Parents File Lawsuits to Halt School Face Mask Mandates as Districts Impose Health Rules to Slow Pandemic

By Mark Keierleber | September 14, 2020

Grace Warniment vowed to never put a face mask on her elementary-age sons. Even as public health officials recommend that students cover their faces on campus to slow the pandemic’s havoc, the Florida mother insists that cloth face coverings are disgusting — and could put her kids at risk.

“Why would I cover my children’s face when they’re healthy?” she asked. “You’re only going to lower their immune system. The masks are what are hurting people.”

So when her school district in Hillsborough County reopened with a requirement that students wear face coverings on campus, Warniment teamed up with parents she met in a Moms Against Mask Mandates Facebook group and sued.

Similar lawsuits have cropped up across the country, from Tennessee to Connecticut, as campuses reopen for in-person learning with a slew of new public health rules after months of remote instruction. As officials respond to the public health emergency, the lawsuits highlight fierce pushback among some citizens who argue that the mask requirements amount to government overreach. In classrooms and beyond, face masks have become a symbol of political strife, and school policies on them vary across the country. Three-quarters of Americans, including half of Republicans, believe that face masks should be required in public, according to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey from July. No federal requirements on masks exist, and President Donald Trump himself flouted a state mask mandate at a recent campaign event.

But beyond the ideological overtures — some of the plaintiffs also oppose vaccines — the pandemic-driven lawsuits also highlight the logistical challenges of requiring students to wear masks over the course of a school day, especially with young children and those with special needs.

Warniment’s younger son, 6-year-old Brady, was recently diagnosed with autism and has sensory sensitivities that make wearing a mask a challenge.

“Certain types of fabrics he can’t wear,” Warniment said, because they make him feel itchy and claustrophobic. “We’re not going to put a mask on Brady because he will rip that thing off his face. He will rip it right off. It doesn’t have to do with me teaching him that masks are useless. He won’t wear it.”

Pooling their resources, Warniment and the other parents hired Patrick Leduc, a Tampa-based attorney who said he became known locally as “Mr. Face Mask Guy” for fighting public health orders. In an effort to overturn the district’s face-mask mandate, the lawsuit lobs an array of allegations, including claims that masks are ineffective, that children are unlikely to spread the virus and that students are being denied access to a free public education required under the state constitution. The rules were put into place without adequate public input, the lawsuit alleges, and interfere with parents’ rights to determine medical decisions for their children.

Under the district rule, students who decline to wear masks must attend classes virtually — an arrangement that’s discriminatory and is “detrimental to their health” because of extended exposure to technology, he said.

“The purpose of the lawsuit is to empower parents to make these decisions,” Leduc said. “I believe that a parent knows their child better than the school board knows their child.”

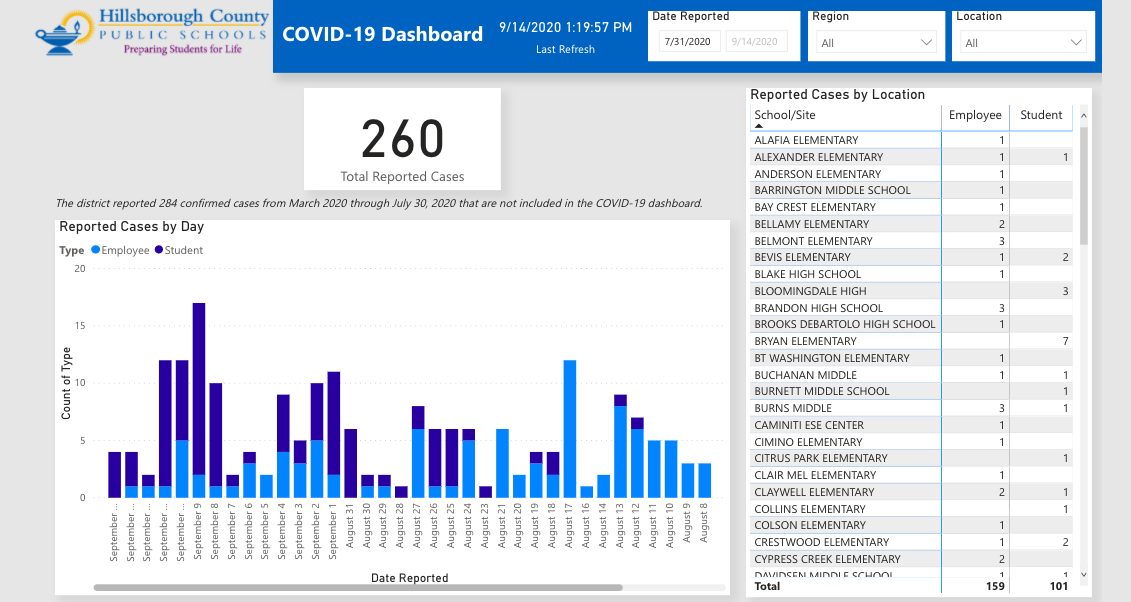

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, has pushed schools to reopen for in-person learning, but state guidelines don’t require students to wear masks at school and many districts have opted not to require them. In the past month, the state has seen a 34 percent spike in infections among children, though it remains unclear whether the surge is tied to schools, according to The Washington Post. Citing privacy concerns, the DeSantis administration has ordered some districts not to release certain virus data. In Hillsborough County, there have been more than 180 reported cases among students and educators between July 31 and last week, according to a district dashboard. The district serves roughly 220,000 students.

