Oregon Fails to Turn Page on Reading: Using Flawed Teaching Methods

The state's 15 educator preparation programs offer vastly different reading instruction methods to future teachers, and some teach flawed methods.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Editor’s note: Reporter Alex Baumhardt worked almost exclusively on this series for more than four months, starting in January. The project involved extensive research and interviews with more than 80 people, including state and local leaders, teachers, parents and students. She collected data and historical documents through records requests with state agencies and school districts, and visited schools across the state.

It took Ronda Fritz more than a decade and a doctorate degree in education to learn how to teach kids to read.

Before she became a professor at Eastern Oregon University in La Grande training a new generation of teachers, and before she began a campaign to change reading instruction in eastern Oregon schools, Fritz was a reading specialist in her hometown of North Powder, near the Oregon-Idaho border. Her undergraduate and graduate classes in reading at both Boise State University and Eastern Oregon University were not working. Her students were not improving, and her son in kindergarten was struggling, too.

“I’m a teacher — I’m supposed to be a reading teacher — and I have no idea how to help him or the children that are coming to me every day,” she said. “I was ready to just be done with education. I thought: clearly, I’m not good at this.”

It’s a feeling Fritz hears from many of the teachers in eastern Oregon schools who she retrains in reading instruction.

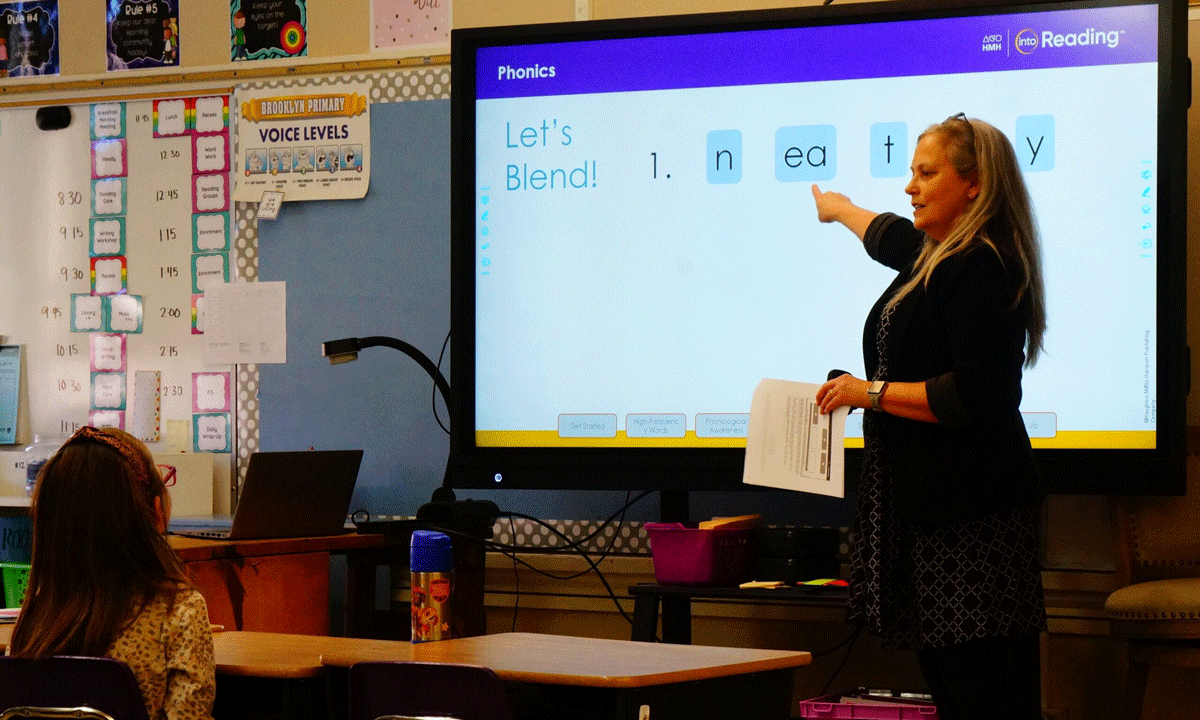

Fritz teaches educators how to teach reading. She does so based on decades of cognitive and neuroscience research that explains how the brain learns to decode and make meaning of written language. This requires correlating sounds with letters and letter combinations, known more broadly as phonics instruction. Her students learn how to build lessons from that knowledge to help kids read more confidently, and to move into writing and comprehension of more complex words and sentences.

Her students learn to teach everyone, from a student with dyslexia to a second grader reading well above grade level. This is not how all newly minted teachers in Oregon are trained today. It’s not even how most would have been trained at Eastern Oregon University five years ago.

The university, like many that train teachers across the U.S., has faced mounting pressure from alumni, parents, politicians and school districts in the last few years to ensure it graduates teachers knowledgeable in methods of reading instruction proven to work for all kids.

Morgan Whitney, a teacher for Portland Public Schools and a 2013 graduate of Portland State University’s graduate teacher program, said the type of instruction she and her peers got in reading at the university depended entirely on which professor they were assigned. She ended up paying thousands of dollars for specialized training after earning her degree, and eventually a second master’s degree in the science of reading at a different out-of-state institution. She is still paying off the loans she took out to support all of this.

“I’m not angry. I just really want them to start doing better,” she said of Portland State. The university has conferred more education degrees than any other public institution in the state during the last 15 years.

The nearly 10,000 elementary school teachers in Oregon learned different methods for teaching reading depending on where they went to college.

Today, Oregon’s 550,000 students have been left to contend with these instructional differences. About 40% of fourth graders and one third of eighth graders scored “below basic” on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as the “nation’s report card.” That means they struggle to read and understand simple words.

In May, Gov. Tina Kotek issued an executive order creating a commission that will spend the next year investigating and evaluating reading instruction at the state’s educator preparation programs and whether it aligns with decades of research on how best to teach reading. The goal is to update the teacher licensing process so all new teachers licensed in Oregon demonstrate they understand how best to teach all kids to read.

“If you want to teach in Oregon after this is all said and done, you have to meet this skill set,” Kotek told the Capital Chronicle.

Anyone who has prepared to teach kindergarten through fifth grade in Oregon during the last seven years received some training in teaching phonics, according to compliance reports the universities sent to the Teacher Standards and Practices Commission in 2016 and 2017. But most elementary teachers-in-training take only one or two courses on reading instruction, and are more immersed in theory than in linguistics and the rules of written language, according to those reports and to interviews with graduates and professors who spoke with the Capital Chronicle.

Some even learned flawed methods as part of an approach to teaching reading called “balanced literacy.” Some methods include teaching students to guess at unknown words, to memorize words and use pictures rather than spending time decoding them and sounding them out. Some even learned that overemphasizing phonics skills would turn kids away from a love of reading.

While some Oregon professors have led the nation in reading research during the last 60 years, individual professors at the state’s 15 education colleges and universities decide which theories and methods they believe are most effective, and not all of those methods have been rooted in the decades of reading research and science.

“Professors are free to teach whatever they choose,” said Edward Kame’enui, a retired professor emeritus and special education researcher at the University of Oregon in Eugene who helped found the university’s Center on Teaching and Learning. “To me it’s really a serious issue of public trust. The university ought to be relying on science to promote the content for which students are paying tuition. Somebody needs to sue the colleges of education, including my own.”

Kame’enui’s former colleague Doug Carnine, a professor emeritus at the school, feels similarly.

“At a systemic level, the single biggest problem is colleges of education,” Carmine said.

At a number of schools around the state, change is under way among faculty. But others have doubled down on flawed methods. According to a recent analysis of reading instruction at public teacher colleges by the National Council on Teacher Quality, nearly all in Oregon are failing.

Quality control

The Teacher Standards and Practices Commission, Oregon’s teacher licensing agency, is in charge of ensuring graduates of Oregon’s teacher prep programs are prepared to teach reading in a classroom.

So in 2015 and 2017, when the state Legislature passed laws requiring Oregon’s educator preparation programs to ensure all kids could read by the end of third grade and to train teachers to screen for dyslexia and other reading difficulties, the commission was in charge of ensuring the education programs complied. All of them submitted lists and descriptions of literacy courses and textbooks to the commission, and all of the schools passed. Anthony Rosilez, director of the licensing commission, said in the end the state’s mandate that universities teach “evidence-based” reading instructional strategies was too vague.

“The challenge (is) what’s been considered ‘evidence-based reading instructional strategies’ has varied through time and evolved through time,” Rosilez said.

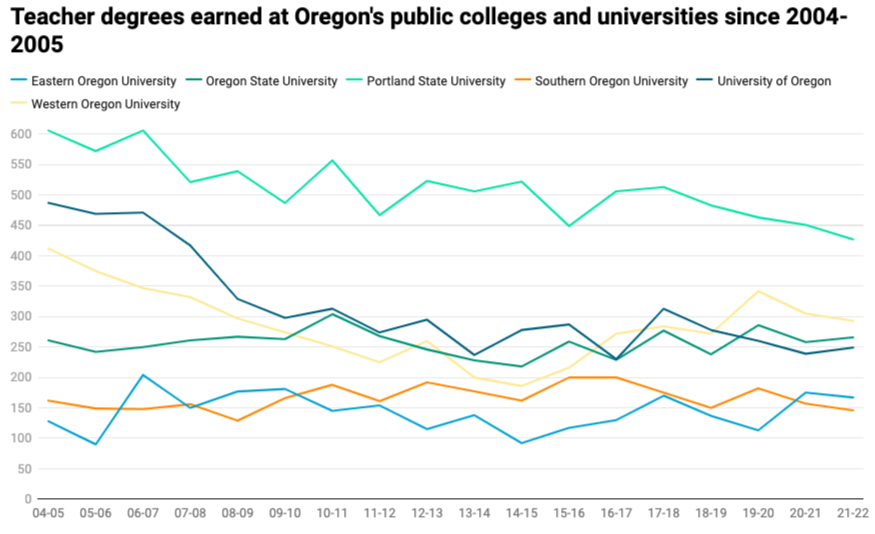

Oregon’s education agencies do not track where licensed teachers graduated or where graduates of the state’s universities end up teaching. The Higher Education Coordinating Commission keeps track of how many people graduate from education programs at the state’s public universities, but not all will go on to become licensed teachers. During the last two decades, about one-third of all teacher credentials conferred by a public university in the state were from Portland State University. Officials from the Teacher Standards and Practices Commission estimate that at least half of Oregon’s teachers graduated from in-state schools, but they do not have data.

The licensing exam that the commission issues, and that all future teachers must take, ultimately sets the standards for what they have to know.

Until September of 2021, the exam to get certified as a reading specialist in Oregon included testing teachers on a “balanced approach to literacy” and on methods — called “cueing” — that involve getting students to guess at words and use pictures. It essentially ensured that teachers were taught flawed reading instructional methods in college so they could pass the exam. The new version teachers have taken since September 2021 no longer tests them on cueing, or even mentions balanced literacy.

Failing grades

Most Oregon teacher preparation programs have received failing grades for reading instruction from the Washington, D.C.-based National Council on Teacher Quality, which has been convening panels of experts to review programs since 2013.

The colleges get a grade based on whether they are teaching five foundational reading skills, including phonics, in accordance with scientifically based methods. They also get reviewed on how many hours teachers are required to spend learning reading methods, on how their knowledge is tested and assessed and the kinds of opportunities they get to practice what they’ve learned in the classroom.

“Most teacher prep programs aren’t giving teachers the tools they need to help kids learn to read,” said Heather Peske, president of the council.

Today, it released its latest grades. Undergraduate and graduate programs at five of the state’s six public universities were evaluated, and nearly all got an “F.” None of the private colleges participated in the latest review, and Western Oregon University in Monmouth denied the council’s public records requests for information about its teacher degree programs. Leaders at Western, the University of Oregon, Portland State University and others have criticized the council’s methodology for not being comprehensive enough.

But one college shot up the ranks after spending the last three years transforming its reading instruction to be aligned with the science of reading: Eastern Oregon University.

‘Noticeable differences’

In 2016, Fritz, the Eastern Oregon professor, graduated from the University of Oregon with a Ph.D. in special education. She studied under academics who had previously been architects of some of the largest state and national reading initiatives.

At the time, she was also supervising student teachers at Eastern Oregon University, and teaching one literacy class to students preparing to teach kids who were learning English as a second language. But in 2019, a new dean took over at the college of education, and he asked Fritz to come up with a new course in special education and literacy. She started developing a reading clinic modeled after one in Washington D.C., where teachers in training could practice reading interventions and instruction on individual students. She started tutoring her colleague Amanda Villagómez’s daughter as she developed the model.

Villagómez was in charge of undergraduate reading instruction at Eastern, and even in this role, was struggling to help her first grader learn to read. It mirrored Fritz’s own experience with her son years prior.

Villagómez had earned her undergraduate and master’s degrees at Eastern and a doctorate from Boise State University. She had been taught to teach phonics, but not to the students struggling most, she said. She’d also been taught other strategies, like getting kids to guess at words or use pictures. Villagómez said the exam she took to get her reading credential when she was a classroom teacher in Ontario tested her on her knowledge of strategies she knows now are flawed.

When she saw the gains her daughter was making with Fritz, she was astonished.

“There were noticeable differences fairly quickly,” Villagómez said. “I would say my daughter always loved having books and talking about books, but it was just the sense of her being able to read with confidence and to read on her own.”

When Villagómez moved into a new role leading the master’s in education program at Eastern, she asked Fritz to take over her role directing reading instruction for future teachers. Fritz got to work incorporating all of the reading science she had learned.

Across the state at Western Oregon, change was also underway. Marie LeJeune, who runs the undergraduate teacher preparation program at the school, said the 2017 legislation requiring colleges to train teachers to screen for dyslexia and reading difficulties led her and a number of newer faculty to incorporate more methods aligned with the science of reading into instruction.

Karren Timmermans, who runs literacy instruction in the teacher degree programs at Pacific University in Eugene, also took a hard look at her reading methods course after the 2017 legislation.

Timmermans said she still relied on cueing, on “that guessing game, of guessing words and looking at the picture.” She signed herself up for 100 hours of Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS training, developed by reading expert Louisa Moates. The training is steeped in the science of reading and in phonics instruction and the fundamentals of written language. She also immersed herself in research about how special education teachers approach reading.

Special education experts have found that more than 90% of students across learning abilities can learn to read if they are taught in ways that align with the science. She eventually got Pacific approved by the Oregon Department of Education as one of two universities in the state — along with Eastern Oregon — to offer a dyslexia concentration and certificate program.

At Southern Oregon University in Ashland, literacy and special education expert Sasha Borenstein was hired to teach an elective reading science class for English and education majors earlier this year. Borenstein, who teaches the class remotely from her home off the coast of Maine, initially proposed the class 14 years ago when she moved from Los Angeles to Ashland.

“I went to the university and I went to the special education department and I said: ‘This is what I do. Can I be of any help?’ And nobody took me up.”

The school is not making it a required course for all students in the teacher education program, but is considering creating a science of reading endorsement, a sort of additional credential that acknowledges expertise and that can be added to a teacher’s license.

Divide on instruction

Sylvia Linan-Thompson, an associate professor of special education at the University of Oregon said there is a historical divide between general and special education professors on many campuses.

“A lot of this research comes from special education,” she said of the science of reading. “General education programs haven’t always been very quick to accept them.”

Despite the growing research supporting robust and intensive phonics instruction, and the research showing the methods such as memorization, using pictures and guessing at words based on context can actually have long lasting negative effects on reading ability, administrators at many Oregon universities remain wary of change.

Audrey Lucero, an associate professor of language and literacy education in the school’s general educator program, said she teaches students preparing to be K-5 teachers in a balanced way. This includes phonics instruction and learning those foundational reading skills, as well as those guessing strategies, such as using pictures to identify words.

“The majority of kids that they’ll be working with are typically developing kids,” she said of her college students. “Of course, some of those kids will have learning disabilities. Hopefully they’re being served by special education.”

Lucero believes teaching phonics explicitly is important, but focusing too heavily on it can turn kids off of reading or take up valuable time that could be spent learning to comprehend ideas and meaning from the text.

“This has happened over and over throughout history that kids in the highest-needs schools get the most rote instruction and do not ever get to the point of critically engaging with text, which is, after all, what literacy is about,” Lucero said. “I’m not convinced that based on the research, based on my experience, based on the 20 years I’ve spent in classrooms, that all we need is more decoding practice.”

She shares this view with Leigh VonDerahe, program director for the reading intervention program at Lewis & Clark College in Portland.

“We’re sticking firm with the balanced literacy approach to teaching reading,” VonDerahe said. She is concerned that the science of reading is a push for phonics-only instruction.

“The implications for that are: We might have students who can read but do they read? Do they continue to be lifelong readers?”

Kimberly Campbell, chair of the master’s in education program at Lewis & Clark, said by placing too much focus on phonics and decoding skills, teachers sacrifice teaching comprehension skills.

“It’s strictly about letter sounds, and that’s troubling and concerning,” she said. “So, when we look at research, we look across a broad range of research that considers all of the components of reading that are part of balanced literacy.”

But Campbell’s approach to reading instruction was troubling to Alicia Roberts Frank, who worked with Campbell in 2013. Roberts Frank was director of Lewis & Clark’s special education program. She said she and Campbell had conflicting ideas of what “evidence-based” reading instruction meant, and she had little support within the college for trying to move instruction away from flawed methods and strategies.

“I can’t tell you how many former students of theirs came to me saying: ‘I didn’t learn how to teach these kids to read.’ It was very frustrating,” Roberts Frank said. Three years into the job, her contract was not renewed, and today, she’s a dyslexia specialist and regional administrator for special programs covering five school districts in southwest Washington.

She’s created an online science of reading training program, and retrains teachers across the state in the methods she wasn’t able to instill at Lewis & Clark. During the pandemic, she created an online program that reached more than 2,000 teachers across the U.S. and Canada.

Taking responsibility

Those leading changes in reading instruction at their universities say the colleges bear some or most blame for low reading proficiency and a lack of reading gains around the state during the last two decades.

Kame’enui, who helped found the University of Oregon’s Center on Teaching and Learning, said universities bear the greatest blame.

“When people exact this notion that they are free to teach whatever they choose, then it violates to me the public trust of a public university,” he said.

Timmermans, at Pacific, said she sees it as a shared responsibility among colleges, school districts and curriculum publishers.

“I think public schools have a responsibility to ensure that the teachers have access to the sort of curriculum that is well-researched and scientifically based; teacher education programs have a responsibility to stay current in the field and ensure our teachers are well prepared; and the textbook publishing companies need to ensure that the scientifically supported methodology is being published so that teachers have access to those resources, even after they leave teacher education programs,” she said.

Whitney, the Portland State graduate and Portland Public Schools teacher, said it’s the colleges’ responsibility to provide teachers with sound, comprehensive training in teaching reading before they have a classroom of their own. Today a growing number of Oregon districts, including Portland Public Schools, are paying for teacher retraining in reading to teach teachers the skills they didn’t get taught in college.

“I firmly believe it should not be the school systems’ job to do that,” she said.

In eastern Oregon, Fritz continues to bring what teachers should have learned in college to the elementary school classrooms where they work. Across the state, Oregon’s public universities are not collaborating on any large-scale change, cross pollinating ideas and experts to improve coursework and instruction in teacher degree programs, according to Fritz. They all compete for state and federal money and are all governed by separate boards.

There aren’t professors or deans at any teacher college in Oregon asking her to speak with students or join discussions with faculty. But a growing number of school districts around the state are asking for her help. Today, she visits schools in eastern Oregon to provide in-person training, and she provides online training for teachers across the state. She helps them use new phonics-based curricula rooted in the reading science, and teaches them how to help students struggling the most.

“I feel like I’ve reached a place in my career where I’m doing what I was meant to be doing,” Fritz said.

She tells these current and future teachers that if they are struggling to teach reading, it is neither they nor their students that are the problem, but the methods they are using or the ways they’ve been taught that need improvement.

She wants to get to them before they give up like she nearly did.

Previous: Part 1: Oregon spends $250 million over 25 years but still fails to teach children to read

Next: Part 3: For Oregon kids, the quality of reading instruction will continue to be left up to schools

This project was funded by the Urang Schuberth family in the Portland area. The Capital Chronicle was rigorous in maintaining a firewall between the project and the funders. States Newsroom, the nonprofit 501c(3) organization based in North Carolina that created and funds the Capital Chronicle, oversaw the project funding.

Oregon Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oregon Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Lynne Terry for questions: info@oregoncapitalchronicle.com. Follow Oregon Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)