Educator. Mentor. Translator. How One Man Aided Immigrant Families Through COVID

Ted Pedro has done it all to help his neighbors in the foothills of Appalachia build community and thrive during the pandemic

By Kevin Mahnken | May 30, 2022This is one article in a series produced in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project, spotlighting educators, mentors and local leaders who see community as the key to student success, especially during the turbulence of the pandemic. See all our profiles.

“Hello?”

“Hello, good morning. I’m looking for Moises’s parents?”

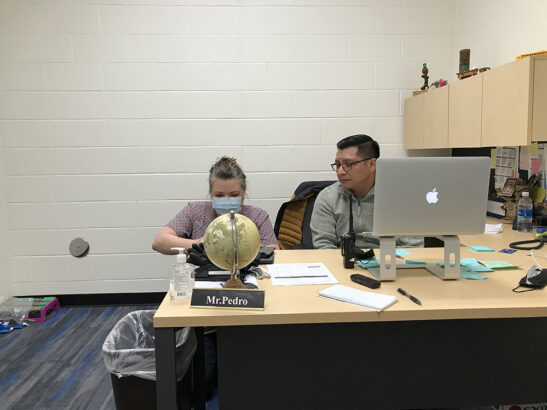

In a windowless office at Mountain View Elementary School in Morganton, North Carolina, Ted Pedro settled in for another call he’d rather not be making. It was a few minutes past 9 a.m. on a Thursday in early January, and already, he’d dialed three Spanish-speaking families to break the news of their children’s possible exposure to COVID-19.

Pedro is one of a handful of “parent educators” employed by Burke County Public Schools, a district serving about 12,000 students in the state’s Appalachian foothills. In that capacity, he has worked for four years as part-interpreter, part-social worker to Mountain View’s Hispanic families, many of whom traveled thousands of miles to live and work here. His chief focus is helping them adjust to the rhythms of life in western North Carolina — a transition he understands well, having immigrated three decades ago from rural Guatemala.

The present conversation, like untold hundreds that preceded it, developed into a kind of ritual over the last two years. Moises’s mother had kept him home that morning, along with her two daughters in middle and high school, after they all tested positive for the virus the day before. Flanked by school nurse Tonya Kiser, Pedro translated a familiar sequence of questions over speaker phone and extracted the necessary details: When did Moises’s older sister begin experiencing symptoms? (Tuesday.) Was the boy symptomatic? (No.) Had he been vaccinated? (Yes, both doses.)

It was only a few days after the return from Christmas break, and the school environment was easily as hectic as Pedro or Kiser had seen over the course of the pandemic. Illness started trending upward a month earlier, with the holidays undoubtedly hastening its spread. Within a week, North Carolina would ride the Omicron wave to a record number of COVID hospitalizations, and at Mountain View, the dawning emergency was scrambling routines and responsibilities daily. Every hour brought new exposure notifications, more children isolated in the building’s care rooms, and impromptu meetings with parents to settle on dates for further testing and possible return to the classroom.

Pedro’s work in 2022 is a late-COVID variation of the services he offered before the pandemic changed life in Burke County and the rest of the world outside. Over the past two years, he has spoken in three languages to families living on the margins, shepherding them through the technical follies of virtual instruction and the social dislocation of life during a public health emergency. His personal awareness of the struggles they confront, from finding a local church to coping with the occasional winter cold snap, has made him both a friendly ambassador for the district and an example to follow in a rapidly diversifying Morganton.

As the call carried on, the pair offered more assurances to Moises’s mother that he could log on for virtual learning and come back to school the following week. New state guidance recommended a much shorter isolation period than was previously permitted. When Kiser ran out of space on an envelope she was using to tabulate the date of the boy’s return — five days after a positive test, provided he didn’t develop symptoms in the meantime — Pedro reflexively handed her a Post-It note and unwrapped a peppermint; the constant stream of calls seemed to exact a toll on his voice.

Hanging up, he turned to a stack of self-directed notes and reminders piled in front of his keyboard. Two parents he’d contacted earlier were waiting outside to collect their quarantined children and fill out consent forms to receive free COVID tests on campus. Often as not, he said, kids were simply stricken with strep throat or ear infections. But their families were grateful to direct their questions to a fellow Spanish speaker.

