Parents Expected to Opt Children Out of Spring Testing in Large Numbers, Especially in Places Where Schools Haven’t Reopened

The U.S. Department of Education might expect standardized assessments this year, but state and district leaders are predicting a lot of empty seats. While parents generally want more data on their children’s performance, many say they’re unwilling to send them back to school during the pandemic just to take a test.

In Florida, more than 7,000 parents have signed petitions asking for state assessments to be cancelled. Others in Florida’s Duval County want an option to take the test virtually. And in the District of Columbia, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education will “seek to suspend” an annual assessment following requests from parents.

Many education groups last week commended the department for not canceling assessments outright and instead offering broad flexibility for when and how they can be given. They argue that comparable data across districts and by students’ race and poverty level is needed to measure the impact of the pandemic on children’s learning. Even with that leeway, however, some state and district leaders continue to speak out against the department’s decision, saying that it disregards the ongoing upheaval caused by school closures

On Thursday, New York City schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, who later announced he is stepping down, sent shock waves by suggesting parents in the nation’s largest school district exercise their right to opt out of assessments if they’re opposed to their children taking them.

Outgoing New York City schools Chancellor Richard Carranza discusses assessments for this year:

In addition, lawmakers in Texas have asked Gov. Greg Abbott to create a formal process for parents to opt out.

“We still do not feel comfortable, as Black and brown parents, to send our children to an in-school environment,” said Meenal McNary, who has three children in the Round Rock Independent School District, north of Austin, Texas. “Assessing students during this time only adds the trauma that they may be experiencing.”

Federal law requires states to annually test “not less than 95 percent of all students” in reading and math, as well as 95 percent of low-income students, English learners, students with disabilities and those in major racial and ethnic groups. Testing almost all students provides more accurate results, but the department last week noted that states could request a waiver from that requirement.

The law requires districts with a policy in place to let parents know they can opt their children out of annual assessments, if they ask. In a normal year, if more than 5 percent of students opt out, those additional students would be considered not proficient in overall results, which can lower a school’s rating on state report cards.

Whether or not parents officially opt out, some district leaders expect little or no participation.

“I do not know how I could possibly compel 13,700 students who are learning from home to come into a school building for a test when I cannot get them to come in to learn,” said Tony Sanders, superintendent of School District U-46, near Chicago.

Prior to last week’s federal testing announcement, he wrote a letter to the department, joined by almost 700 other Illinois superintendents, asking that assessments be waived this year.

And in Georgia, where state Superintendent Richard Woods came out early last fall requesting a waiver from testing for a second year, state education department spokeswoman Meghan Frick said, “We certainly expect that some parents who have opted for virtual learning, specifically if they’ve done so because their child or a member of the household is high-risk, will choose not to have their student enter a school building to take the test.”

The California Department of Education has asked for the maximum flexibility from the department, including a waiver from any penalties if less than 95 percent of students participate in assessments. New Mexico has also requested a waiver from that requirement and will instead test a sample of students.

Parents split on testing

Polls show that parents are split on the issue of assessments. New results from the National PTA and Learning Heroes, a nonprofit that advocates for parents’ access to data, shows that 52 percent support testing this spring. The rate climbed to 60 percent when parents were told that the stakes would likely be lower. For example, the results will not be used to rate schools or determine students’ promotion to the next grade.

In addition, new data released Monday from the National Parents Union, a network of parent advocacy groups, shows about “half of parents consistently support assessments as a means to determining what kids need and where there might be challenges,” said Keri Rodrigues, president of the organization.

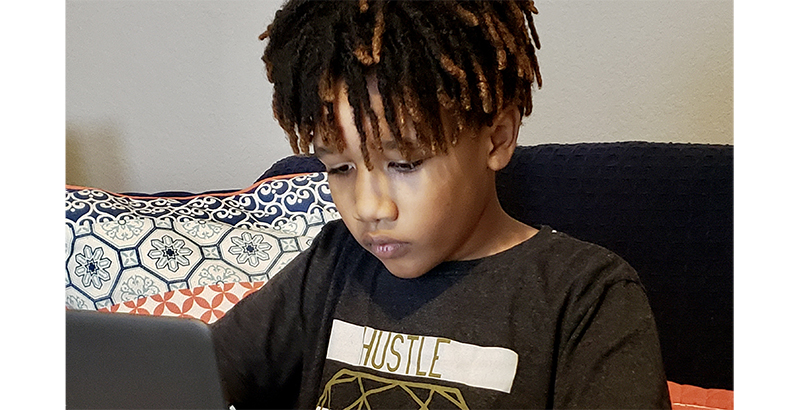

Some parents say they have gleaned some of that insight from observing their children’s remote learning and don’t feel assessments would tell them anything they don’t already know. Yolanda Miller, another Texas parent, brought her 10-year-old son Therren into her home office so she could observe him in remote classes and help if needed. She noticed that he gets confused about the teacher’s expectations. Her 13-year-old daughter Madison, however, is doing well in distance learning.

“I feel that students are not receiving quality lessons during these times and teachers are trying to stay afloat the best they can,” said Miller, whose children are in the Pflugerville Independent School District, also in the Austin area. “This is not the time to assess students’ growth and learning via the [state test]. It’s only going to reflect what parents and teachers already know. Everyone is struggling — students and teachers. Look at the grade book.”

Some parents are seeking expertise on how to excuse their children from assessments. Bob Schaeffer, the interim executive director of FairTest: National Center for Fair & Open Testing, said website traffic to the organization’s opt-out guide is more than seven times higher than it was at this point last year. He said the Biden administration “severely underestimated” reactions by parents and educators to the announcement that assessments would go forward.

‘We need to know how to do this’

Parental views on the matter tend to hinge a lot on the extent to which students have already returned to the classroom. Scott Marion, executive director of the New Hampshire-based Center for Assessment, said he expects opt-outs to be “huge in states that are engaged in largely remote learning if they ask kids to come into buildings to test.”

According to one tracker, almost 28 percent of students are still attending virtual-only schools, with the western states and Maryland least likely to have students back in school.

But Paige Kowalski, executive vice president of the Data Quality Campaign, said if parents do opt out, it will be difficult to draw assumptions about why. “There is a critical difference between a parent who wants to make a statement about policy and a parent with three small children at home sharing one device on weak broadband,” she said.

Concerns remain that allowing virtual assessments would taint the results because of the possibility of cheating. But Kowalski said it’s time to solve that dilemma.

“We can’t just say remote assessments don’t work for everybody in this country,” she said. “I don’t think this is our last time to do school at home. We need to know how to do this.”

Other experts see current movements to opt out as part of a larger trend.

“There’s a broader anti-test backlash that’s been brewing for many years and that has accelerated under the pandemic and in response to recent racial reckonings,” said Morgan Polikoff, an educator professor at the University of Southern California. “I don’t see that slowing down just because schools are opening up.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)