Paramount Schools Succeed With Goats, Art And ‘Boring’ Looking Classes

Data and hard work, not just “Dead Poets Society” lectures, let Indianapolis charter schools reach challenged students, launch expansion across state.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It might be the goats living next to the schools’ playgrounds that make the Paramount charter schools some of the best in Indianapolis — or the cheese made from the goats’ milk.

It could be the carpets on all the floors.

Or even the framed prints hung on the schools’ walls of fine art from around the world.

The Paramount Schools of Excellence have a lot of “bells and whistles,” as one parent put it, that make them look and feel different from other elementary and middle schools.

Few schools have miniature farms out back, after all.

But observers and school leaders say more fundamental differences have made the network of schools — which will grow to six schools by fall — a fast-growing and top performer in the city.

All that coming from a single school started in 2010 that was warned that its D and F grades could shut it down. That school, now known as Paramount Brookside, has since received nine straight A ratings before the pandemic halted Indiana’s letter grades for schools. The U.S. Department of Education named that K-8 school a national Blue Ribbon school in 2018. Parents now drive their kids there every day from half an hour away.

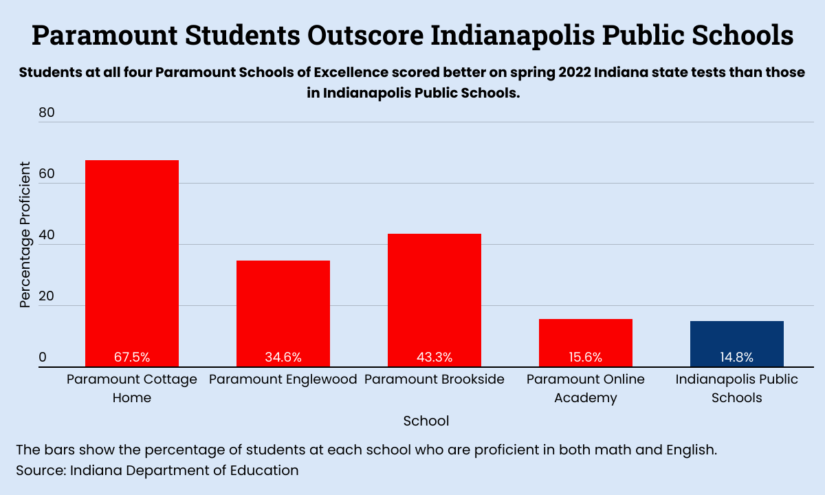

Paramount now has another elementary school and another middle school in the city, whose proficiency rates all far exceed those of the Indianapolis Public Schools by a wide margin. It added an online school and just opened new schools Aug. 1 in two other Indiana cities, Lafayette and South Bend. Paramount is also creating an innovative new all-girls STEM school in partnership with the Girl Scouts to open in 2024.

“There’s a culture, there’s a vibe, there’s a climate that is palpable in each of the sites,” said Danielle Shockey, CEO of the Girl Scouts of Central Indiana, who sought Paramount as a partner in the new school. “They all have this feeling of just calm, but yet exciting reverence to the opportunity to learn. That’s the foundation to what leads to the strong academic outcomes.”

Shockey, a former teacher and former deputy state superintendent, said Paramount’s academic results, teacher training program and ability to replicate its success at multiple schools drew her.

Tommy Reddicks, the founding CEO of the schools, credits more nuts and bolts reasons for success than the flashy trappings of goats, cheese, and paintings.

The biggest factor: Rejecting what Reddicks calls the “Dead Poets Society” approach of many schools who rely on inspiring lectures by passionate teachers like those portrayed in the Oscar-winning movie.

“You see in movies all the time, the teacher who gives the 45 minute amazing speech that really inspires the students,” Reddicks said. “Then, when the bell rings, as the kids are running out, teachers are like, ‘Make sure to get your homework done on chapter four.’ That model is like a poison pill for urban education.”

He added: “I’ve done school tours, where the principal says ‘This is our best teacher’ and you see them talking for 30 minutes. And it’s really cool what they’re showing and demonstrating. But there’s no student work happening. There’s no student interaction happening.”

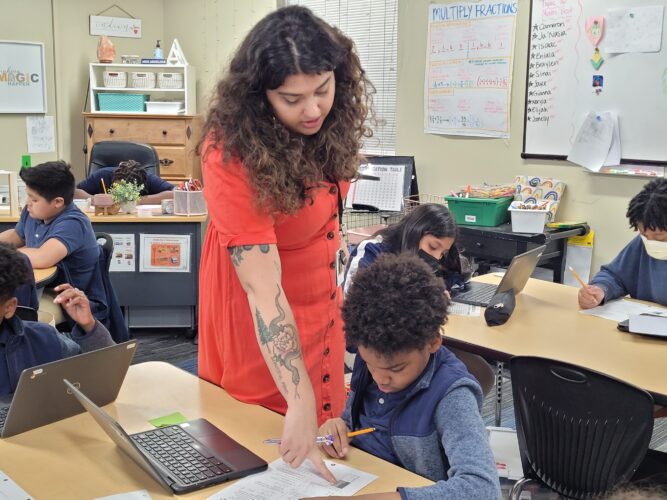

Paramount instead wants teachers to spend little class time on lectures, often just the first 15 minutes. Students then work independently as teachers step in to help students one on one or in small groups.

“It makes our classroom look pretty boring,” Reddicks joked.

But having students work in class means little to no homework, which is an intentional strategy so that students with tough family or living situations still do well.

“They’re getting all the work done during the school day,” Reddicks said, when teachers can immediately correct errors. “So if they go home at night, and they don’t have any parental support, they can still come back tomorrow and be just fine.”

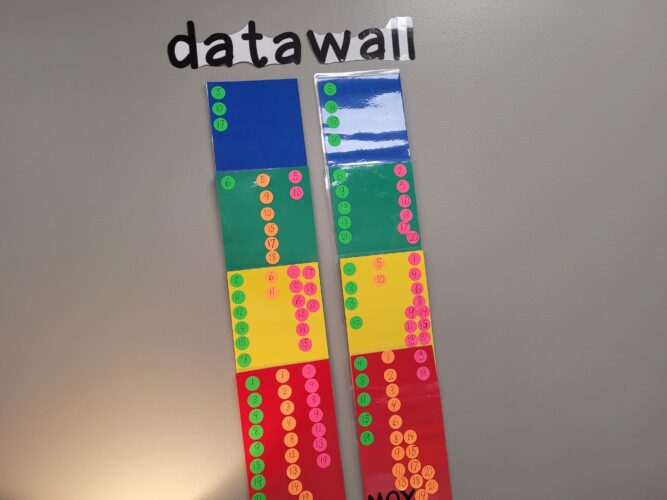

The schools closely track how well students master skills they are taught.

Teachers have a training academy in which new teachers are mentored by veterans and veterans are helped with either advanced teaching or administrative skills.

And Paramount bought laptops for third graders and up even before the pandemic, both to improve learning but also so students could be familiar with them and score better on state tests.

It’s working. In 2016, Paramount Brookside was lauded as one of the top 10 schools in the city at raising scores of poor students closer to affluent ones using the Education Quality Index, an effort of multiple non-profit organizations looking at national achievement gaps.

Last year, the Indianapolis Public Schools highlighted Paramount as a city leader in closing learning gaps between Black and white students. Proficiency rates at all three brick and mortar Paramount schools — students proficient in both math and English — are several times higher than Indianapolis Public Schools for Black, Hispanic and economically challenged students.

In the most recent state test results, released in July, between 34 and 57 percent of Black students were proficient in both English and Math at the three in-person Paramount schools, compared to just 5.4 percent in Indianapolis Public Schools.

For students receiving free or reduced lunch, 38 to 58 percent were proficient in both at the three Paramount schools, compared to just eight percent in the district.

Those scores, as well as a growing reputation, have won over Joe Bowling, executive director of the Englewood Development Corporation, which serves the neighborhood where Paramount opened one of its new schools. Along with helping to renovate and reuse a shuttered Duracell battery factory that was a neighborhood eyesore, he said the school has become an asset to the community

“The Paramount schools draw lower income households and yet the test results and the achievement seems to be there,” he said.

The scores for Black students also drew parent LaToya Tahirou after she grew frustrated with a district school.

“Some kids aren’t getting the same opportunities as other kids as far as quality of educators, quality of curriculum, quality of just the environment at the school as a whole,” she said. “I think Paramount stands above a lot of schools and their city as far as it pertains to educating low income black and brown students.”

That has led to some calls for the Indianapolis Public Schools to share more tax money with schools like Paramount so they can expand and help more students with challenges. Brandon Brown, CEO of Mind Trust, a philanthropy that supports education issues in the city, wants more money for charter schools overall so that students of color who use them heavily can have better opportunities.

Even without extra funding, Paramount still creates an unusual atmosphere for students, with all its “bells and whistles.”. Schools have their own coffee shops that deliver free drinks to teachers in their classrooms. Paramount Brookside has its own planetarium that students in the other schools can visit. The hallways display prints of art by Vincent Van Gogh, Rembrandt and Renoir, but also artists of color like Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Jean-Michel Basquiat. All have QR codes next to them so students can easily link to more information about the artist and piece.