“I make sure the parents know what’s going on so they’re not in the dark,” he said “Just imagine coming in, and there’s nobody that speaks your language. With me being here, it makes the parents feel at ease.”

Christie McMahon, the third-year principal at Mountain View, analogized the difficulties facing local Hispanic parents to the “intimidating” thought of having to raise her own children in a country like France. The ties between families and the school run substantially through Pedro, whose affection for the — he refers to it sometimes as “our little town of Morganton” — borders on the evangelical.

“Ted has lived through a lot of these parents’ experiences,” McMahon said. “He knows what they’re facing, and because they go to him and feel comfortable with him, he’s become a window into this world whose challenges we might not have been aware of.”

Harrowing trek

Long before the pandemic, too many in the local Hispanic community found themselves disconnected.

The city of roughly 17,000, located about 60 miles east of Asheville, has seen its Hispanic population steadily expand in the last few decades as families migrated from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. Some are drawn to the furniture factories in nearby Lenoir, but a sizable number opt for jobs at Case Farms, the sprawling poultry processor off Route 70 in Morganton. Working conditions at the facility have drawn scrutiny in recent years, with some employees reportedly wearing adult diapers to compensate for a lack of bathroom breaks. When the plant saw a COVID outbreak in the spring of 2020, Kiser, who has worked in the school system for over a decade, said it was hard to find care for some of the students she and Pedro worked with — especially those whose families had entered the country illegally.

“It’s very humbling on a personal level to think about some of the stories they won’t tell you,” Kiser said. “Thinking about how they got to be in Morganton, North Carolina, will put you on your knees and make you ashamed for what you have.”

Pedro, who started as a volunteer interpreter in his own children’s classrooms, soon understood the need for outreach to parents with little command of English. Some had never made it past the third or fourth grade in their country of origin, but all shared the desire for the next generation “to be better than where they’re coming out from.”

“This is one of the things we’ve been pushing since I came here: Education will make your life better,” Pedro said. “Maybe not now, but in about 10, 12 years, you’ll be able to speak the language, you’ll be able to make moves in your life that you’d never be able to do in your own country.”

Pedro (christened Teofilo, after his grandfather, though the name was later Americanized to Ted) was born in a heavily indigenous region called Huehuetenango on the southern border of Mexico. When he was three, his parents left him and his infant brother in the care of their grandparents and fled to California to escape the violence of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war; his father returned after a few years and brought them on the same harrowing trek, allowing the family to be reunited in Los Angeles. At the time of his arrival, he and his brother could speak only Q’anjob’al, the Mayan dialect widely used in their hometown.

They lived in an eight-story apartment complex, the biggest structure Pedro had ever seen at the time. Because of overcrowding at nearby buildings, his father enrolled him in a newly started school in the Pacific Palisades. The morning commute took almost 90 minutes in L.A. traffic, but Pedro remembers the long bus ride as “a blessing”; as the music of Sade and Luther Vandross filtered through the speakers, he and his classmates would get a glimpse of the Santa Monica beaches where camera crews were filming Baywatch.

In the late ‘90s, the family decamped for Morganton, where Pedro’s father found part-time work in the furniture trade and eventually established his own trucking business. One of a handful of Hispanic students at the time, Pedro made a niche for himself on the soccer team and in junior ROTC. After weighing a decision to enlist, he instead married his sweetheart and found himself contented to raise his young family where he’d grown up.

Before signing on as a parent educator, Pedro worked for several years translating in federal court proceedings, where his knowledge of Q’anjob’al gave him a rare and highly lucrative skill. But the work demanded constant travel on quick turnarounds, and he missed the opportunity to build lasting relationships with the people who depended on him. At the same time, he took note of the Hispanic parents around him, including parents of his childrens’ classmates, who were navigating the same rocky path his own family had followed nearly 30 years before.

It was seeing those first-generation immigrants floundering “without somebody to say, ‘This is where you need to go, these are the classes you need to take,’” that moved Pedro first to pitch in as a parent chaperone, then apply for a job at the newly opened Mountain View Elementary in 2018.

“From riding those waves by myself, [watching] my parents ride their own waves by themselves, I knew how to support my kids as a parent,” he said. “But I also saw parents not having that support, and that’s when I got myself into it: volunteering on field trips, or if a teacher needed an interpreter. And when this job came open, I knew it was the opportunity I’d been looking for for years to help out.”

