Oregon Fails to Turn Page on Reading: Districts to Remain in Charge of Literacy Instruction

With districts, not the state, responsible for improving the teaching of reading, some students will be left behind.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

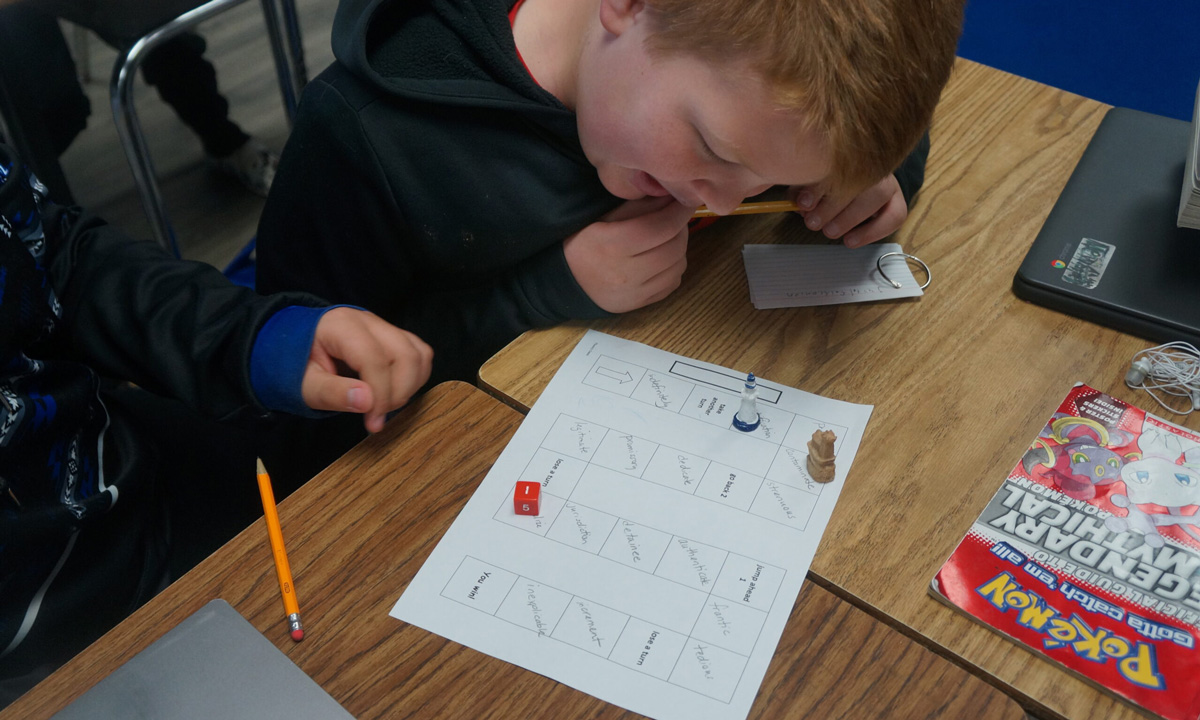

The pandemic pushed teachers at Brooklyn Primary School in Baker City to overhaul how its teachers taught reading.

When kids returned to the K-5 school in eastern Oregon, some of the second graders needed help sounding out the word “the.” Some of the third graders — who were in kindergarten when schools closed — struggled to write.

“They didn’t get to build muscle memory with writing,” teacher Ashley Ballard said. “They didn’t get to regularly hold a pencil.”

The state has spent at least $250 million in the past 25 years to improve reading instruction, the Capital Chronicle found, but has failed many students even before the pandemic.

Before COVID hit, about 42% of Brooklyn students were considered proficient in reading based on state standardized tests. The year students returned, about 32% were considered proficient, tests showed. Kids who were already behind had slipped further, and the teachers and Principal Katy Collier committed to urgent change.

It started with an examination of how they had been teaching.

Brooklyn teachers had been using a curriculum, called Units of Study, developed by Columbia University Professor Lucy Calkins. It and Calkins have come under scrutiny during the last few years following national reporting by journalist Emily Hanford. Some of the methods it teaches have been shown to be detrimental to helping kids read.

It’s also not on the Oregon Department of Education’s list of 15 approved curricula, though the state doesn’t ban schools from choosing teaching materials not on the approved list. It also does not meet expectations for quality reading instruction according to the North Carolina-based EdReports, a nonprofit advocacy group that reviews elementary reading curriculum.

