meeting those responsibilities hasn’t been an issue, and a nurse having to travel from one facility to another hasn’t meant life or death in York Suburban. But student health needs have changed since the Pennsylvania General Assembly wrote staffing requirements into the Public School Code nearly 60 years ago.

Though once appropriate for K-12 schools, the requirements are now “unrealistic,” Coffman said.

“You can not use those same standards in our world today,” Sherri Taylor, a nurse at Red Lion Area Senior High School, also in York County, told the Capital-Star. “The only care for a student that was diabetic was to keep that child home because we didn’t have finger sticks. We didn’t have insulin pumps. We didn’t have continuous glucose monitoring systems. A child with cancer didn’t come to school; a child with severe asthma wouldn’t have come to school.”

Now, kids with chronic health conditions can attend in-person instruction in a traditional school setting, and nurses are the first line of care, Taylor said.

“We see that kid every day,” she said, adding that school staff likely interact with kids more than primary care providers or specialists. “We know the norm. We know when something’s wrong or when something’s off.”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that more than 40 percent of school-aged children in the United States have at least one chronic health condition — asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, obesity, and food allergies. Additionally, young people are experiencing the mental health effects tied to the COVID-19 pandemic after two years of mixed instruction and isolation.

Over the last two years, nurses — also dealing with the consequences of a nationwide staffing shortage — took on the role of a health department, helping districts develop health and safety plans for COVID-19, monitoring case counts, contact tracing, and sometimes covering multiple buildings. When schools reopened for in-person learning, they maintained their standard job duties as students demonstrated increased need during the health crisis.

School employees have taken on additional roles for years, resulting in workplace burnout and limited resources. Cuts to health professionals are not new. Over the years, districts have opted to have one nurse cover multiple buildings.

Data from the National School Nurse Association show that 35 percent of schools in the United States employ part-time school nurses, and 39 percent reported having full-time school nurses. Across the country, 25 percent of schools did not have a school nurse.

In Pennsylvania, state lawmakers have introduced bills to update the staff-to-student ratio. The proposals, which have never passed the Republican-controlled Legislature, would adhere to recommendations from the CDC, which calls for one nurse for 750 students. But with an ongoing staffing shortage, officials aren’t convinced that changing the ratio would help ease the burden on K-12 school staff.

“No school district in Pennsylvania should be talking about layoffs or limiting health, mental health, and disability resources,” state Rep. Dan Miller, D-Allegheny, who has introduced legislation updating staff-to-student ratios, told the Capital-Star. “If anything, we should be expanding those opportunities. Limiting those is an injustice to what we know to be a problem, and what was a problem before the pandemic has arguably gotten worse.”

A fascination turned reality

Motivated by a desire to help others, Coffman — a former child and youth services caseworker — decided to become a nurse after being “fascinated” with the profession while visiting her mother in the hospital.

Eventually, a substitute position turned into a full-time nursing job in the district where she lived, and her kids attended school.

But assumptions she made about the field were quickly debunked when she went back to school for her certification.

“I always assumed that there was a nurse in every single building. And when I signed up to be a substitute, I thought that I would be competing with tons of nurses within my community for substituting time,” she said. “That was absolutely not the case.”

Nearly 80 percent of Pennsylvania’s 500 K-12 school districts reported 1,997 full-time nurses during the 2016-17 academic year. Outlined in a 2018 Pennsylvania School Safety Task Force report, that’s an average ratio of one nurse for 809 students.

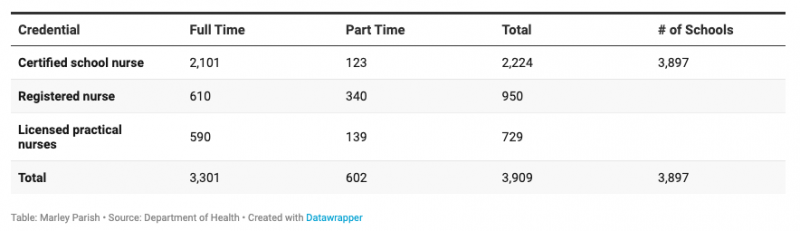

The Department of Health tracks school nurses and supplemental nurse staffing for public school districts, charter schools, cyber charter schools, and career and technology centers that seek reimbursement from the department. There is no existing mechanism to track school nursing staff at private schools, spokesperson Maggi Barton told the Capital-Star in an email.