Throughout four years in the school system, Pedro noticed a steady stream of Hispanic arrivals — seven or eight new families each month, many coming from other states or outside the country — that only quickened with the recent refugee flood from Central America. Mountain View’s student body of about 700 is somewhere between 40 and 50 percent Spanish-speaking, and the school operates a growing dual-language immersion program to accommodate them.

Pedro’s work for the district occasionally extends beyond his own school. After wrapping up morning calls, Pedro greeted a Guatemalan father and son who needed help enrolling in another elementary school in the district. The pair had recently moved from Alabama, and neither the father nor his 10-year-old son, Baltazar, spoke English. When they arrived, Pedro directed them to a conference room around the corner from his office.

He spent the next 40 minutes guiding the father through a raft of candy-colored forms on student health, residence, emergency contacts, learning needs, and free lunch eligibility. In the absence of a Spanish-language interpreter, the process could have easily taken the better part of a day.

Between explaining each of the documents, Pedro quizzed his countrymen on their background. By chance, it emerged that they had also immigrated from San Mateo, a neighboring town in his home region of Huehuetenango. Pedro jokingly inquired about the local delicacy las shecas — a sweet bread that he confessed to ordering “by the pile” — and advised the father to continue speaking to his son in his Mayan dialect of Chuj. Even as he labored to learn English, the linguistic versatility would be valuable, he argued.

“He should never forget his dialect because when he’s older, he’ll know Spanish, English and your dialect — trilingual. Tell him to speak it all the time. I teach my children at home because nowadays, it’s very important.”

After showing the pair out, Pedro stationed himself briefly at the school’s front door, with a view of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance. An enthusiastic outdoorsman, he said the area’s wealth of lakes, rivers and mountains reminded him of his home country.

“It’s peaceful, it’s quiet,” he later explained. “Within the Hispanic community, a lot of the reason people come here is because of that. We could go up and live in Raleigh, Charlotte, Asheville, but I love it here.”

Morning rounds

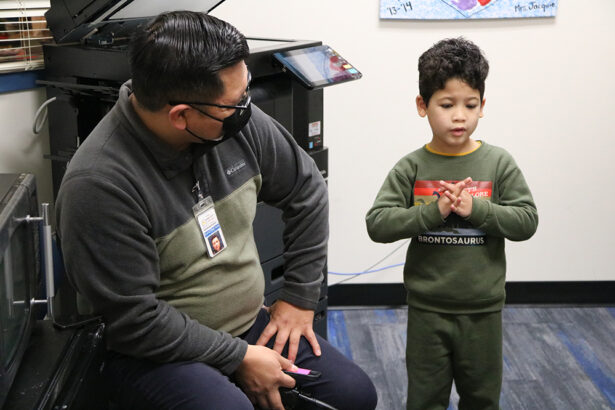

Belatedly, Pedro started the afternoon by embarking on what he calls his “rounds” — quick visits with Hispanic students who benefit from extra attention and guidance. After a few turns down the school’s cavernous hallways, he knocked on the door of a dual-language classroom and pulled aside Kilian, a kindergartner who came to Mountain View the previous September.

A lilting, talkative boy from Puerto Rico, Kilian speaks beautiful Spanish but occasionally loses his composure in class. That morning, he’d grown impatient while completing an assignment and threw a kindergarten-sized tantrum.

Pedro bent to tighten the five-year-old’s shoelaces, his voice quieting almost to a whisper as he drew out answers. Kilian had gotten frustrated when realizing he wouldn’t have time to finish writing an answer, so he threw his pencil to the ground.

“But what’s the best way to work with the pencil?” Pedro asked. “What could have been done better?”

“Write and put it on the desk when I finish.”

“And what should you not have done?”

“…I shouldn’t have thrown the pencil.”

After a few minutes, Pedro gently reminded Kilian to calm himself when he gets upset, leading him in deep breathing exercises before excusing him to return to class. In a later conversation, he reflected that such intimate encounters with children and parents, either inside or outside of school, were the best part of the job.

“When you go out to Walmart or to the grocery store, parents see you and say, ‘Thank you. You see that you’re doing something in the community to bring them together — you give yourself to this job, and it’s like seeing the roots growing,” he said. “The satisfaction from that, I wouldn’t call it a job. It’s a gift God gave me.”

Those bonds were stretched to the limit over the last two years, when Burke County schools first closed for the end of the 2020-21 school year, then reopened on a hybrid basis until a year after the pandemic began. The herky-jerky transition between in-person learning and Zoom classes was daunting enough for heavily networked, English-speaking families; for immigrants, the challenge was at times insurmountable.

The crunch was especially tight in the fall of 2020, when the district relied heavily on virtual teaching software like Lexia and DreamBox to reach students at home. Mountain View staff rolled out wireless hotspots and prepaid data cards — sometimes passing them through windows to parents infected with COVID. Some nights, Pedro stayed on the phone until 10:00 at night with parents attempting to fix internet issues; the next morning, he would provide personal tutorials on how to access lesson plans online.

Always broadly sketched, the role of parent educator evolved as the pandemic threw up new roadblocks. For a stretch last fall, Pedro filled in for absent bus drivers, setting out before 7:00 each morning to complete two routes of student pick-ups. The experience brought him back to his own days riding out to school in Los Angeles.

The commitment he showed, said nurse Tonya Kiser, was reflective of the web of connections he’s formed with families who have few others to rely on.

“Ted starts building that relationship with these families, and…that builds and builds and builds. …It wouldn’t be the same without him.”

Principal McMahon echoed those sentiments, pointing to the school’s efforts to help newly arrived immigrants navigate a tortuous health care market. Before and during the pandemic, Pedro and Kiser have worked to connect families with community resources to pay for eyeglasses and dental care.

“If you’re undocumented, and your kids are sick, where do you go?” McMahon wondered aloud. “Ted works closely with families who might be hesitant to take a child to an urgent care or an emergency room because they don’t have insurance. And not only is he helping the families, he’s educating the people around him so that we’re also better and more attuned to those things.”

Building relationships

The next day at Mountain View was markedly quieter. With most of the week’s exposures already flagged and children sent home, winter Fridays tended toward calm.

Still, there were appointments to keep. Earlier in the week, a father had called to report that his daughter was sick and would need a COVID test. Arriving late in the morning, he brought eight-year-old Shenny to the front of the building, where Pedro met them with a nurse’s assistant. On the playground across the drop-off lane, a gym class played a desultory game of soccer in the sunlit chill.

The process moved along quickly. Pedro presented the father with a Spanish-language consent form as the nurse straightened her face shield. After a few uncomfortable-looking moments, the test was done; if the results came back negative, Shenny could come back Monday.

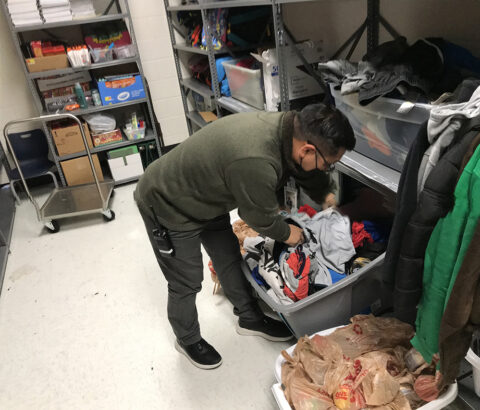

But as the pair turned back down the road, Pedro urged them instead to step into the vestibule. Frowning at the cold, he said he would bring Shenny some warmer clothes to wear over her pink jacket.

As they waited, he power-walked down the hallway to a storage room around the corner. Inside were overflowing shelves of toys and school supplies provided by local volunteers and church groups . Bags of snacks were kept in case families needed help keeping their children fed over the weekend, and a few racks held hoodies and jackets. Ted held up a tiny black coat to judge its size and discarded a few accessories before settling on a hat and gloves that looked like they would match.

“Let’s make it look good for her,” he muttered. “My daughter has been teaching me about fashion.”

Shenny smiled warmly while zipping herself up, then headed home with her father.

Outside, it was the brightest part of the day, the sun washing the Blue Ridge with yellow light. Under normal circumstances, he’d wait a few moments to admire the view, but just then, his phone buzzed with a new message.

The 74’s Marianna McMurdock provided Spanish translation assistance for this article.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to both the Weave Project and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter