Pandemic Catch Up: What Will it Take for Left-Behind Students to Learn to Read?

Teachers must meet California grade-level standards for instruction, leaving many wondering if some students will ever recover from learning loss

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

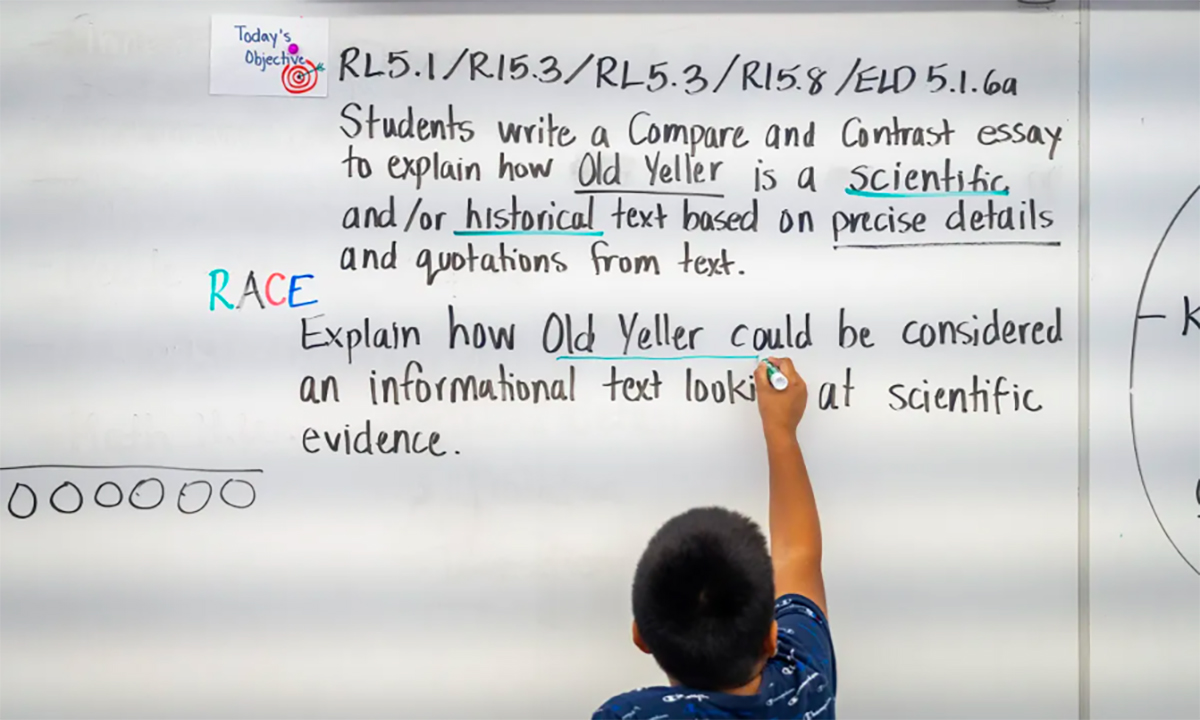

Roxanne Grago’s fifth-grade students at Lake Marie Elementary should be able to read a short story, analyze it, and support their analyses with examples from the text.

But Grago said that during school closures and other pandemic-era disruptions, students fell behind academically. Today, they struggle to interpret the meaning of a story because they didn’t master the basics of reading. Many didn’t receive adequate instruction in phonics, the practice of sounding out words, when they were in full-time remote learning in third grade.

“That’s another reason why my students aren’t progressing,” Grago said. “You don’t teach phonics in fourth and fifth grade.”

Across California, teachers like Grago are struggling to get their students back on track after they missed large chunks of reading instruction in third grade — a pivotal year for literacy, when students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” Reading at grade level by third grade ensures they can understand their science and history textbooks in later grades.

The stakes are high for getting students caught up. Studies show that students who can’t read at grade level by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school as well as earn smaller salaries and have lower standards of living as adults.

“When students missed the most crucial year for learning to read, the system was never set up to help support them,” said Shervaughnna Anderson-Byrd, the director of UCLA’s California Reading & Literature Project. “They came back to a system that assumed they had received instruction.”

“That’s another reason why my students aren’t progressing. You don’t teach phonics in fourth and fifth grade.”

Roxanne Grago, fifth-grade teacher at Lake Marie Elementary

State standardized test data released in recent months show Grago isn’t the only teacher trying to help students recover fundamental reading skills. California’s Smarter Balanced tests are given to almost all students in grades three through eight and grade eleven every year. They measure whether students have mastered state standards for math and English language arts. Students take the assessments every spring with scores released the following school year, usually in the fall.

The test was canceled in spring 2020 and was optional in 2021. The spring 2022 test results provided the first comprehensive look at how much students fell behind since the start of the pandemic.

Both math and English language arts scores dropped, but no other subject controls how well students learn other subjects than foundational reading. Among all grade levels, state data show third-graders saw the steepest declines in English language arts: Comparing 2019 to 2022, the share of third-graders meeting or exceeding standards dropped from 49% to 42%.

Among California school districts that tested more than 100 third-graders, South Whittier Elementary’s third-graders saw the biggest drop. In 2019, 36% of third-graders in the district met or exceeded English language arts standards. In 2022, that number plummeted by more than half, to under 18%.

Remote learning and pandemic disruptions had disparate impacts for English learners and low-income students, who are more likely to be Black and Latino. At South Whittier, about a third of students are English learners and nearly 90% of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Closing the achievement gap for Black, Latino and low-income students has long been the goal of policymakers in California. Under the state’s education funding formula, public schools serving more low-income families, English learners and foster children get more money from the state. But students in those groups were more likely to fall behind during remote learning due to a lack of internet access, language barriers and mental health challenges.

In the early months of the pandemic, teachers taught lessons to faces on computer screens, but some students turned their cameras off. While some students managed to keep up, some had to work out of cars in Starbucks parking lots for a reliable Wi-Fi signal. And others just disappeared from this virtual version of school, forced to take care of siblings or work to help pay rent.

Statewide, the achievement gap between Latino students and white students on the Smarter Balanced tests grew slightly. Latino students in third grade saw a slightly steeper drop in test scores than third-graders overall. They went from 38% in 2019 to 31% of students meeting or exceeding standards in spring 2022. Black third-graders saw less of a decline, but they have the smallest percentage of students who met or exceeded English language arts standards, at 27% in spring 2022.

“This becomes about social justice and race,” Anderson-Byrd said. “Our Black and brown children are suffering the most with low reading scores. Especially our Black children.”

Two years ago, Grago’s students were in third grade and should have mastered phonics and started reading for comprehension. But that school year, Lake Marie Elementary School in the South Whittier School District had moved to full-time remote learning, a period of tumultuous and disrupted instruction for students statewide.

Grago had the same students last year when they were in fourth grade. She said her students have gotten closer to reading at grade level since last year, but about a quarter of them still struggle with phonics.

“We did very little phonics instruction last year, but I should’ve done more,” Grago said. “Now they definitely need it.”

Snowballing learning loss

Even though many students are far below grade level in reading ability, California’s education system requires teachers to meet specific instruction standards for each grade. Because the state assesses districts on these standards through the Smarter Balanced tests, teachers feel unable to spend more time teaching students the material they may have missed in past years.

“Our system is not designed for the individual child,” Anderson-Byrd said. “Our system is designed for the system.”

The South Whittier School District requires fifth-grade teachers to grade students on 54 standards across all subjects. In English language arts, students should be able to compare two characters from a story, synthesize information from multiple sources and identify the main ideas of a written work. Grago said these requirements leave little time for catch-up.

“I’ve been looking at what they have to learn in fifth grade, and it’s harder to fit in phonics,” Grago said. “It just keeps snowballing.”

“I feel bad handing the middle school teachers these students. Because I don’t know how they’re going to make up the losses.”

Emily Thompson, sixth-grade teacher at Lake Marie Elementary

Educators and experts have widely referred to this missed instruction as “learning loss.” Teachers tasked with helping students catch up while meeting mandated standards feel students will never recover what they lost, especially in literacy.

Emily Thompson, who teaches sixth grade at Lake Marie, said the typical student in her class reads at a fourth-grade level. Up until last month, the average reading level for her class was third grade. She said she’s “genuinely afraid” of her students’ inability to read at grade level before they move onto middle school.

“I feel bad handing the middle school teachers these students,” she said. “Because I don’t know how they’re going to make up the losses that I couldn’t make up.”

Thus far, teachers say absences and positive COVID cases are down this school year compared to January’s omicron surge, but students still have a hard time focusing in class after a year of learning from home.

Thompson’s students sit on the ground in front of her facing the white board. They’re reading a novel together called “Esperanza Rising,” about a Mexican family that immigrates to California during the Great Depression. One of her students is learning English and follows along with a Spanish version of the book. There are several students talking to each other instead of paying attention as Thompson tries to start a discussion about the novel’s characters.

“In terms of COVID-related disruptions, this year has been much more stable,” she said. “But I would say student behaviors have been worse. It makes it more difficult to teach.”

Getting extra help

Carmen Gonzalez is the reading interventionist at Lake Marie. She sits at the head of a semi-circular table with half a dozen students around her. She sounds out words on a card while her students repeat after her. Students at Lake Marie who are furthest behind get pulled out of their classrooms and work with Gonzalez for half an hour a day.

“When you enter a first-grade classroom today, it feels like you’re entering a kindergarten classroom,” she said, describing the literacy levels of current students.

It might take a couple of more years to undo the academic fallout of the past three years and get students reading at grade level, Gonzalez said, but she’s encouraged by the progress her students have made this year.

“Children are like sponges,” she said. Before the pandemic, they used to be more embarrassed about having to meet with her, but now getting extra help has become more normalized.

“They may feel that, ‘Oh, I’m going there because I didn’t do well on a test,’ ” she said. Eventually, Gonzalez said, students adapt to and start to enjoy the ritual of working with her.

But Grago said students need much more than half an hour a day.

“I don’t think it’s a significant amount of time,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s really making a difference.”

Students can also stay after school for extra help, but Grago said only about half of the students who really need it will stay. In general, making extra help optional outside of the school day creates inequities. For example, students whose parents have flexible schedules will be more likely to get rides home if they stay after school than those who don’t.

Intervention should not be optional, Anderson-Byrd said. “It means that you’re already selecting some students to fall behind.”

Thompson said that last year, the school had three reading specialists, but two moved to teaching classes. The school hasn’t been able to fill those positions, leaving Gonzalez as the sole specialist.

“We’re kinda stuck. We do the best we can,” Thompson said. “But truly we aren’t doing enough because there aren’t enough resources.”

Anderson-Byrd said it’s possible to recover learning loss while teaching students new material. She’s seen some principals use COVID relief funding from the federal government to hire several reading specialists and conduct frequent assessments of all students.

Some schools focus on literacy across all subjects. Science, math and social studies instruction all can be opportunities to focus on reading, Anderson-Byrdd said.

South Whittier School District administrators are confident that test scores will bounce back closer to pre-pandemic levels by the spring. Rebecca Rodriguez, associate superintendent of educational services at South Whittier School District, said the 2021-22 school year was far from normal and not a good baseline.

“You can’t have a knee-jerk reaction to last year’s scores,” Rodriguez said. “The scores are going to be different this year.”

Experts agree that last year’s test scores don’t determine the fate of students who endured the pandemic.

“We need to look at the data four years out since the start of the pandemic to see how persistent this drop-off is,” said P. David Pearson, an education professor at UC Berkeley. “We need to look at the current fourth-graders two years from now.”

In the meantime, the current crisis in literacy presents an opportunity to rethink reading instruction, Anderson-Byrd said. Most aspiring elementary school teachers receive about 10 weeks or one semester of training in English Language Arts, which includes reading and writing, during their one-year credentialing programs. She said reading instruction deserves a year-long course with more emphasis on developmental psychology, which focuses on how young brains work.

Additionally, because California serves so many English learners, Anderson-Byrd said reading instruction courses should also focus on language acquisition. That means first training teachers on better assessing their students’ language abilities and identifying students who need extra help from language specialists.

“I hear a lot of teachers saying they just want to get back to normal, but for some kids that’s two years of instruction they missed,” Anderson-Byrd said. “There is no normal. It’s almost criminal to throw them back into the system and expect things to be normal.”

This story was originally published by CalMatters.

CalMatters reporter Erica Yee contributed to this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)