Brooklyn’s teachers were determined to do better.

The road map

Curriculum in any subject is essentially a road map for the teacher, who is driving the car. It guides the day-to-day lessons and experiences a teacher will impart, down to slide decks, assignments and classroom activities. Oregon’s strong tradition of “local control” means teachers, administrators and locally elected school board members decide what curriculum to use and students are stuck with their choices. Because the education department doesn’t track what curricula schools use, and doesn’t intervene if reading proficiency declines or doesn’t improve, it’s up to individual districts and their school boards to change.

Some, like those in eastern Oregon, are doing so on their own. A growing number of districts — in response to COVID learning losses and pressure from parents, advocates, politicians and teachers — are taking on the enormous work of overhauling reading instruction so that it’s being taught in ways that many reading and special education experts know all kids need.

The overhaul involves new curricula and bringing experts, or their courses, to teachers who train voluntarily on weekends, after school and during the summer. Other districts are beginning to explore change slowly.

New Oregon initiative

Gov. Tina Kotek made tackling more than a decade of low reading proficiency among Oregon students a campaign promise. The cornerstone of that is supporting a $140 million grant program called the Early Literacy Success Initiative to provide districts with money for new curricula and teacher training in reading instruction proven to work for all kids. If districts want the money, they have to present a plan to meet certain standards for what curricula will be used and the methods teachers will be trained in.

But because it’s a voluntary grant program, the quality of a child’s reading instruction in any given district will continue to depend on whether administrators choose to make changes and choose to go after this pot of money. If spending data from the state’s federal COVID relief funding is any indication, many districts could be slow to go after the new state grants.

Oregon’s 197 school districts have been allocated by the federal government about $200 million to spend on combating “unfinished learning” caused by the pandemic. This includes money that could be spent on new reading curricula and teacher training. Districts have through September 2024 to use the money, but some of the state’s largest ones have used only some or none so far, according to an analysis of reimbursements by the Capital Chronicle.

Asked whether continuing to leave decisions about reading instruction in the hands of individual districts perpetuates inequities across the state, Kotek said it wouldn’t, because she expects every one of the state’s 197 school districts to apply for the new funds to improve their reading instruction.

“I think every district is going to come forward with a plan. I mean that. And if they’re not, I’m going to find out why. And we’re going to call them and ask: ‘Why don’t you have a plan? Don’t you want the resources? Don’t you want all your children to have access to these resources?’” she said.

But neither she nor the Legislature will go as far as giving the state Education Department the power to enforce new requirements or mandates on reading curricula and instruction in Oregon. The department recently released updated recommendations for the first time in more than a decade.

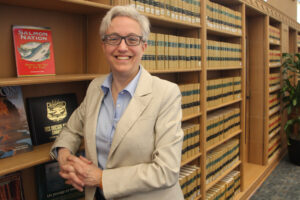

Rob Saxton, a former head of the Oregon Department of Education, said Oregon’s continued reliance on local school boards and the state Legislature to do the work of an education department is part of the problem. He’s supportive of the Early Literacy Success Initiative, which resembles the “Kindergarten Through Grade Three Reading Initiative” he tried to pass in 2015 before it fell to the wayside when former Gov. John Kitzhaber resigned. But, it also continues to leave the quality of children’s education in the hands of elected leaders, not experts, he said.

“The Legislature makes key decisions about education in the state of Oregon — much more so than occurs in some other states, where it’s more like a department of education,” Saxton said. “Everybody always has an idea about how they want to use the money, and it isn’t long before a really good idea becomes so watered down that districts end up being able to use the money for anything that they want to adopt. Pretty soon, more money’s going to districts but nothing happens with literacy.”

At least six states have passed laws outlining requirements for reading curriculum, mostly in the last three years, and 20 have passed laws outlining new requirements related to methods for licensing or retraining teachers in reading, according to an analysis from Education Week.

At the forefront of reading change at the state level is Mississippi, which began about a decade ago to dramatically move away from local control in how reading was taught and teachers trained. Within six years, Mississippi moved from the bottom to middle in the nation in reading proficiency among fourth and eighth graders, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or the “Nation’s Report Card.”

“If you want to accelerate change in public education, you’re going to have to pause local control,” said Kelly Butler, former head of the Barksdale Reading Institute, an advocacy organization that played a key role in implementing change in Mississippi.