“There’s some real intentionality around our diversity,” Reddicks said. “I’m a huge impressionism person so I made this space just so I can be happy. But for the kids, it’s more about the diversity of artists and the types of art.”

The floors are all carpeted to reduce noise and distractions.

And both Paramount Brookside and Paramount Cottage Home have miniature barns and gardens, where a full time farm manager tends the plants and goats and chickens to help students learn. The goats milk is then processed into cheese in a separate room at the school and sold at farmers markets and some local grocery stores.

The cheese is a passion and hobby of Reddicks, a self-described “cheese nerd,” who learned to make specialty cheeses after finding few he liked in Indianapolis markets. He soon realized that a commercial kitchen in the school would let him sell cheeses along with sparking interest of students.

“It became a really cool balance against the hard work in the classroom,” he said. “That’s what I now call scaffolding excitement. We’ve got to scaffold in exciting stuff in all of our different areas outside of the classroom to make sure that for teachers and for students, for parents, they want to keep coming back, even though it’s such hard work.”

But Paramount schools are not farm schools, Reddicks stresses. Teachers create a lesson each quarter that uses the farm to teach other skills, but the school is not a project-based school or one where parents should expect students to have a lot of farm time. The exception is the group of about 20 students at each of the two schools who are hired to work the farm as summer jobs.

“We have to stay really focused academically,” he said. “The farm becomes a great outlet. And it’s exciting. And there’s great things going on up there. And you’re out there every day at recess experiencing it, but it’s not part of the everyday curriculum.”

Inside classrooms, portions of Paramount’s focused academic mission stand out. Color-coded charts on the walls show how each student is faring over the school year in reading and math skills — blue for above grade level, green for at it, yellow for approaching

“Generally, what we see is many of these students in red and move up a yellow, green and blue by the end of the year,” said Kyle Beauchamp, Paramount’s chief academic officer.

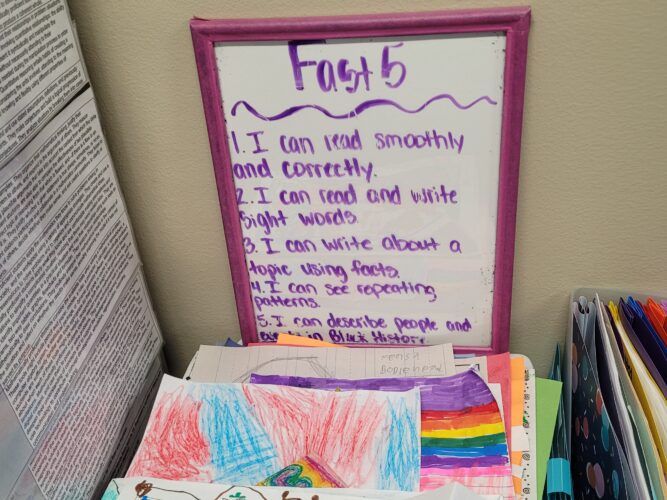

The schools also carefully watch what they call the “Fast Five,” five skills a teacher focuses on that week.

If students lag, the school urges them to attend two-hour afterschool tutoring sessions five days a week.

The chain has long term goals itself. Reddicks hopes to have 10 Paramount schools by 2030 and is well underway toward that goal. Along with the three schools in Indianapolis, Paramount has taken over closed schools in both South Bend and Lafayette and is fixing them to open in the fall.

The schools received a surprise $3 million gift in 2022 from author and philanthropist MacKenzie Scott of the Amazon fortune that will help pay for the expansion.

Paramount is also close to naming a site in northern Indianapolis for the new school it is creating with the Girl Scouts. Girls IN STEM Academy will mix portions of the Girl Scouts’ STEM programs with Paramount’s academic model, though students won’t be scouts.

That school will also continue Paramount’s connection with Purdue Polytechnic High School, another star school chain created by Purdue University with two locations in Indianapolis and a third in South Bend. Reddicks says he has no interest in trying to create Paramount high schools, but Paramount Englewood, a middle school, shares a building with one of the Purdue Polytechnic High Schools so students can easily shift to that school once they finish middle school.

Purdue Polytechnic is also helping Paramount and the Girl Scouts with IN STEM.

“We see their older students serving as role models, mentors, with our K-8 girls,” Shockey said. “It’s not going to be a must-do feeder model, but obviously Purdue hopes that by creating this network with the K-8 girls that by the time they’re ready to choose a high school, they’ll strongly consider Purdue Polytechnic, and maybe before they wouldn’t have even known about it.”

Reddicks said he hopes the new schools will convince others that Paramount’s success is not a fluke and that expansion elsewhere is worthwhile.

“I think we can take that model and put it anywhere and be successful,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)