Opt Out at Florida’s Supreme Court: How a Fight Over a Third-Grade Test Is Pitting Parents vs. the State

After earning A’s and B’s on her report card last year, Michelle Rhea’s daughter was looking forward to entering fourth grade at Dommerich Elementary School in Orange County, Florida, where she would play in the band and be part of the after-school safety patrol.

But two weeks before the 2015–16 school year ended, Rhea was told her daughter would not be promoted because she had opted out of the state exam that third-graders must take to prove competency in reading.

“As a parent, I was sitting there, going, ‘So why did I send her to school for 180 days?’ ” Rhea said.

Rhea is one of a dozen parent plaintiffs challenging Florida’s use of the test to determine whether third-graders should be promoted. This month, they appealed a ruling against them in Florida Supreme Court.

The parents first sued the state Department of Education and the school boards of seven districts last August, charging that Florida school systems hold back third-graders who don’t have reading problems, simply because they don’t believe in taking the state’s standardized test to prove it.

“It doesn’t matter if you had a bad day or you are not good test taker,” said Cindy Hamilton, co-founder of Opt Out Florida Network, a coalition of activist groups. “If you don’t pass a test, you don’t go to fourth grade.”

The network organized the parents last summer and is orchestrating a fundraising campaign to pay their legal bills.

Under state law, third-graders must score a Level 2 or higher on the English Language Arts section of the Florida Standards Assessments (FSA) in order to be promoted to fourth grade. Districts can exempt third-graders from mandatory retention for “good cause” if they present a portfolio of work that demonstrates acceptable reading skills.

Then-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush signed the law that took effect in 2002 as part of a push for greater test-based school accountability, arguing that students who don’t learn to read by third grade struggle in other subjects later on.

“Florida’s students have made significant strides since the inception of the state’s accountability system, and we have a duty to maintain its integrity,” Education Commissioner Pam Stewart said in a March statement. “We are committed to making Florida the best place in the world to receive an education, and we will continue advocating for our state’s students.”

Proponents of Florida’s retention rules argue that third grade is a pivotal year, when students are expected to be reading to learn instead of learning to read. Kids who still struggle with reading in third grade suffer academically throughout their school careers.

“Students retained under Florida’s test-based promotion policy perform at higher levels than their promoted peers in both reading and math for several years after repeating third grade,” Martin West, an associate education professor at Harvard University, wrote in an analysis for the Brookings Institution.

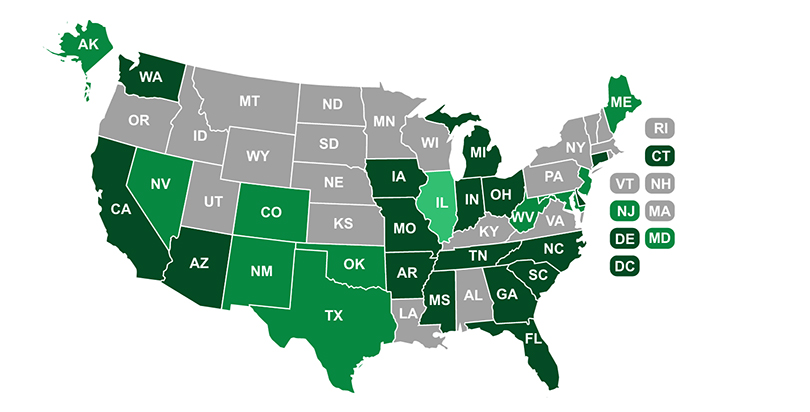

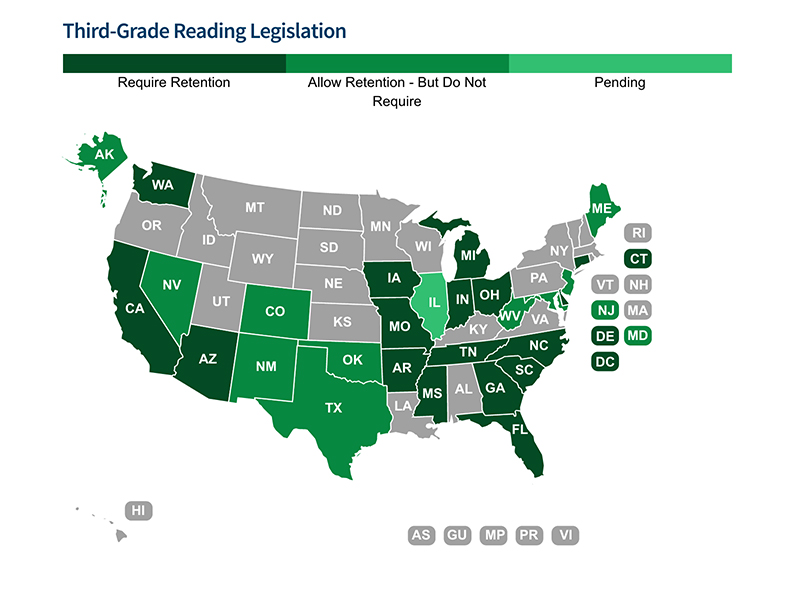

Some 15 states and the District of Columbia have passed similar laws, but many have also faced pushback from some parents, researchers, and activists who worry that kids may be hurt in the long run. Some critics argue that the evidence on the effectiveness of retaining struggling readers is too contradictory and that providing an extra year of schooling is too costly for districts.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/third-grade-reading-legislation.aspx

As the national opt-out movement persisted last year, some Florida parents, including the plaintiffs, told their children to “minimally participate” in the exams by writing down their names but not answering any questions.

The plaintiffs had planned on using portfolios to prove that their children’s reading was up to par but were notified last spring that their kids would be held back.

Their lawsuit contends that districts have been inconsistent in awarding “good cause” exemptions because the state failed to offer clear guidance in a timely manner. Some districts allow kids who opt out of the state exam to be promoted if they take another assessment such as the Iowa test, while others use classroom observations or report cards.

Leon County Judge Karen Gievers agreed with the plaintiffs. In an August ruling, Gievers said the districts should have notified their parents of their children’s reading deficiency right after the test, and then implemented a remediation plan.

But in March, a three-judge appeals panel overruled Gievers, saying Florida has a “compelling reason” to identify and hold back students with reading deficiencies, and to have all students take the test so the state will continue to receive federal aid. The court also said the cases needed to be brought in the individual counties where the school districts were located.

On April 5, the parents appealed to the Florida Supreme Court.

Rhea, like some other parent plaintiffs, put her daughter in a private Montessori school for fourth grade while the lawsuit was being litigated. She hopes her daughter can return to Dommerich Elementary School for fifth grade in the fall.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)