Butler said states and their education departments should ensure students receive quality reading instruction proven to work for everyone, especially for students struggling most. The failure to do so perpetuates inequities, according to Butler.

“You’ve got pockets of excellence in the places that know what to do, and the places that don’t, don’t get better,” she said. “If you want a real system of public education that works for everybody, then the things that we know work need to be done everywhere,” she said.

The curriculum that was being used at Brooklyn Primary — Units of Study — is among the most used in the nation, according to a survey by Education Week. But it was not working for everybody, teachers said. Units of Study is based on a theory called “balanced literacy,” in which kids are taught some phonics skills, but are also left to discover the rules of written language independently at their own speed by spending time with good books they’ve chosen.

To use the curriculum, you had to believe kids would learn to read through osmosis, according to Brooklyn teacher Trace Richardson.

“I’m the teacher, you’re the student,” he said, pretending to hand off an invisible book. “‘Here, go off to a cozy corner and learn to read.’ That’s what it was.”

Units of Study involves the teaching of some word-decoding skills, known as phonics, but not enough, experts say. It also involves teaching kids to use pictures and context clues to guess at words which, the experts concluded, is detrimental to teaching kids to read.

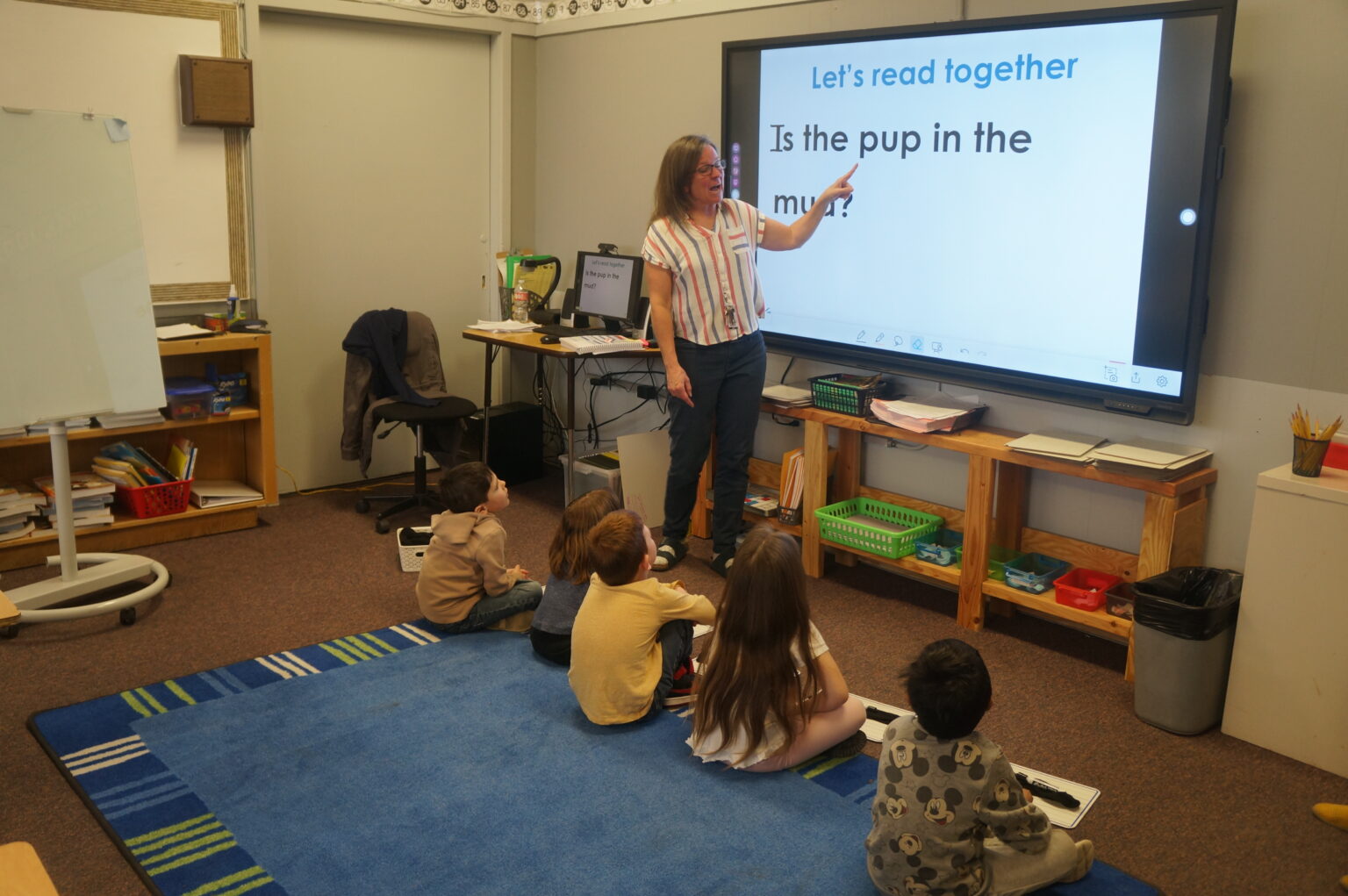

It’s a theory that goes against decades of cognitive and neuroscience research — often referred to as “the science of reading” — that has shown that the human brain does not learn to read or write naturally, but relies on explicit and frequent instruction in a specific set of skills. Everyone needs these skills to read, but learns them at different speeds.

In the fall of 2021, the teachers switched curriculum to one on the state’s approved list. It’s called “Into Reading” published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and is based on teaching according to the reading science. It was not an easy transition for the teachers, who recalled that it focused more heavily on teaching kids rules of written language.

Collier, the principal, brought in Ronda Fritz. Over nine, half-day sessions this spring, Brooklyn teachers watched Fritz, a professor of education at Eastern Oregon University, teach their students to read. Fritz showed them how to use their new curriculum, how to teach kids phonics, to sequence lessons so students were learning words that shared sounds and structures and to build from them. She taught them about the reading science and how to move away from those guessing strategies that had been a part of their teaching before. Fritz has been on a campaign to change reading instruction in districts in Eastern Oregon since she got a doctorate in special education in 2016 and learned, after decades of struggling, how to most effectively teach all kids to read.

Besides showing the teachers how to help kids learn through phonics and word decoding lessons, Fritz taught the teachers principles and rules of written language they had not been exposed to in their teacher colleges, and didn’t know how to explain to kids.

“We never learned the rules,” teacher Ashley Ballard said. “You’re hired and you’re given a boxed curriculum, and they assume you learned how to teach reading in college.”

The Capital Chronicle found many of Oregon’s 15 teacher colleges have only recently begun to change how they instruct future teachers to teach reading, and some are even doubling down on flawed methods.

Kotek recently announced the creation of a new council that will review how reading methods are taught at Oregon’s 15 teacher colleges and recommend updated licensure standards.

Kymyona Burk, former state literacy director for the Mississippi Department of Education, and an architect of the state’s reading overhaul, said changing licensing was what finally got the state’s teacher colleges to change practices.

In 2016, the state required candidates for teacher licensure pass a Foundations of Reading exam, testing them on their understanding of scientifically based reading research and teaching methods.

“Some of our graduates from our premier universities did not make the cut,” she said. “Then we had parents of college students who were calling and saying, ‘My child cannot begin his or her career because they can’t be licensed because they didn’t pass this test.’ ”

This, she said, pressured the colleges to change their instructional methods after years of resistance.

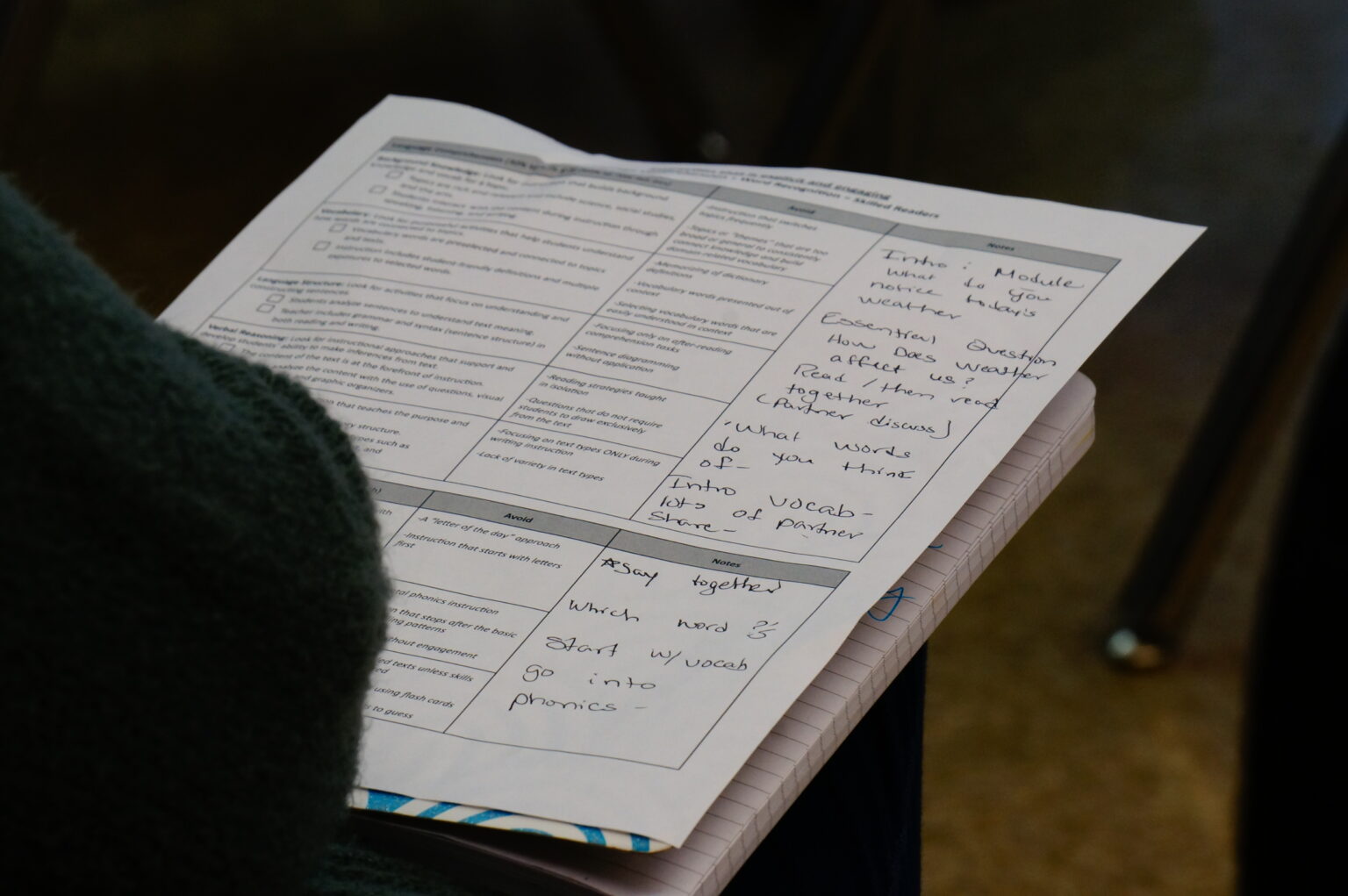

Retraining teachers

In the Klamath County School District in southern Oregon, a change similar to Baker City’s took place this school year. To get teachers trained in the science of reading, Doris Ellison, the district’s new elementary curriculum director, tapped Sasha Borenstein, a special education and reading expert newly hired by Southern Oregon University.

During the summer of 2022, Borenstein trained 49 teachers in the district, including 5 new teachers working at Chiloquin Elementary School, the district’s highest needs elementary school. By this spring, some of the results of the training were paying off. Students at Chiloquin were improving in new assessments taken each month, and some students taught by the new teachers who had been trained by Borenstein were outperforming students taught by veteran teachers who had not taken the training. Some teachers began meeting outside of school to discuss research related to the science of reading and to train one another in Borenstein’s methods.

“It started slow and then it caught fire,” Ellison said.

The district also decided this spring to switch its reading curriculum for the first time in 10 years, choosing one on the state’s approved list, rooted in the science of reading, which teachers will begin using this coming school year.

Borenstein will train 30 more Klamath County teachers this summer, and said she is working with the Southern Oregon Education Service District to retrain teachers in more schools in the region. Fritz, of Eastern Oregon University, has trained teachers in Gresham, Milton-Freewater, Hood River, Harney County and Condon public schools. At least four of the state’s 10 largest districts have offered teachers voluntary training in the science of reading through a program called Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, or LETRS. It was developed by reading expert Louisa Moats two decades ago and is what Mississippi teachers took when the state began to radically transform reading instruction in 2013.

Portland Public Schools has made LETRS training available to teachers since 2020, and more than 600 have taken some or all of it, according to Ryan Vandehey, a district spokesperson. To pay for the training, Portland Public Schools used money from the Student Success Act, a state fund for programs that serve historically underrepresented students, and federal COVID-relief dollars.

Oregon school districts now have more money to invest in teacher retraining and curriculum than ever because of that federal money.

Of the $1.6 billion the Oregon Department of Education and Oregon schools have been allocated since 2020, at least $200 million must be spent by September of 2024 on addressing learning gaps stemming from the pandemic. That means retraining teachers, new curriculum and supplies.

The state education department said Oregon districts have spent twice that amount on unfinished learning already, but according to an analysis of reimbursements among the state’s largest districts, few have spent all or even some of it. The Department of Education has allocated $4 million in federal COVID dollars to improve reading outcomes. It represents about 7% of the $56 million the department received to spend on addressing unfinished learning across the state. That money was used to update the state’s K-12 literacy framework — essentially a set of recommendations for best practices for schools — and to train teachers in reading instruction during the summer as well as funding rural school libraries.

School reports to the state don’t indicate how much districts spent on reading materials and training, but several districts told the Capital Chronicle they used a portion of their federally allocated unfinished-learning money on reading training.

State and federal taxpayers have sent Oregon schools at least $250 million over more than two decades to improve reading instruction. But students have not made major gains, according to state and national assessments.

Gov. Kotek insists that the Early Literacy Success Initiative will have an impact by narrowing the scope of curricula and training districts can use in order to get the money — both will need to reflect the science of reading. She said it will also be different because it also sends money to community-based organizations that will work with families on reading instruction before kids get to kindergarten. She said if the investment is sustained for years, it will be transformative within the lifetimes of the youngest Oregonians.

“If a child is born this year, hopefully they will be benefiting” she said. “Five, six years from now, when that student lands in kindergarten, it’s going to be a different world.”

The architects of change in Mississippi, meanwhile, say that without empowering the state’s education department to set standards for quality reading instruction, and enforce them, change will be slow to come if it does.

Carey Wright, Mississippi’s former state superintendent of education and an architect of the reading transformation there, said change would not have happened if the state’s education department wasn’t given the financial and regulatory power to set standards for reading instruction and enforce them.

A decade ago, when the Mississippi State Legislature passed the Literacy Based Promotion Act and Mississippi began its elementary reading transformation, the Legislature made sure the state’s education department was in charge of change, not the districts.

Each year the department receives about $15 million from the Legislature to provide training in the science of reading to teachers, and to train and place reading coaches in the state’s schools. Districts have never been in charge of the money or decisions.

Wright said that was key. She said she looked at states that had continued to send money to districts hoping they’d make the right choices, and did not want to repeat their mistakes.

“I cannot trust that every superintendent or every principal is going to make a good decision about this. We have got to control for quality, and we have got to control for people that know what they’re talking about,” she said.

Oregon won’t go that far.

“You have to have that balance between local determination and oversight from the state,” Kotek told the Capital Chronicle.

Saxton, the former head of the Oregon Department of Education, said he believes in the initiative and in Kotek’s passion for improving reading outcomes.

“When Tina runs for governor and starts that campaign two and a half years from now, she needs to be able to point to improvements in third grade reading due to this initiative,” he said. But he worries again about a decentralized approach to giving districts the money without strict oversight from the state Education Department and without new requirements to shape how reading is taught.

“I worry about whether or not they will create the requirements that will demand that people actually do precisely with the money what is supposed to happen, and that, that will translate itself into what happens in classrooms,” he said.

Journalist and former Capital Chronicle intern Cole Sinanian contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: Reporter Alex Baumhardt worked almost exclusively on this series for more than four months, starting in January. The project involved extensive research and interviews with more than 80 people, including state and local leaders, teachers, parents and students. She collected data and historical documents through records requests with state agencies and school districts, and visited schools across the state.

Previous reporting:

Part 1: Oregon spends $250 million over 25 years but still fails to teach children to read.

This project was funded by the Urang Schuberth family in the Portland area. The Capital Chronicle was rigorous in maintaining a firewall between the project and the funders. States Newsroom, the nonprofit 501c(3) organization based in North Carolina that created and funds the Capital Chronicle, oversaw the project funding.

Oregon Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oregon Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Lynne Terry for questions: [email protected]. Follow Oregon Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)