Public health officials recommend a more proactive approach. With “rare exception,” children ages 2 and older should wear cloth masks at school when social distancing is not possible, according to recent interim guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Recent guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention makes similar recommendations. Masks provide “a simple barrier to help prevent respiratory droplets from traveling into the air and onto other people when the person wearing the mask coughs, sneezes, talks or raises their voice,” according to the CDC. However, the agency notes that masks should not be placed on children who have trouble breathing or are unable to remove it without help.

Districts without mask mandates have also come under fierce criticism. After a Wisconsin district returned to in-person learning without a mask requirement, officials reversed course when students launched a petition accusing leaders of hypocrisy for enforcing a dress code.

Nathaniel Beers, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., said the virus is generally milder among young children than with adults and that they’re less likely to spread it to others. However, kids are far from immune, he said, and face masks are effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19, particularly from asymptomatic carriers. If campuses reopen for in-person learning, he said, mask rules are important to keep students and educators safe. Meanwhile, a growing body of research suggests that children are more susceptible to catching and transmitting the virus than previously understood.

“While I understand people’s desire to have individual rights, this is a public health emergency and we all need to be doing our part to ensure that we are reducing the spread of disease and decreasing the number of individuals in our community who will be severely impacted by COVID or die from COVID,” said Beers, who helped craft the AAP’s guidance on masks in schools. “The best way for us to do that — and the simplest way for us to do that — is to ensure adequate use of face coverings.”

Yet in an interview with The 74, Leduc questioned public health officials’ expertise, comparing their guidance to the government’s response to the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, arguing that he spent years of his life “in a desert” while serving in the Army “because of idiots who couldn’t get it right.” Less than two years after the 9/11 attacks, the United States invaded Iraq based on intelligence reports, later proven unfounded, that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction.

“Now we’re in 2020 and we can look back to 2001 and say, ‘You know, did we overreact here?’” he said. “When government declares an emergency, they have all of this power and the only thing that can really be a bulwark against that is both the state and the federal constitution. COVID-19 should not make the rule of law a victim.”

‘Separate and unequal’

When schools reopened in Hillsborough County last month, students had two options: Don a mask in class or receive instruction virtually. To Warniment, neither option was sufficient.

Though the school district said Brady could have an exemption from the mask rule because of his disability, his mother feared that his classmates would bully him for attending school with his face uncovered. So instead, she used Florida’s voucher program for children with disabilities and enrolled him in a private school. He now attends first grade at a school with 10 children per class. Masks are optional.

Warniment’s oldest son, 8-year-old Cole, currently attends third grade virtually, an arrangement that she argues subjects him to a “separate and unequal education,” citing the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that struck down racial segregation in public schools.

“Instead of being segregated by color, now we’re segregated because we’re not wearing a mask,” said Warniment, who currently studies pre-law online at Liberty University, the evangelical Christian college founded by the Rev. Jerry Falwell Sr. “Some people have a family member at home with an underlying condition — we completely understand that. But that group of people is a lot smaller than the healthy group of people, so why are we being held hostage for those who are the vulnerable?”

In a statement, Hillsborough County Public Schools spokeswoman Tanya Arja said the district mask policy is based on guidance from the CDC and the local health department. She noted that exemptions are available for children with medical, physical or psychological conditions.

“The experts agree that face coverings are one of the most effective means for preventing the spread of COVID-19,” Arja said in the statement. “We are sensitive to the unique challenges with requiring face coverings in a school setting, but we believe it is one of the most important strategies we have to provide an additional layer of protection for everyone on our campuses.”

A similar legal fight is playing out in Connecticut, where state officials imposed a mask mandate as a condition for school districts to resume in-person learning this fall. Represented by two Republican state lawmakers, the parents and the legal advocacy group CT Freedom Alliance argue that the rule violates the state constitution. The lawsuit charges that the rule was created without providing an opportunity for public comment and denies children access to a public education afforded under the state constitution. State officials imposed the requirement with “no scientific foundation and no legislative foundation,” argued Alliance co-founder Brian Festa.

“Even during a public health emergency, you still have to notify the legislature and you have to go through a regulatory process,” he said. Parents have “been told, ‘You’re doing this whether you like it or not, and if you’re not, your kid is going to be shut out of school,’ basically expelled from school,” he said. Similar to the policy in Hillsborough County, the Connecticut rule says children must attend classes virtually if they decline to wear a mask. In effect, he said, schools are discriminating against children because “they are being physically removed from the schools. The doors of the schools are locked to them.”

“By seeking to eliminate protections for students in school, this lawsuit puts children and educators at risk and makes us less safe. Plaintiffs do not have a constitutional right to endanger their own children and put their classmates at risk.” —Willam Tong, Connecticut attorney general

William Tong, Connecticut’s attorney general, pledged to defend his state’s mask mandate and argued that the lawsuit is politically motivated and “potentially dangerous.”

“By seeking to eliminate protections for students in school, this lawsuit puts children and educators at risk and makes us less safe,” Tong said in a statement. “Plaintiffs do not have a constitutional right to endanger their own children and put their classmates at risk.”

Wide range of complicating factors

Though the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children wear masks in school with few exceptions — and that they’re safe for “the vast majority of children with underlying health conditions” — attorney Francisco Negron offered a less prescriptive stance.

Negron, the chief legal officer at the National School Boards Association, said that school leaders should work in concert with public health officials to determine whether local infection rates necessitate mask mandates.

“It’s clear that school districts have an obligation to keep children safe, not unlike existing state requirements for vaccinations or other kinds of safety measures,” he said. “The law is strongly on the side of school districts, provided that school districts have made their decisions about mask wearing grounded in the appropriate recommendations of public health officials.”

However, he added that educators may need to make modifications for some children with disabilities, noting that such accommodations are required under federal special education law.

“If you have a child who is not reacting well to a mask, it’s hard to have them on task and learning and so it’s not just a question of comfort,” he said. In response, educators should craft workarounds that are individualized to fit students’ unique needs. “They might not tolerate a face mask, but they might tolerate a face screen. Some might not tolerate either, but they might tolerate social distancing. Some might not tolerate any of that but could do well in a distance-learning environment.”

But making strides with children who struggle to wear masks is within the realm of possibilities, Beers said. Many of his patients have significant sensory issues, he said, but several strategies make the challenges easier to overcome. For example, a mask with a friendly design such as a Star Wars or dinosaur theme could be more appealing to children, he said. Despite a wide range of complicating factors — from children with facial abnormalities to those with anxiety — he said practice and parental encouragement can go a long way.

But even beyond the practical hurdles, districts face significant ideological challenges that aren’t likely to go away anytime soon. In fact, the issue could become more fraught once a coronavirus vaccine becomes available.

Festa of the CT Freedom Alliance has previously fought Connecticut lawmakers’ efforts to eliminate a religious exemption to mandated vaccines. He vowed to “vigorously oppose” any policies that require students to receive the coronavirus vaccine.

Warniment, who believes Brady developed autism after receiving the measles vaccine, agrees. Though there’s no link between vaccines and autism, according to the CDC, she doesn’t plan to give her children the coronavirus vaccine once it becomes available.

“Most of us parents that are against vaccines are against the masks,” she said. “They think they can just rush a vaccine and we’re going to openly let it go into our kids’ bodies? Nope.”

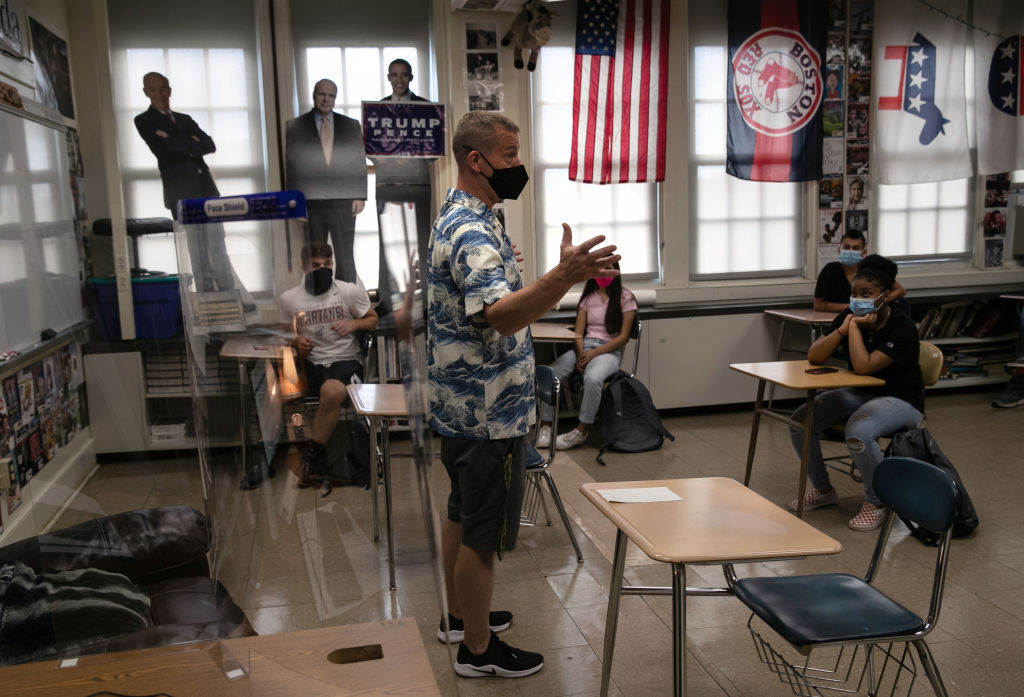

Lead Image: First day of in-person learning at Perry Elementary School in Shoemakersville, Pennsylvania. (Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter