Pandemic Notebook: The Death of My Grandfather in China Brought Home the Pandemic’s Toll in Isolation and Loss

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The day I found out my grandfather died, I cried so hard I threw up. Two days later, I went back to school.

I walked through the front doors holding back tears. It wasn’t that I felt uncomfortable crying in public. I just wanted to avoid combining a mask with a runny nose.

First period went by without a hitch. Second period was on track to end the same way until I decided to verbally respond to an email from my history teacher. At the time, my school had a hybrid schedule with three rotating groups. For example, if Cohort A was in school on Monday, Cohorts B and C would do school virtually.

The night before coming into school that day, I’d sent my teacher a message. The email read: “Hi Mrs. Hollman, yesterday after school, I found out that my grandfather had passed away. I just wanted to let you know in case I ever started crying during class. I’m trying my best to hold myself together, but I just can’t help it.”

She responded: “So sorry to hear that. It sounds like you were close. How old was he? When’s the funeral? If you need to turn off your camera or step off Zoom any time I understand.” Two simple questions, and yet I couldn’t send a reply. Looking back, I realize that I waited because the grief trapped in my body had nowhere to go.

Why? That’s a long story. It makes me think about how hard the isolation of the pandemic has been on kids my age, particularly those who had previously battled loneliness and depression.

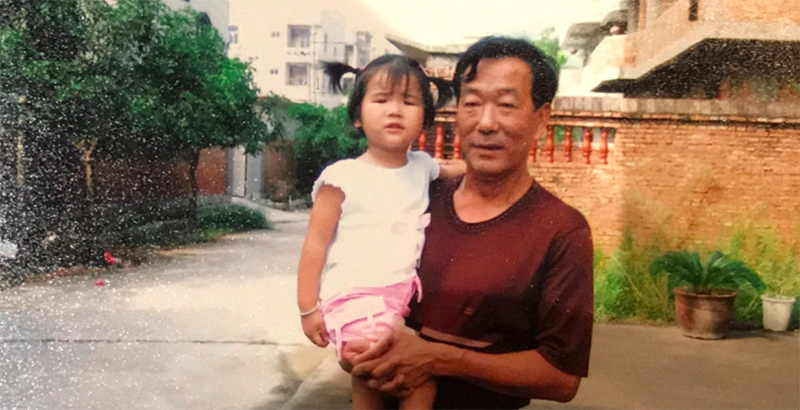

When I was born, my parents lived in a tiny apartment in Brooklyn. They wanted to move to the suburbs to raise their family but hadn’t saved up enough money. With only my dad working (and my mom staying at home to take care of me), my parents eventually decided to send me to China to live with my grandparents. By the time my parents finally bought a house in the suburbs, I was five years old. At the time, moving back to the United States was an unwelcome and drastic change. I didn’t understand a word of English, and my grandparents were all I knew. They took me to the park, cooked my favorite meals, and tucked me in at night.

For as long as I knew him, my grandfather had a nicotine addiction. He started smoking cigarettes at fourteen, and the problem only worsened as he got older. By the time he reached his sixties, he could not walk up a flight of stairs without heaving. He never had cigarettes in his pockets, but it was hard not to notice the smell. During my stay in China, I followed him everywhere to make sure he didn’t smoke. I even spied on him from behind curtains. Once, I caught him hiding a cigarette on the ledge of the stone wall that surrounded the house. After he walked away, I rushed out and stood on my tippy toes, feeling for the cigarette along the length of the wall. When I found it, I ripped it in half, emptied out the contents, and left it there for my grandfather to find.

I did annoying things like that a lot, but my grandfather never raised his voice at me or told me to leave him alone. He’d just chuckle and call me a “bad egg.”

Unlike my relationship with my grandfather, the one I share with my parents has always been tense. My parents are what you might consider “typical immigrants.” They’re Chinese nationals who left in their early twenties to pursue a better life for themselves and their future children. For them, discussing mental or emotional health has never been easy or necessary. When you grow up splitting a single egg with your siblings, there is no time for “feeling blue.”

Whenever I struggled with difficult emotions, my parents did as well. Loneliness was met with anger, sadness with dismissiveness, fear with biting words. I have never felt comfortable speaking to my parents about my emotional or mental wellbeing, and only do so when I want to feel worse than I already do. In other words, never. It doesn’t help that my parents are barely home: They leave for work hours before school ends and come home minutes before I’m about to fall asleep. I know that owning and operating a restaurant isn’t easy, but I wish I had time to say more than “good morning” and “good night.”

My brother isn’t exactly someone I can confide in either. He’s five years younger than I am, and didn’t have the same close relationship with our grandfather. To him, grandpa was some old guy who lived on the other side of the world. I didn’t know how to explain to him, or any of my friends, that knowing grandpa isn’t somewhere on earth felt like a part of me was being violently ripped away. So I stayed silent, isolated, unsure of how to cope.

At the end of second period, once all the students left, I turned to Mrs. Hollman and said, “He was about to be eighty.” I remember tightly clenching my hands, digging my nails into my palm. But once the first tear broke free, the rest followed in an unbroken stream. I then blubbered out everything I had been holding in. I finally had someone to listen to all the words I wanted to say. I don’t remember exactly what Mrs. Hollman said. No quantity or quality of words could ease the pain, but that’s okay. At least she listened.

After arriving at my next class, I quickly asked to go to the bathroom so I could clean myself up. Luckily, I was the only person in there — awkward stares and questions avoided. I blew my nose, wiped my mask, put it back on, and tried all the methods I knew to stop from crying.

I have these memorized because in freshman year, when my depression and anxiety were unmanageable, I’d often randomly burst into tears. I think every one of my teachers from ninth grade saw me cry at least once.

The first time I acknowledged my mental health problems was with my eighth grade English teacher. A toxic friendship, low self-esteem, and persistent feelings of failure made me wish I could stop waking up in the morning — at the age of fourteen. In school, I would stare at a wall without noticing that an entire period had gone by.

My English teacher at the time, Mrs. Doane, noticed my odd behavior and pulled me aside after class one day to ask whether I was okay. The answer was no, but that’s not what I said. Mrs. Doane didn’t believe me, and I’m glad she didn’t. By continuing to use the power of, “How are you?” she gradually got me to open up. And through our conversations, I learned that I needed professional help.

It took me three years of consistent, agonizing steps in the right direction — steps so microscopic that they didn’t seem to exist at all— before I finally felt I was meant to live.

Death from COVID-19 complications isn’t something most students have to worry about. But the consequences of pandemic-induced social isolation shouldn’t be underestimated. A surge of student suicides in Clark County, Nevada, convinced district officials that schools need to reopen as quickly as possible. New research from the Centers for Disease Control found that emergency room visits for suspected suicide attempts among teens increased 31 percent last year compared to 2019; for teen girls, the attempts were over 50 percent higher.

Reaching out to students struggling with depression may seem next to impossible when teachers and administrators have so much to deal with as a result of the pandemic. But I know I wouldn’t have made it this far without my teachers.

Students certainly need additional help. I have an idea about how technology can be used to open a new frontier in mental health support. Students, with the help of their guidance counselors, could launch peer-support video conferences. Although these conferences wouldn’t replace professional counseling, they could help students cope. Any time during lunch or even after school, a student who is struggling could join such a group and talk with a fellow student who is there to empathize, ask questions — and most importantly — to listen.

It’s been five months since my grandfather passed. Things have gotten better. Sometimes an entire day passes where I don’t think of him at all. But on the days that I do, I feel a deep sense of longing that nothing can alleviate.

I’ll be a senior next year, so I’ve started looking at colleges, thinking about prospective majors and planning my future. But although life goes on, I’d give anything to call my grandfather again and tell him one more time to stop smoking.

Cindy Chen is a junior at James Caldwell High School in Caldwell, New Jersey.

“Pandemic Notebook” is an ongoing collection of first-person, student-written articles about what it is like to live through the coronavirus pandemic. Have an idea? Please contact Executive Editor Andrew Brownstein at Andrew@The74million.org.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)