Data representing 686 school entities statewide provided by the Health Department show 2,101 full-time certified school nurses, 610 registered nurses, and 590 licensed practical nurses. Roughly 315 out of the 500 public school districts in Pennsylvania have more than 1,500 students enrolled.

“What happens is that school nurse covers multiple buildings,” Pennsylvania State Education Association President Rich Askey said during a March interview. “And I’ve been there when I had a student have an asthma attack, and we’re all waiting for the school nurse to come from another building a few miles away.”

In 2013, a sixth-grade girl at a school in Philadelphia without a certified nurse on duty went home because of an asthma attack. She later died on her way to the hospital.

PSEA supports efforts to adjust the nurse-to-student ratio in Pennsylvania, including legislation from Miller to set requirements for counselors, psychologists, and social workers. Miller has also introduced legislation to set standards for counseling services in K-12 schools.

Taylor, who serves nearly 1,500 students at Red Lion Area Senior High School, is the only certified nurse — out of five — with one building districtwide. The other nurses have two facilities on their caseload, she said. The district also employs ten health room nurses, either LPNs or RNs, with full-time or part-time schedules.

Add staff members to the count, and Taylor and the health room nurse could be responsible for up to 2,000 people each day — “basically the size of a small town,” she said.

Click here to search the table

Certified nurses and supplemental staff undergo training. So if a student or employee has a medical emergency, such as a bee sting, school health professionals can respond as needed, even in cases where a nurse is traveling from another building, Taylor said.

“In our district, we’re fortunate. But that’s not the case in every district in Pennsylvania or every building in every district,” she said.

Taylor said there could be days when she’s absent and without a substitute to cover, leaving the health room nurse alone in the building, with the junior high school certified nurse roughly a half-mile away if there’s a “serious emergency.”

“But at the same time, that’s a huge responsibility,” Taylor added.

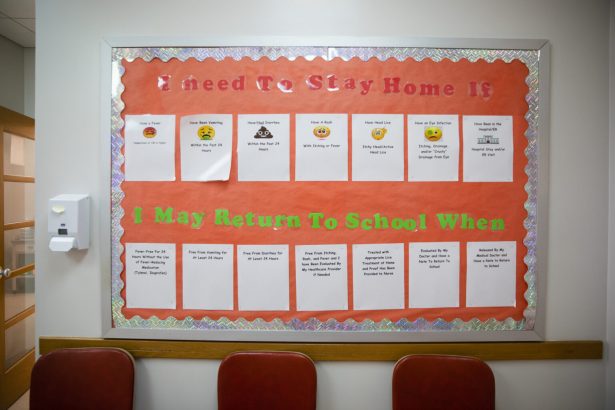

More than treating scrapes and bruises

If Coffman misses a day of school, especially if she knows she’ll be absent ahead of time, she makes every effort to find a substitute because “we don’t want to see any of our buildings go without a nurse.”

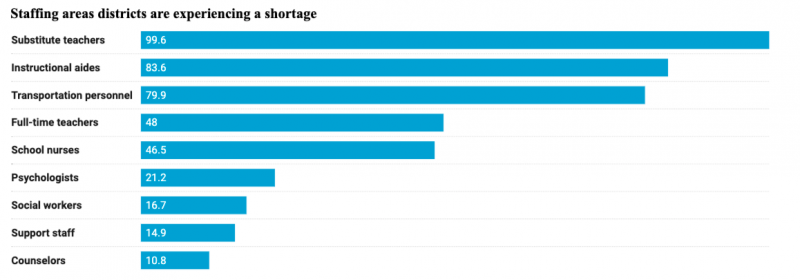

A 2022 State of Education report, developed by the Pennsylvania School Boards Association and the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators, stated that nearly every school district reported staffing shortages, with 46.5 percent of districts reporting a nursing shortage.

Sarabeth Abalos, a substitute school nurse and director of the BSN Program and the Health Professions Institute at Thiel College in Mercer County, told the Capital-Star that she makes about $12 an hour working in the Sharpsville Area School District in Mercer County.

Sharpsville, which has roughly 1,000 students enrolled, uses Precision HR Solutions, a Delaware County employment agency, to contract day-to-day staff.

“That has always been a hard sell for a registered nurse to go and work for $12 an hour,” Abalos said. “And you are assuming a tremendous amount of responsibility when you are the only medical professional in a building.”

If Abalos didn’t already have a full-time position at Thiel College and wanted to work as a substitute nurse every day, she could.

Abalos said nurses, specifically in smaller districts with one nurse per building, have difficulty balancing daily duties with mandated procedures, such as vision and hearing screenings.

“There are records to be kept, screenings to be done,” she said. “There’s so much paperwork that they have to maintain in addition to their actual nursing responsibilities, and I think there’s potential for so much good for society. But they simply don’t have the time to engage at that level.”

Before the pandemic, Taylor, joined by a school social worker and high school students, worked on a remediation program and campaign to combat vaping, targeting students at all levels. She also helps at a group home for teenage moms. Her typical daily job includes record-keeping, caring for students with chronic illnesses, and treating those in need with an education-based approach.

“Students will come in and say, ‘Oh, I have a headache.’ I’ll ask if they had anything to eat today. And they’ll say, ‘No, can I have ibuprofen?’ And I’ll tell them that it’s really not in your best interest to take ibuprofen because it can be upsetting to the stomach or an empty stomach,” Taylor said. “It’s those little snippets of what I’d call real-life education.”

Coffman recently obtained her CPR instructor certification, so she can train nurses and school staff members. She serves as the advisor for the Owning My Blackness Club, which was founded by a York Suburban graduate now attending York College. Coffman also oversees a local Hope Squad chapter, which works to address youth and teen suicide by empowering them when they experience social and emotional crises.

Taylor also incorporates lessons on resiliency into her daily interactions with students.

“The world is a different place for them,” she said. “And we’re at that point right now where they have to be taught how to bounce back, and that it’s OK to bounce back, and life is going to get better. It’s not always going to be down in the dumps.”

‘Cautiously optimistic’ about garnering bipartisan support

Outside of support from school administrators, colleagues, and loved ones, all three nurses said lawmakers should focus on legislation to increase funding for staffing recruitment and retention efforts, as well as adjusting the School Code to meet CDC recommendations.

Investing in school health services leads to fewer student absences, Coffman said. And with more staff and educational resources, districts will have more accurate medical records, increased immunization rates, fewer student pregnancies, and “just better health outcomes overall,” she added.

Miller, who has repeatedly introduced legislation to address school staffing ratios and health services, said he’s “cautiously optimistic” that colleagues from across the aisle will support his bills, currently before the House Education Committee. His hesitancy, however, stems from Democrats being in the minority party.

“We need people who echo those concerns on the floor of the House and in committees to find — if not my bills — find solutions to make learning more accessible and to support our teachers and other school professionals,” Miller said. “But when you give them ratios that are unworkable, you’re almost negating the value of having any of those support services in place at all.”

If Miller’s proposals survive the House and make it to the GOP-controlled Senate, they’ll likely face opposition from the majority.

Sen. Judy Ward, R-Blair, a former nurse, serves on the Senate Education and Health committees. In a statement to the Capital-Star, Ward said “now is not the time” to consider changing staffing ratio recommendations because they require funding and hiring people to fill newly required positions.

“Our health care workers are critical to serving the needs of others in our communities. But with the pain of a workforce crisis facing just about every employer right now, the introduction of mandated or increased mandated staffing requirements may not be best — certainly not attainable,” she said. “This is especially true for rural healthcare providers.”

Sen. Scott Martin, R-Lancaster, who chairs the Senate Education Committee, told the Capital-Star that school boards have a lot of power in Pennsylvania.

“There’s nothing in law that prevents them from hiring more nurses,” he said, adding that he hasn’t heard nurse-to-student staffing ratios raised as a concern among constituents. “There’s a lot of industries in Pennsylvania that are facing crucial shortages right now.”

Reflecting on the staffing crisis affecting industries statewide, Martin suggested that the state funding commissions could help address the crisis. He added that the Higher Education Funding Commission could analyze how to allocate money to address shortages and ensure those entering the workforce are hired for a “good-paying job” immediately, thus addressing multiple issues through targeted investments.

Gov. Tom Wolf, who staked his legacy on education and leaves office in January 2023, proposed $1.55 billion in new education funding as part of his final budget. Democrats have also called for increased allocations, so schools have the resources to recruit and retain staff and make decisions based on individual needs.

But when it comes to changing the nurse-to-student ratio, the administration said the staffing crisis “could result in additional staffing problems for schools,” Elizabeth Rementer, a spokesperson for Wolf, told the Capital-Star.

“Such a mandate also could force schools to direct resources to attaining the required ratio rather than to areas where the needs are more critical,” she said.

Pennsylvania Capital-Star is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Pennsylvania Capital-Star maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor John Micek for questions: [email protected]. Follow Pennsylvania Capital-Star on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)